Reading This Place

One Book UWinnipeg

During the Fall term, students in Dr. Candida Rifkind's Honours/M.A. Seminar on Indigenous comics were invited to post brief reflections on one story from This Place: 150 Years Retold.

Contents

Sarah Martin, "Colour, Lines, and Story: The Emotional Effect of 'Tilted Ground'"

Ciarra O'Reggio, "Survivance in the Green: Colour Symbolism in 'Tilted Ground'"

Kim Thien Cao, "Examining Dissonance in 'Red Clouds' by Jen Storm"

Kamal Dhillon, "The Windigo as Colonial Agent in 'Red Clouds'"

Wencke Rudi, "The Haunting of 'Red Clouds'"

Andrew Brown, "Birch Trees and Double Standards in 'Peggy'"

Blake Carter, "Faded History: Representations of Indigenous War Veterans in 'Peggy'"

Sophia Hershfield, "'We Will Keep Fighting:' A First Nation War Story in 'Peggy'"

Sabrina Zacharias, "'Peggy': Engaging with Indigenous Identity and Culture through Colour"

Rhys Delios, "'Let's Stick with Rosie': Names and Inuit Secrets in 'Rosie'"

Kell Hagerman, "The Thunderbird as a Symbol of Resistance and Resilience in 'Nimkii'"

Alexander Lucy, "'Warrior Nation': A Love Story"

Colour, Lines, and Story: The Emotional Effect of "Tilted Ground"

Sarah Martin, MA in Cultural Studies

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Martin, Sarah. “Colour, Lines, and Story: The Emotional Effect of ‘Tilted Ground’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

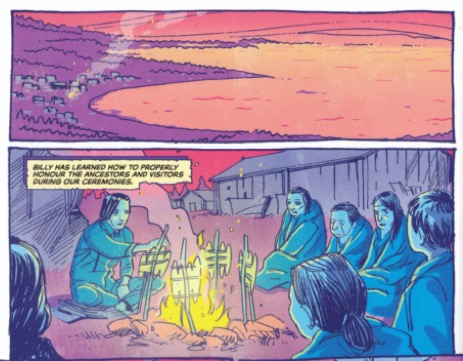

“Tilted Ground” is a 2018 comic included in the Indigenous comics anthology This Place: 150 Years Retold. Written by Sonny Assu, illustrated by Kyle Charles, and coloured by Scott A. Ford, it tells the story of Sonny Assu’s great-great-grandfather, Chief Billy Assu, and how he maintained Kwakwaka’wakw practices and the language while they were banned by the Canadian government from 1885 until 1951 (Assu, “Tilted Ground” 28-29). Contrasting colours, gritty lines, and the author’s personal connection come together and create a moving historical narrative.

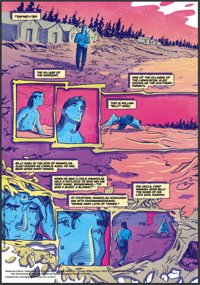

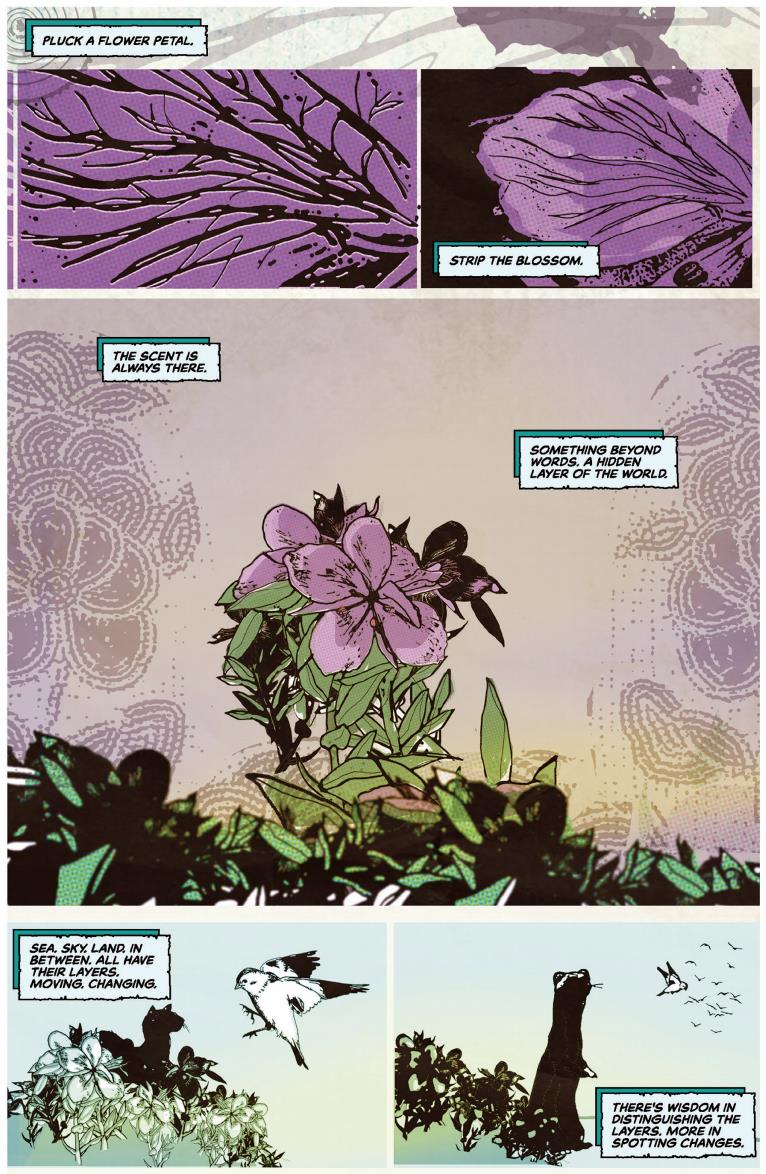

The title page introduces the rich sunset colour palette that dominates the majority of the comic. Purple, lavender, pink, gold and peach give a warm and inviting tone to the backgrounds of each panel within an “Indigenous setting” where the forests, coast, reserve land and water are all coloured in this palette.

Fig. 1 Billy Sharing the Origins of His People: Page 34 of Sonny Assu’s “Tilted Ground”.

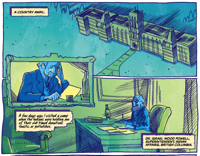

The few panels located in settler spaces contrast the sunset color scheme. The British Columbia legislature, John A. MacDonald’s office, Parliament, and sociologist Franz Boas’ office are coloured with in a cold green background. The gold of fire or the red and orange of the sun are lost completely in these panels. The uncomfortable discord between the colours of these panels reflects the injustice they depict.

Fig. 2 Parliament’s Evaluation: Page 36 of Sonny Assu’s “Tilted Ground”.

Colour also dictates tone, as opposed to the ambiguity of black and white comics. In an interview earlier this year, Portage and Main Press shared an uncoloured sample of “Tilted Ground” in advance of This Place’s publication that demonstrates this nicely. There is a stark difference between the coloured and uncoloured drawings—the tone in the finished version is far less ambiguous between and within panels.

Fig. 3 Portage and Main Sample Uncoloured: TILTED_GROUND_THISPLACERETOLD2019

Fig. 4 Final Coloured Version of Portage and Main Sample: Page 37 of Sonny Assu’s "Tilted Ground."

