Revitalizing campus spaces

Indigenous language on campus

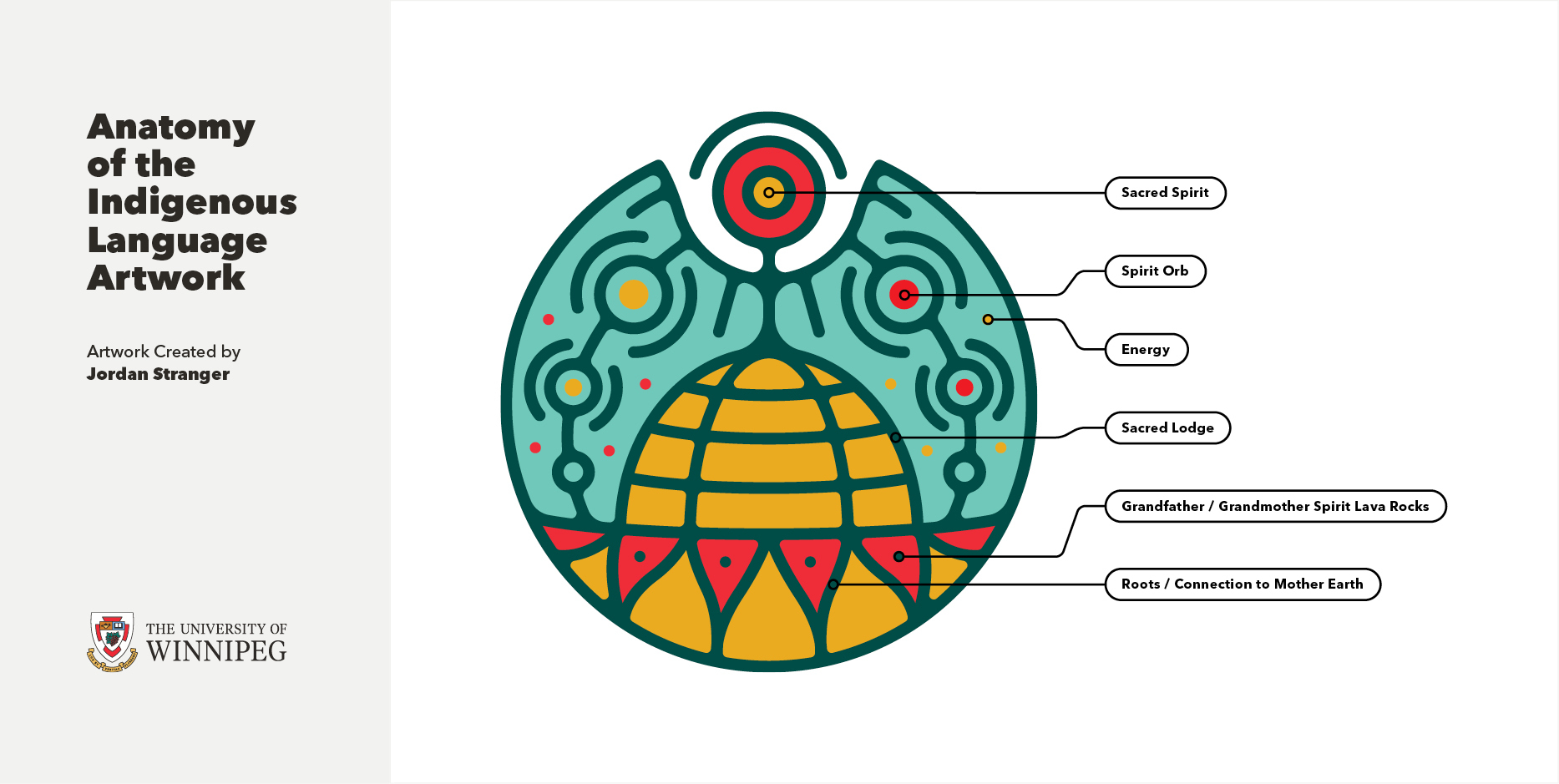

Indigenous language artwork

The language banners that welcome you as you enter Centennial hall are decorated with artwork by Jordan Stranger an Oji-Cree individual originally from Peguis First Nation. His art is also diplayed on the top of this page. It represents the importance of preserving Indigenous languages and celebrating Indigenous culture on campus.

If you look closely, you will see a Sacred Spirit joined in arms with ancient spirits (otherwise known as Spirit Orbs.)

They are all connected to a sacred lodge – a safe space to conduct ceremonies and other gatherings.

Below them in the soil and roots are ancient stones (Lava Rock) full of energy which hold up the lodge with the help of Mother Earth.

Together they are all connected and rooted in place, ready for whatever comes.

(Click image to enlarge)

Welcome banners in Centennial Hall

As you ride the escalators in Centennial, you will notice Indigenous language banners welcoming you to campus. These banners represent the importance of language revitalization and inclusion, greeting visitors to the university in 11 languages (including English).

Join us in saying “tawâw, iyuskin, iindigen, wotziye, tunngasugit, pee-piihtikweek, bonjour, waaciye, tánsi, kuwa, and welcome” to all visitors, students, faculty, and staff who connect, work, and study on campus.

- Ta wâw means “you are welcome, there is room” in the Cree language.

- Iyuskin means welcome in the Dakota language.

- Biindigen means “come in” in the Ojibwe language.

- Wotziye means “hello” in the Dene language.

- Tunngasugit means “welcome” in the Inuktut language.

- Pee-piihtikweek means “welcome, or come in” in the Michif language.

- Bonjour means “hello” in the French language.

- Waaciye means welcome in the Oji-Cree language

- Tánsi means welcome in the Cree language.

- Kuwa means welcome in the Dakota language.

These translations have been guided by UWinnipeg community partner, Indigenous Languages of Manitoba, a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring the strength and survival of our Indigenous languages.

Artwork inspired by ancient Indigenous medicine wheel

As you enter Axworthy Health and RecPlex, you will be welcomed by a wall etching representing the coming together of people in reconciliation, healing, and wellness.

ASIN (meaning stone in Ojibwe) is a collaborative public artwork between Ebb and Flow First Nation, UWinnipeg, and artist-architect Eduardo Aquino.

ASIN represents the encounter of Indigenous and settler cultures, promoting the dialogue and the common growth within a shared territory.

The pattern was inspired by and based on a topographical map of the only ancient Medicine Wheel in the province of Manitoba, which is located on the historical lands of Ebb and Flow First Nation, near Alonsa. The medicine wheel is frequently associated with ceremony, cleansing and healing of the body and spirit, and regeneration of the earth and its resources.

The poem depicted on this artwork was composed by members of Ebb and Flow First Nation, and speakers of the Memekwesiak, (or ‘little people’). According to members of the community, the Memekwesiak exist in both the material and spirit worlds and the Medicine Rock, also located in the community of Ebb and Flow, is thought to be a gateway between these realms. Traditionally, visitors to the Medicine Rock leave tobacco, food and cloth as gifts to the Memekwesiak. The text was blessed by Ebb & Flow Elders, Percy and Mary Houle, and was translated into Ojibwe by Olga Houle.