Normally, I prefer to read comics in black and white, since colour feels much like when someone reads to me a book out loud—they are controlling the ambiguous parts of meaning within the story, the tone in the narrative, and usually I disagree with it. I find that my own interpretations differ and fight against what is being dictated by the colouring. But this story is one where I appreciate that direction. The colouring guides how I interpret the image and indicates very obviously whether a place is colonial or Indigenous.

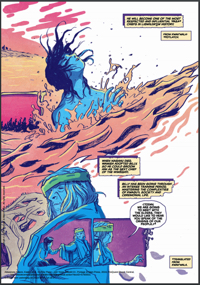

The ratty-lines of both the panels and the drawings in “Tilted Ground” are the next aspect that draw the eye and express emotion. The best and most elaborate example is the first two-page spread introducing the main character, Billy Assu.

Figs. 5 & 6 This is Billy Assu: Pages 32-33 of Sonny Assu’s “Tilted Ground”

Instead of the standard comics grid, Billy Assu and his uncle Chief Wamish are introduced through a montage of flowing images combining river and tree limbs. These images flow together, creating one fluid image than the overlap of several, conveying the feeling that the two characters are part of one whole—the current Chief, looking out at and guiding the future one.

Even though the majority of “Tilted Ground” isn’t illustrated in this grid-less format, the more typical panels are no less irregular in form. The lines of the panels and the spaces of the gutter are wavy, and the use of dark purple instead of black for the lines make the white of the gutter less severe. This unevenness feels like a continuation of the tree branches from the first pages, which combined with the beauty of the rest of the drawings of people and places is eye-catching.

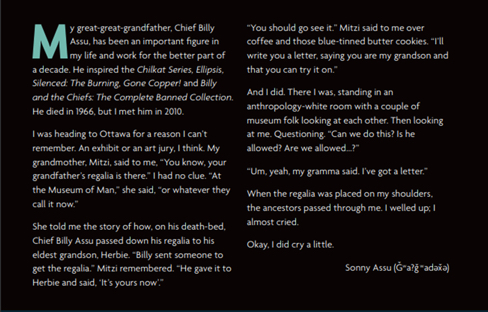

Sonny Assu’s personal connection to Billy Assu is the last part of “Tilted Ground” that resonates emotionally. He explains his connection in the introduction (see Fig. 7 below).

Fig. 7 Sonny Assu Introduction: Page 28 of Sonny Assu’s “Tilted Ground”.

The obvious importance of Assu’s ancestry and his connection to it are the spirit that animate the colours and lines of “Tilted Ground” and make it a touching comic. There is power in remembering our ancestors and sharing their stories. It’s inspiring to read about the persevering nature of Billy Assu—how he finds work for his people, negotiates wages and fair prices, devises means to keep the village children from Residential Schools, and succeeds in “adopting” settler ways without assimilating them (Assu, “Tilted Ground” 48). Combined with rich colours and organic linework, the story of Sonny Assu’s great-great grandfather comes to life.

Works Cited

Assu, Sonny. “Tilted Ground.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. 28-53.

"Honouring the Indigenous Tradition of Potlatch." Portage & Main Press. Jan 24, 2019. Web. Oct 10, 2019 <http://www.portageandmainpress.com/blog/2019/01/24/honouring-the-indigenous-tradition-of-potlatch/>.

back to top

A Preservation Pedagogy in Practice: Approaches to Language Preservation in "Tilted Ground"

Alexandra Neufeldt, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Neufeldt, Alexandra. “A Preservation Pedagogy in Practice: Approaches to Language Preservation in “Tilted Ground.” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

“Tilted Ground” by Sonny Assu, Kyle Charles, and Scott A. Ford, tells an anti-hegemonic history and is itself an attempt at preserving culturally and historically significant texts. As the comic tells the story of how Assu’s great- great-grandfather, Billy Assu, preserved the potlatch when the Canadian government tried to ban it, Sonny Assu, Charles, and Ford preserve the language(s) that took part in the story. The comic is guided by several philosophies of language preservation, including Kwak’wala, state language, and academic language. These are a key part of the storytelling and tie in thematically to the story of Billy Assu, but they also teach how to treat different kinds of sources when telling an anti-hegemonic history.

Assu uses two different techniques to signal that characters are speaking Kwak’wala, the language of T’sakwa’lutan: untranslated Kwak’wala with an asterisk and translation at the bottom of a panel, and chevron brackets (< and >). Page 33 uses both techniques: at the top right corner and bottom right corner of the page (panels 1,3.33). Different words require different translation treatments to tell this story properly.

Fig. 1 & 2 Two Ways to Translate: Excerpts from page 33 of Assu, Assu, Charles, and Ford’s “Tilted Ground.”

- Most of the translated chevron-bracketed dialogue happens when most of the people present are fluent in the same language. Culturally important words or words without a relatively clear translation to English remain in chevron-bracketed text with rough translations in narratorial boxes. This prevents the translated Kwak’wala from fading into the translation.

- When representatives of the Canadian government are present, Kwak’wala with an asterisk and bottom translation allows the Kwagu’ł people to hide their plans, truths, and intentions in plain sight, just as they later do with the potlatch (3.41-5.42). Kwak’wala is not just something to be saved in secret, it is an active tool of resistance.

Fig. 3 Hiding in Plain Sight: Excerpt from page 41 of Assu, Charles, and Ford’s “Tilted Ground.”

Alongside the preservation of Kwak’wala, Assu preserves the words of settlers, quoting extensively from Government of Canada Documents and anthropologist Franz Boas’ work, to very different effects.

- The transition between Assu’s words and the Canadian government’s, all neatly cited at the end of This Place, holds these figures accountable for their genocidal words and actions.

- This technique also highlights these settler figures’ removal from T’sakwa’lutan through their removal from Assu’s writing. Though Powell is geographically close, he is still “a country away” from T’sakwa’lutan and very out of touch with their laws (1.36).

- Powell’s words to Macdonald may be in a similar narrative box to Assu’s narration, but they do not have the same lettering style (2.36). Assu’s narrative boxes coexist in the same panel, subtly asserting dominance over the parallel narration, establishing Powell’s as secondary and non-authoritative (2.36).

- This representation of settler state removal from T’sakwa’lutan is not only present in the use of citations, but also in the colour schemes. The scenes in government buildings are in sickly greens, in opposition to the rosy pinks and purples of T’sakwa’lutan (see 1,2.36 compared to 3,4.36).

Fig 4. “A Country Away:” Excerpt from page 36 of Assu, Charles, and Ford’s “Tilted Ground.”

The inclusion of Franz Boas’ work in Tilted Ground is a somewhat surprising decision given the well-documented tendency towards anti-Indigeneity in anthropology. However, his words are also used in one of the most important sequences of Tilted Ground, Wamish’s speech to Boas (42-45).

- In the sequence from pages 44 to 45, the words of the Wamish are chevron bracketed, indicating Kwak’wala as the dominant language for this sequence and only Boas is not fluent in Kwak’wala. However, everything Wamish is saying is quoted from Boas’ account of his visit, as interpreted by George Hunt (2.42).

- Compared to Assu’s narration and speech balloons, the lack of Kwak’wala words in Wamish’s speech is noticeable. Sonny Assu’s approach to the story of the preservation of the potlatch seems to be to preserve as much as possible, and with this powerful and well-known speech, he uses the only text available.

In “Tilted Ground,” the placement and style of narrative boxes, speech balloons, and translation notes are just as useful for recontextualizing the words of the oppressor and giving Indigenous voices – whether in Kwak’wala or English – priority and control as iconography can be in other comics.

Bibliography

Assu, Sonny et al. “Tilted Ground.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. pp. 28-50.

Carrol, Jane. “Invisible Partners: Recovering Relationships in Early Anthropological Research.” Omnia, Penn State Arts and Sciences, 13 September 2018. https://omnia.sas.upenn.edu/story/invisible-partners-recovering-relationships-early-anthropological-research

Elliot et al. This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. pp. 28-50.

Pels, Peter. “The Anthropology of Colonialism: Culture, History, and the Emergence of Western Governmentality.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 26, 1997, pp. 163–183.

Todd, Zoe. “What does it mean to decolonize anthropology in Canada?,” Savage Minds, 17 August 2016. https://savageminds.org/2016/08/17/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-anthropology-in-canada/

back to top

Survivance in the Green: Colour Symbolism in "Tilted Ground"

Ciarra O'Reggio, BA in English

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

O’Reggio, Ciarra. “Survivance in the Green: Colour Symbolism in "Tilted Ground. "One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

The story of "Tilted Ground" follows Sonny Assu's great-great-grandfather, Billy Assu, as he leads his community of T'Sakwa'Lutan through the era of the Potlach Ban in the early 1900s. Though the community faces challenges due to colonial interference, Billy Assu and the rest of the Wiweqayi are able to continue having potlaches even larger and more elaborate than before. Supplemented by Kyle Charles’s effortless gestural illustrations and Scott A. Ford's limited colour palette, the story of "Tilted Ground" becomes a vibrant comic that stands out in This Place: 150 Years Retold. Ford imbues colours with certain affective qualities and cultural affiliations to help tell a story of attempted assimilation and enduring Indigeneity. In this way, colour becomes an affective tool in conveying a story of Indigenous survivance. "Survivance" stories (a term coined by Gerald Vizenor) are "renunciations of dominance, tragedy, and victimry" ("Acts of Survivance") – they tell a story of active Indigenous presence, rather than a story of defeat.

Fig. 1 T'Sakwa'Lutan colour scheme: Excerpt from page 34 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

Early in the comic, Assu, Ford, and Charles establish two dominant colour schemes that illustrate a belonging (or unbelonging) to the land. In one colour scheme (Fig. 1), the Wiweqayi are so inseparable from the land that their violet houses blend easily into magenta sky, purple earth, and treeline. The relaxed, gestural figures congregated around a warm yellow fire create a feeling of warmth and comfort.

Fig. 2 Parliament Hill colour scheme: Excerpt from page 36 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

In contrast, Parliament Hill is green and turquoise, and it stands on a prim and proper, empty lawn. The looming rectangular building casts a long hashmarked shadow behind it. This sequence clearly takes place elsewhere, as the cool greens contrast starkly with the warm colour palette that was established in T'Sakwa'Lutan. The third panel in the sequence may also resemble the colour and composition of a Canadian twenty dollar bill, which suggests material wealth as well as colonial influence.

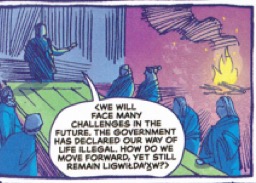

Fig. 3 Wiweqayi deciding their future: Excerpt from page 46 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

After his uncle dies and Billy Assu becomes Chief, he decides to take T'Sakwa'Lutan in a new direction. The yellow fire, which represents the livelihood of Ligwilda'xw tradition and culture, still burns in the background, but instead of congregating around the fire, the Wiweqayi now sit at a green table as they decide their future. In order to survive as a community, they must face the colonial powers attempting to destroy the Ligwilda'xw way of life by dealing with settlers on a level playing ground, hence the green table.

Fig. 4 More Elaborate 'Pasa: Excerpt from page 49 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

The Wiweqayi face many challenges as they adapt to the new European influences in T'Sakwa'Lutan. But, through their communal resistance, the community uses the influx of colonial goods, industry, and wealth "to hold even larger and more elaborate 'Pasa" (Assu et al. 49). Given that Assu, Ford, and Charles have imbued green with associations of colonial power, to see the Wiweqayi using green objects to continue their traditions is ironic; Chief Assu upholds T'Sakwa'Lutan's traditional Ligwilda'xw ways by manipulating the very forces that try to extinguish their culture.

The conclusion of "Tilted Ground" ends the comic how it began:

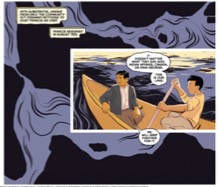

Fig. 5 Billy Assu introduced: Excerpt from page 32 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

Fig. 6 Billy Assu swimming: Excerpt from page 52 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

In both sequences, Billy Assu takes an early morning swim, but on the last page, it is amidst a green boat which represents the changes that have reshaped T'Sakwa'Lutan. Still, Assu, Ford, and Charles reinforce that the land remains the same, and the Wiweqayi remain integral to said land. In a defeatist narrative, the colour scheme of T'Sakwa'Lutan may have complete turned green by the last page, but in "Tilted Ground" the colour scheme is made up of the same sunset hues till the end.

Fig. 7 Billy Assu's child: Excerpt from page 52 of Assu et al. "Tilted Ground."

Or should I say, not the end. The final panel is a close up of Billy Assu's child. The child is swaddled in green, representing the emergence of a new generation who, though influenced by European culture, are still supported by the generations of ancestral tradition and resistance that came before them. Choosing to close the comic with "Not the end" ties the comic together as a story of Indigenous permanence and survivance.

Altogether, the symbolic rather than representative colour palette in "Tilted Ground" deconstructs colonial narratives and, like so many other chapters in This Place: 150 Years Retold, "Tilted Ground" paints a picture of Indigenous survivance, one that exemplifies the power that visual storytelling can wield.

Works Cited

Assu, Sonny et al.. "Tilted Ground." This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. pp. 28 - 52.

"Acts of Survivance." Survivance, 20 Apr. 2016, http://survivance.org/acts-of-survivance/.

back to top

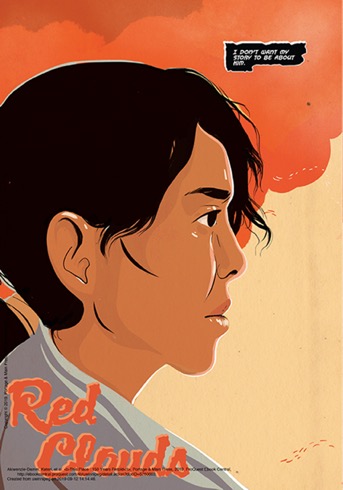

Examining Dissonance in “Red Clouds” by Jen Storm

Report by Kim Thien Cao, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Cao, Kim. “Examining Dissonance in ‘Red Cloud’ by Jen Storm.” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

Overview

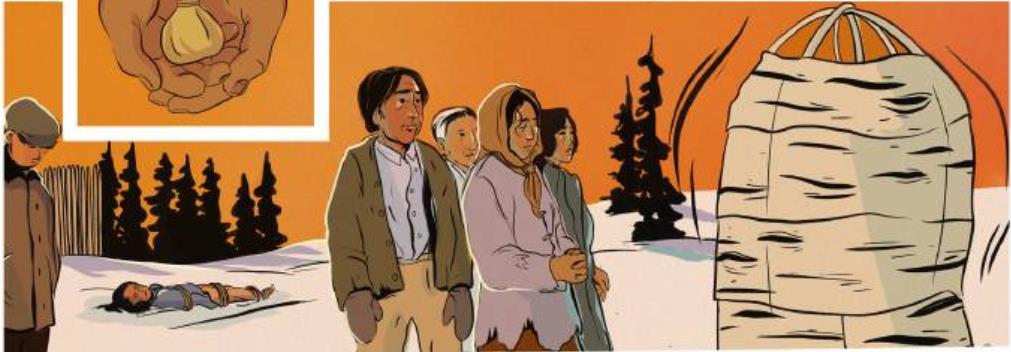

In This Place: 150 Years Retold, “Red Clouds” by Jen Storm recounts the historical incident of Jack Fiddler’s arrest in 1906 for killing fourteen people in Sucker First Nations. The story reflects the injustices and changes Indigenous communities faced during the 20th century, when northwestern Ontario not only faced starvation but, also how a “way of life […that] changed forever” (Storm 54).

Artist’s Talk

In an interview for Portage & Main Press/Highwater Press, Storm talks about the perspective of the character Wahsakapeequay while weaving in the oral stories of the Wendigo. She also stresses the importance of centering the narrative through the lens of a woman’s perspective “without retelling the one already written” (54).

Observations & Reflections

I will closely examine how colonial violence effects Indigenous perspectives, communities and laws. A few highlighted scenes from Storm’s comic, personal observations, and reflection can be found below.

Contrasting Ideas/Imagery

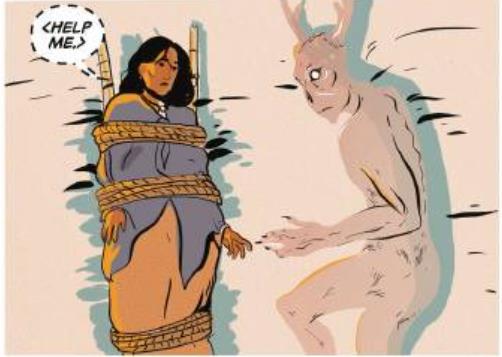

- Wahsakapeequay is tied up and pleas, “help me” (68) to the Wendigo spirit.

Observations:

- There is a tender interaction that closely resembles Michaelangelo’s Creation of Adam where they lie side by side with their fingers almost touching. The images show a quiet understanding between Wahsakapeequay and the Wendigo.

- However, the community is shown with their backs turned to her to reflect the distance and rejection Wahsakapeequay experiences as a result of colonial violence.

Community

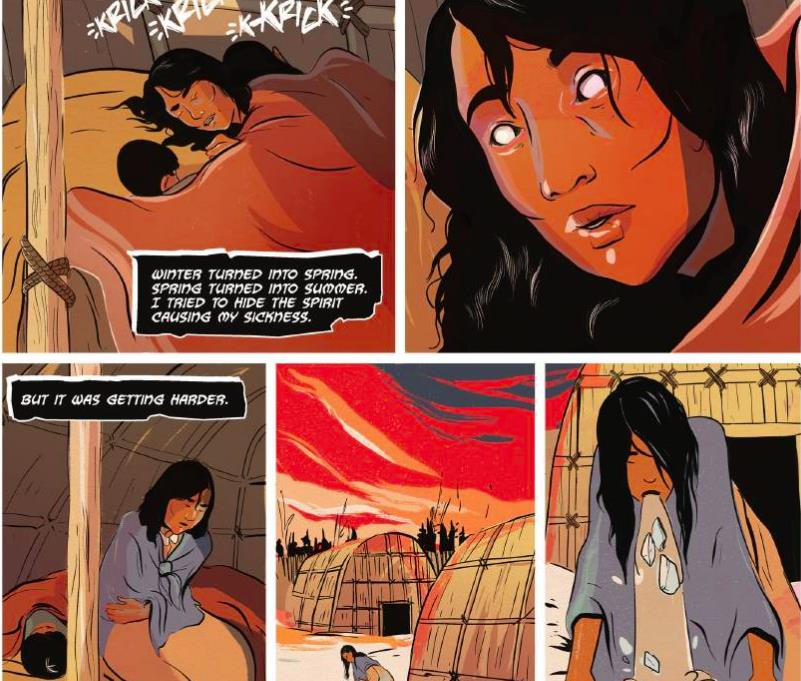

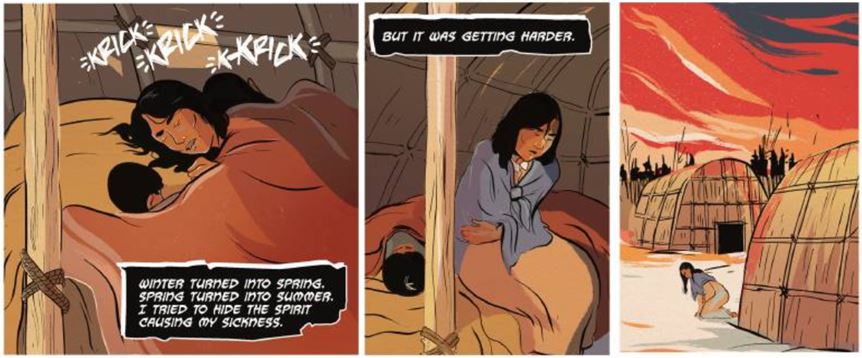

- Wahsakapeequay “tried to hide the spirit causing [her] sickness” (65, panel 1) but eventually, she is forced to leave the shelter to purge (65, panel 3-5).

Observations:

- Due to her unresolved trauma and illness, Wahsakapeequay exists outside the idea of what/who belongs, and is also shown at times on the cusp between two shelters/communities, the Indigenous and the colonial) (65, panel 4).

- The tension and disconnection highlights how much healing is needed in the community.

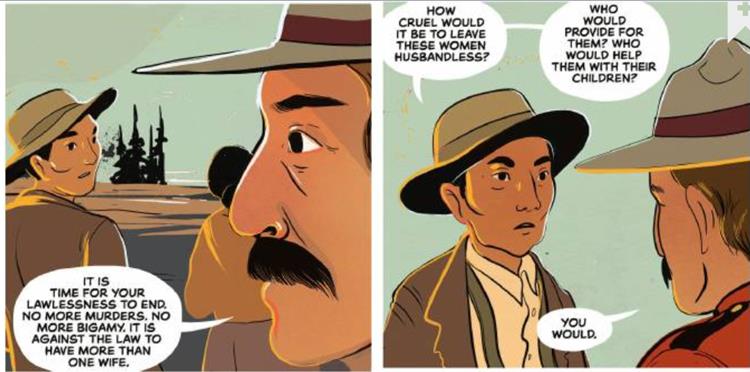

Law

- Joseph Fiddler asks, “how is a ‘death sentence’ different from what we did?” (78, panel 9).

Observations:

- Fiddler critiques the hypocrisy of how the root cause of the Sucker people’s lateral violence is due to in an attempt to eradicate the ‘Indian problem’.

- Thus, the white man’s law is used as a topical ‘heroic fix’ to erase Indigenous sovereignty and ways of living.

Reflection

Ultimately, Storm offers a way to look at the Wendigo beyond the colonized narrative of the villainous ‘evil spirit’. Instead, “Red Clouds” allows space for a re-imagining of Sucker peoples’ history from an Indigenous writer’s perspective. The comic creates tension between Indigenous and colonial perspectives through the tale of the Wendigo. For instance, in Haudenosaunee confederacy, the Great Binding Law states, “all my relations […] we are all connected” (Bineshiikwe 1), which emphasizes how everything in life is essential in maintaining balance. Spirits like the Trickster or the Wendigo are part of creation, and should be respected for their teachings rather than a spirit that is disregarded. However, because Wahsakapeequay was not given that opportunity to heal, the Wendigo spirit feasted on her trauma and consumed her. As a result, the Wendigo appears as an allegorical ghost; it hovers on the pages and through the experiences of the characters but is not able to yet be held by the community. Overall, colonial laws and judicial systems are complicit in the creation of policies that work to eradicate Indigenous communities like the Sucker nation. Until the ‘white man’s laws’ are removed from Indigenous communities, the violence will only continue to feed and transform the Wendigo.

Works Cited

“Biography – ZHAUWUNO-GEEZHIGO-GAUBOW – Volume XIII (1901-1910) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Home – Dictionary of Canadian Biography, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/zhauwuno_geezhigo_gaubow_13E.html.

“Confederacy's Creation.” Haudenosaunee Confederacy, 23 Jan. 2019, https://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/confederacys-creation/.

“HighWater Press.” Portage & Main Press, 6 Feb. 2017, https://www.portageandmainpress.com/highwater-press/.

Hopper, Tristin. “Here Is What Sir John A. Macdonald Did to Indigenous People.” National Post, 28 Aug. 2018, https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/here-is-what-sir-john-a-macdonald-did-to-indigenous-people.

“Jen Storm on Windigos and a Way of Life That Changed Forever .” Portage & Main Press / Highwater Press - The Exchange, 24 June 2019, http://www.portageandmainpress.com/blog/2019/06/24/jenstorm-redclouds-thisplaceretold/.

“Michelangelo's Creation of Adam.” ItalianRenaissance.org, http://www.italianrenaissance.org/michelangelo-creation-of-adam/.

Portage & Main Press/ HighWater Press. YouTube, YouTube, 16 Jan. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_bCzsaqpuys.

“This Place.” Portage & Main Press, 21 Oct. 2019, https://www.portageandmainpress.com/product/this-place/.

“Windigo.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/windigo.

back to top

The Windigo as Colonial Agent in “Red Clouds”

Textual analysis by Kamal Dhillon, MA in Cultural Studies

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Dhillon, Kamal. “The Windigo as Colonial Agent in ‘Red Clouds’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

Overview

“Red Clouds” is a story written by Jen Storm and illustrated and coloured by Natasha Donovan in the comics anthology This Place: 150 Years Retold. The story is an allegory that reveals how a system of colonial rule controls the land and its resources, destabilizes communities, and establishes systems of law, not justice. In this context, the cannibalistic windigo monster symbolically transforms into a colonial agent.

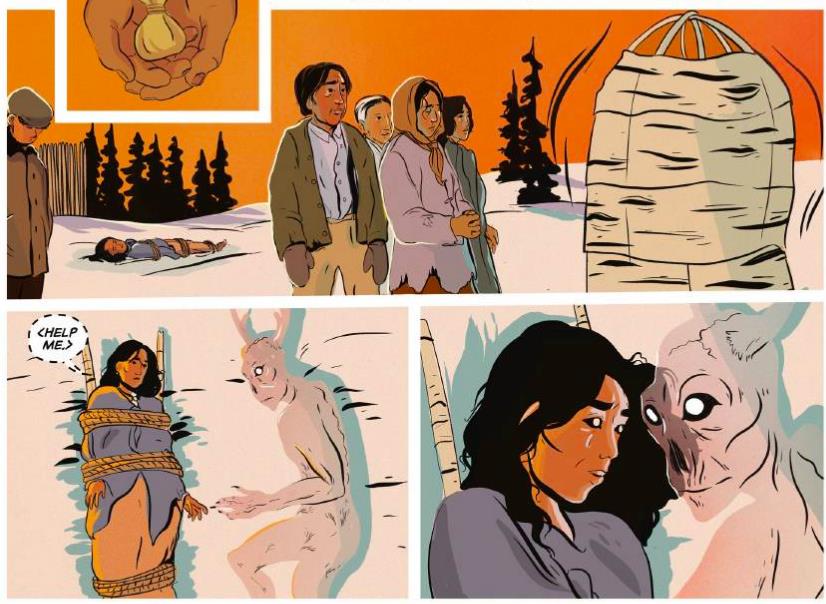

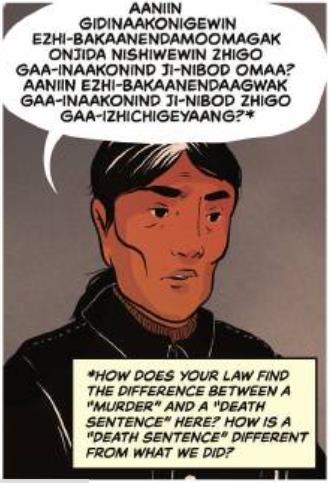

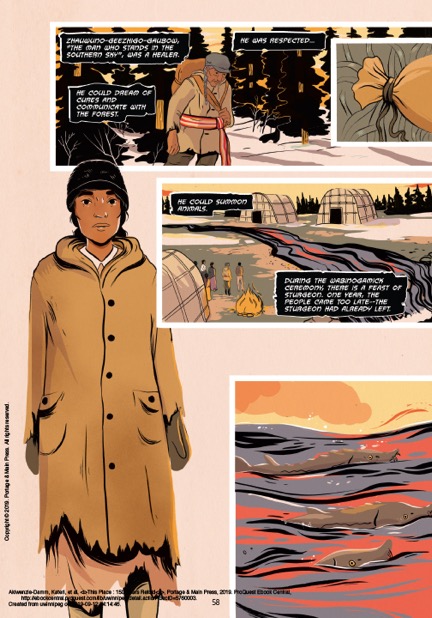

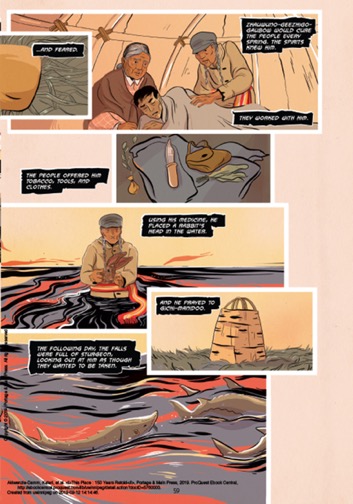

Colonial starvation: feeling the effects of the fur trade era

The first sighting of the windigo occurs in the depths of winter, as hunger rages and colonial expansion threatens to continue to clear the land of its animals. The end of the fur trade era put entire communities at risk.

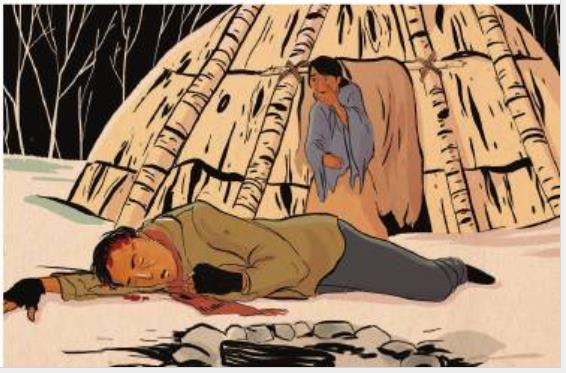

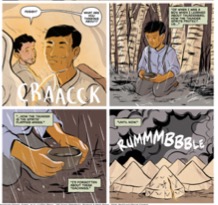

Wahsakapeequay, the story’s narrator, has left her community in search of food. As her family faces the brink of starvation, Wahsakapeequay’s husband leaves to try his luck at hunting; ironically, he returns as wounded prey (Fig 1).

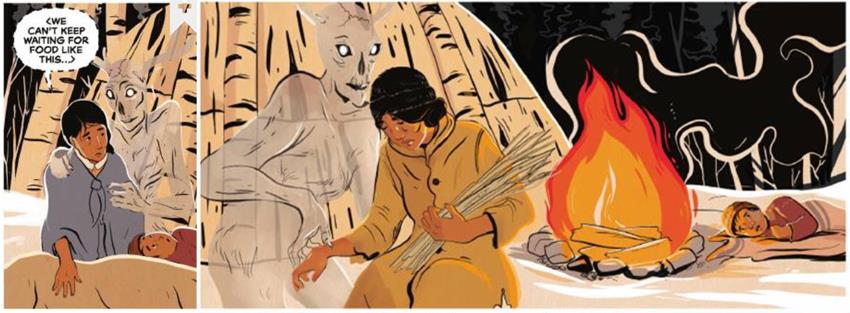

Windigo picks up on the scent of blood and approaches Wahsakapeequay’s camp. Unbothered by the cold, the monster pretends to be concerned for Wahsakapeequay’s situation (Fig 2). This is a trick – he intends to colonize her mind but needs her to believe it is for her own well-being.

Wahsakapeequay’s son can see Windigo, and the seduction that is taking place, which is clear from his facial expressions. He witnesses his mother relinquish control and succumb to cannibalism (Fig 3).

However, it is not Wahsakapeequay’s greed that invites Windigo, it is the settler-imposed land hunger which gives birth to the monstrosity.

Colonial isolation: breaking down individuals and weakening communities

Wahsakapeequay understands the healing power of community, and so decides to return to “(her) people” for a chance at life for her and her son (64).

The windigo does not like that she has returned, because it gains its power through alienating individuals from their communities. It pushes back against its host, destabilizing her inner equilibrium, and causes her to be physically ill (Fig 4, 5 & 6).

Wahsakapeequay’s sickness unravels her and drives her away from her community. The moment her community literally turn their backs on her (Fig 7) is when she chooses to invite Windigo to take over her body, becoming one (Fig 8).

Before she is killed, she offers a prophetic warning: “I will make you all pay for this! I will make you suffer for generations!” (69) The windigo, acting symbolically as an agent of colonialism, is never satisfied, and is always searching for new victims.

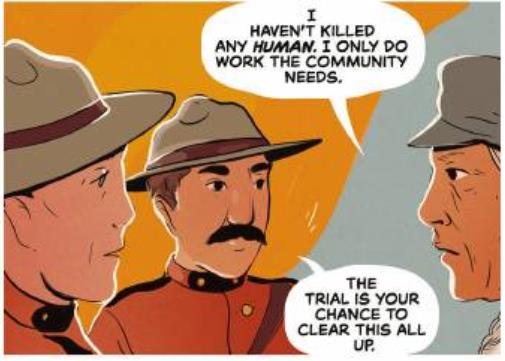

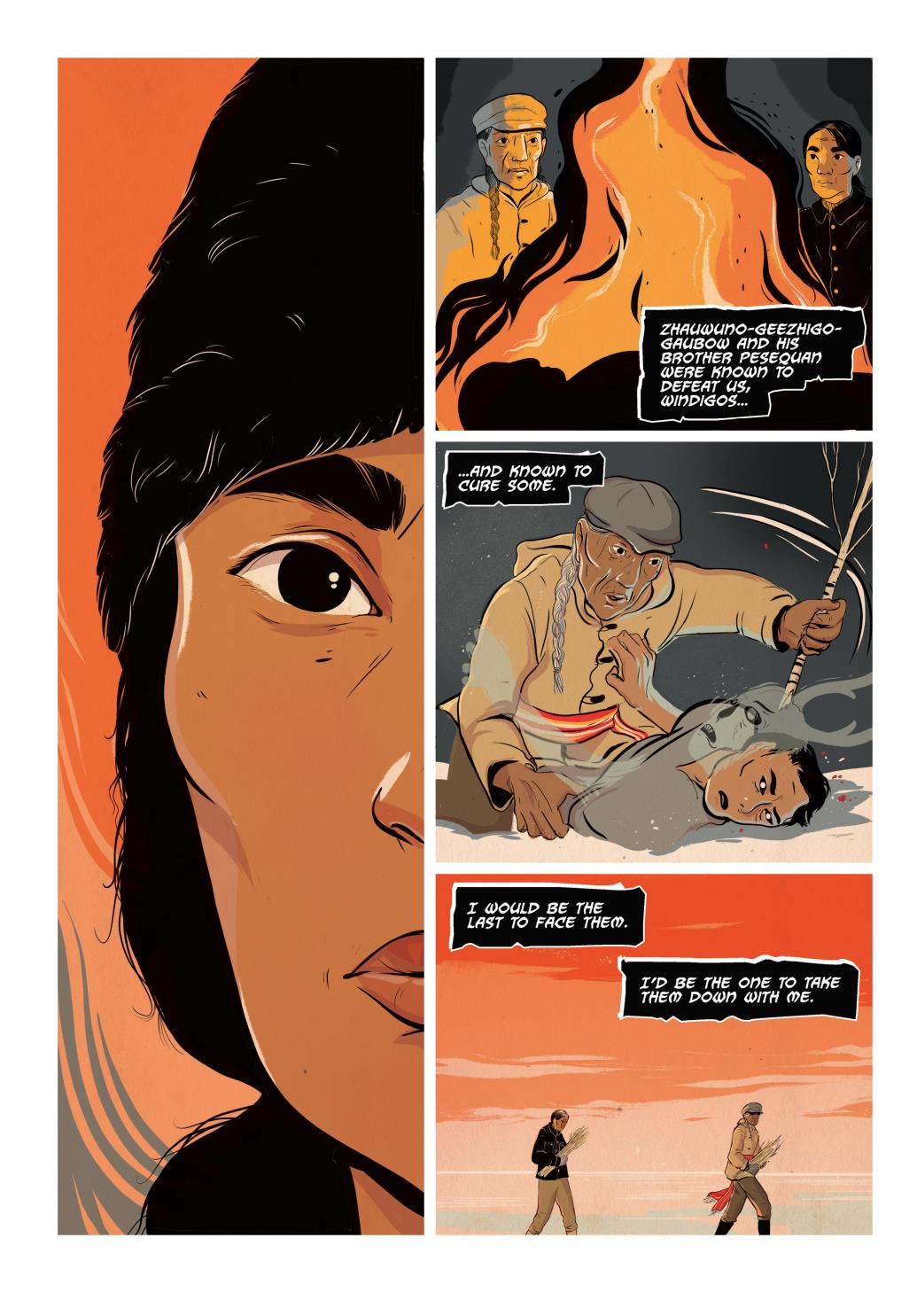

Police as colonial agents: targeting community leaders

The next victims in the story are Zhauwuno-Geezhigo-Gaubow (Jack Fiddler) and Pesequan (Joseph Fiddler), men who selflessly perform the ritualistic windigo slayings for the benefit of the entire community. Jack denies the accusation of murder (Fig 9). It is his responsibility to protect the community from excessive consumption, greed, and selfishness.

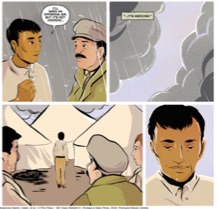

The RCMP officers are set against an orange background, which occurs many more times throughout the story. As Storm writes in the preface, “There are stories that tell of red clouds appearing over an approaching windigo, as a warning or omen” (54). Clearly, Canadian law enforcement is the personification of the windigo’s power.

This colour pattern foreshadows the reappearance of Windigo as Jack and Joseph are led away from their community (Fig 10).

The loss of community, companionship, and cooperation weakens their inner strength, and makes them susceptible to the powers of the windigo (see Killing the Shamen).

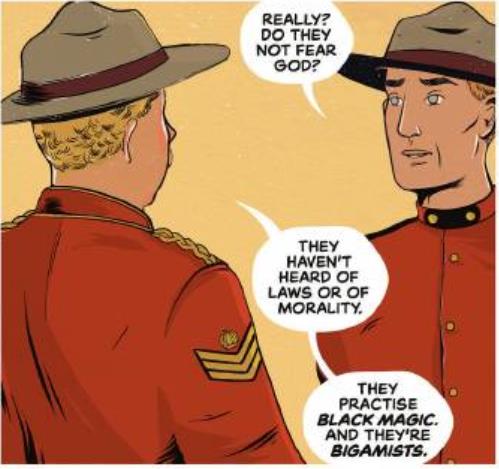

Colonial law: imposing a legal system on a sovereign nation

The arrival of the RCMP officers also signals the arrival of colonial law in Sandy Lake First Nation. When news of the windigo deaths reaches Norway House, it baffles law enforcement (Fig 11).

The officers penetrate the community, and immediately attempt to assimilate and dominate the locals. The officers demand that the community’s “lawlessness” must come to an end (Fig 12 & 13), and assertively declare the RCMP’s authority: “You can enforce this law, or we can” (74).

Canadian law is also enforced in the courthouse, an institution which is inherently discriminatory towards the Indigenous community (Fig 14). The colonial legal system refuses to allow for differences in belief systems or traditional practices and customs. As such, Joseph is sentenced to death for the windigo murders.

The law’s purpose is to displace and destroy individuals in a system of domination, exclusion and assimilation.

Colonial cause and consequence: looking forward and looking back

Without its leaders, the Sucker clan is forced to accept colonial government rule (see The Sucker Clan and Robert Fiddler), which arrives in the form of a priest, a new colonial agent, a new symbolic incarnation of the windigo.

In the final sequence, the red-clouded background dominates and Windigo reappears to echo Wahsakapeequay’s initial warning. Windigo’s gaze directs forward, to the future, and over its shoulder, to the past (Fig 15 & 16). Colonialism has had, and continues to have, devastating effects on Indigenous communities.

In “Red Clouds,” the windigo takes on the symbolic figure of a powerful colonial agent, motivated by greed, selfishness and moral deprivation, whose defeat can only be secured through the strength of community and resilience.

Works Cited

Storm, Jen. “Red Clouds.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, HighWater Press, 2019. 54-80.

back to top

The Haunting of “Red Clouds”

Wencke Rudi, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Rudi, Wencke. “The Haunting of ‘Red Clouds’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 6 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html.

“Red Clouds” is written by Jen Storm and illustrated and colored by Natasha Donovan. This historical comic appears in the anthology 150 Years Retold, a book that features ten comics that each individually present fifteen years of Indigenous history. “Red Clouds” tells the story of Wahsakapeequay, a woman whose body is overtaken by a windigo spirit after it injures her husband. The husband dies from his injuries, leaving Wahsakpeequay and their son to rejoin their community, where she is eventually killed by Jack Fiddler, the leader of the community and the first Indigenous man to be charged as a serial killer in 1907. Her deliriousness caused by the windigo spirit goes beyond the written narrative, as the haunting is present in the comics’ illustrations and coloring, the focus on the characters’ eyes, and the page layout. The visual elements, along with the narrative, make “Red Clouds” a harrowing, haunting comic to read.

The coloring of the comic lends a supernatural sense to the physical pages of the comic. The comic is colored in geotic tones, with reds and light oranges featuring prominently, along with stark blacks, grey-blues and varying shades of white. The earthy tones place the story outdoors,where the windigo spirit first emerges from the trees to Wahsakapeequay in the first panel on page 63.

The transparent silvery appearance of the windigo can be missed easily, as it blends into the surrounding birch trees. The silver colors of the windigo and the white birch trees create an eerie feeling. The earthy tones and continued outdoor setting create the sense throughout the comic that the windigo spirit is constantly in attendance, and it is a matter of it being noticed within its surroundings for it to emerge and conduct another abduction.

The faces of the characters communicate a haunting, especially in the expressions of the eyes. The intricate shadowing and detailing on the faces give depth and dimensionality. The most prominent display of expressive eyes appears on page 60, in the close up on Wahsakapeequay on the left side of her face. The physical closeness of her face creates an intimacy between myself and her, and I feel as though I am looking into her memory through the detailed expression of her eyes.

Her depth of expression in a single eye is completely gone by the last panel three pages later, in which Wahsakapeequay’s eyes are completely white, erased of irises and her face is highly shadowed and detailed. The frequent imagery of Wahsakapeequay throughout the comic give a familiarity to her eyes, her face, and her body; it is clear when it is Wahsakapeequay the woman and Wahoakapeewuay the windigo.

The haunting of “Red Clouds” extends to the setting that works together with the page layout of the comic. The comic’s layout is like tiles, and this presentation, along with the presence of Wahsakapeequay, gives the sense that the images are from her memory. The same effect is felt on the pages that have panels appearing on top of a white background, such as on page 62 that illustrates Wahsakapeequay’s ninabeem getting injured, attempting to make it back, and dying before he can treat his injuries. The illustrated moments feel like memories adrift on the white clouds of winter, memories that are available for this narrative. This begs the question:through whose eyes are we watching this? The narrator of the story is Wahsakapeequay, but the perspective from which the narrative unfolds cannot be from her, for she was not physically present. The unaddressed perspective to these events (for which Wahsakapeequay is not present) implies that the eyes we are looking through are the windigo’s. The eeriness of this perspective is achieved by the consistent coloring that is associated with the windigo, the sequencing of the panels, and the spacing from panel to panel.

Haunting is the motif for the comic, and the earthy tones demonstrates how deeply this goes, from the ground that the birch trees are rooted on, to the bones of the characters. “Red Clouds” is an eerie comic to read, and the comic grips tighter with the characters’ eyes simultaneously watching me and sharing their memories. There is a back and forth of intimacy and coldness between the imagery of Wahsakapeequay and the windigo that leaves me both sympathetic and chilled.

Works Cited

Storm, Jen. Donovan, Natasha. “Red Clouds.” 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. Pp 54-80.

back to top

Narrative and Illustrative Techniques as Methods of Decolonization in Jen Storm’s "Red Clouds"

Julia Wake, MA in Cultural Studies

November 14, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Wake, Julia. “Narrative and Illustrative Techniques as Methods of Decolonization in Jen Storm’s ‘Red Clouds.’”One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

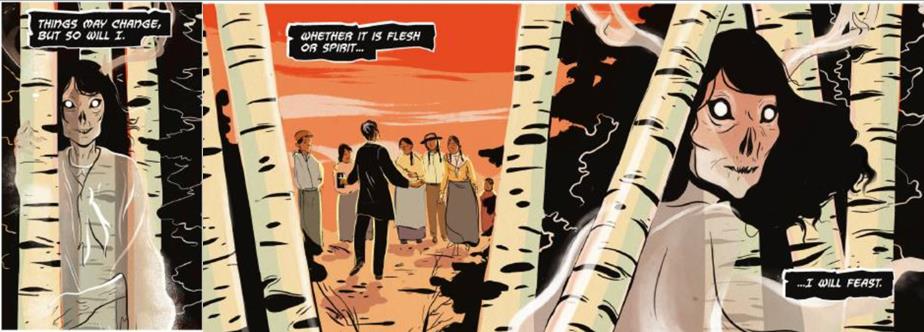

“Red Clouds”, written by Jen Storm and illustrated by Natasha Donovan, uses narrative and illustrative conventions to unsettle and resituate Canadian narratives from an Indigenous perspective. The comic revisits the narrative of the Windigo, a cannibalistic Indigenous figure that has been repeatedly appropriated by Western comics and cinema. Playing with the tension between horror and historical biography, “Red Clouds” tells the story of Zhauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow and Pesequan (Jack and Joseph Fiddler) and their use of shamanistic powers to defeat the cannibalistic spirit that’s known to overtake the physical body (Dictionary of Canadian Biography).

Storm approaches the comic from an Indigenous feminist position (Storm 54), conflating the narratives of multiple women into the singular story of Wahsakapeequay, who holds space for fourteen women murdered by the brothers in attempts to quiet the Windigo.

Illustratively “Red Clouds” mobilizes the intersection of form and content to support a decolonized re-envisioning of cinematic tropes, toeing the line between mainstream illustrative techniques and subversive uses of this form to support counter-narratives. Donovan’s style references her artistic practice as a children’s book illustrator. She uses strong lines, solid colours, and nuanced, neutralized palettes reminiscent of both contemporary children’s picture books and film animation. Her use of colour functions actively within the text; reddish tones foreshadow the arrival of the Windigo (Storm 54), and shifts in palette signify geographical changes in scene. Though “Red Clouds” is polychromatic, Donovan works with a minimalist palette, so these changes in tone are effectively read as intentional.

Other elements of the text also reference the cinematic. The white on black lettering throughout the text is suggestive of subtitles and closed captioning. The inclusion of several full-page and two-page spreads throughout the text function to provide the viewer with additional context. Figures 1 and 2, the opening pages of the comic, feature close-up portrayals of Zhauwuno-geezhigo-gaubow and Wahsakapeequay depicted alongside the title in much the same way that movie opening credits feature the main actors.

Fig. 2. Donovan, Natasha (illustrator). Red Clouds. 2019. This Place: 150 Years Retold. Jen Storm et al. Highwater Press, 2019. pp 57.

Figures 3 and 4, located on the next two consecutive pages, again feature a two-page spread, but this time Wahsakapeequay is the single large-scale figure depicted, sharing space with an overlapping irregular grid of panels. The larger illustration informs the other content on this page, suggesting the narrative is to be read fromWahsakapeequay’s perspective.

Fig. 4. Donovan, Natasha (illustrator). Red Clouds. 2019. This Place: 150 Years Retold. Jen Storm et al. Highwater Press, 2019. pp 59.

In Figure 5, the panels depicting the Windigo’s conquest of Wahsakapeequay function in much the same way. The full-page montage panel consists of three discrete scenes, depicting Wahsakapeequay’s psychological struggle with the Windigo. Read from the top down, Wahsakapeequay’s expression becomes increasingly sinister and evil, and the partial rendition of her form allows for the Windigo to situate itself physically within her space. The final image, situated at the bottom of the page, does not include Wahsakapeequay at all, indicating the Windigo’s full conquest. This montage is overlaid by panels that represent an on-lookers point of view, witnessing Wahsakapeequay’s transformation. Similar to the full-page images located at the beginning of the text, this visual disruption in size provides the viewer with additional information on narrator. Wahsakapeequay’s transformation is the primary event, which the onlookers legitimize by witnessing.

Fig. 5. Donovan, Natasha (illustrator). Red Clouds. 2019. This Place: 150 Years Retold. Jen Storm et al. Highwater Press, 2019. pp 66.

While there are multiple deviations from typical grid pattern, as discussed above, Storm and Donovan consistently favour wide-angle views throughout the text, using extended, horizontal panels that function visually in a manner reminiscent of cinema and television.

Finally, Storm’s use of the Windigo itself within the story speaks back to the cinema. While Indigenous, it’s continued cooption into popular culture results in a cyclical reference through which the subversiveness of the text becomes apparent. Both “Red Clouds” and This Place: 150 Years Retold in its entirety can be interpreted as an effective means of unsettling and repositioning historical Canadian narratives.

The counter-narratives presented in “Red Clouds” work to re-appropriate Indigenous narratives that have previously been coopted by western cultural institutions. As a text, “Red Clouds” uses effective storytelling methodologies, while subtly adjusting the boundaries of historical narrative, graphic novel, and horror, to position itself in critique with pre-existing narratives. The use of comic as medium is significant, as it resituates the Windigo figure within a context that has previously been used as a tool of colonization, effectively disrupting both the medium and the historical narrative.

Works Cited

Storm, Jen, Natasha Donovan (Illustrator). “Red Clouds.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. pp 54-80.

“Zhauwuno-Geezhigo-Gaubow.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, University of Toronto. www.biographi.ca/en/bio/zhauwuno_geezhigo_gaubow_13E.html. Accessed 10 October 2019.

back to top

Birch Trees and Double Standards in “Peggy”

Andrew Brown, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Brown, Andrew. “Birch Trees and Double Standards in ‘Peggy’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html.

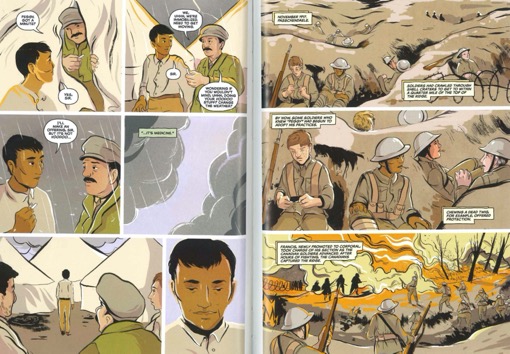

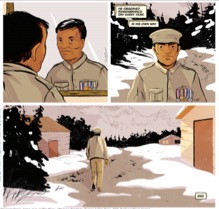

David A. Robertson and Natasha Donovan’s graphic short story “Peggy,” in the anthology This Place: 150 Years Retold, is about Francis Pegahmagabow, a decorated World War I soldier and Anishinaabe chief. In “Peggy”, the Canadian military respects Francis as a soldier, but the Canadian government denies him access to better services as an Anishinaabe. This suggests a double standard in the way Francis is treated.

At the same time, birch trees appear throughout “Peggy,” and they are culturally significant to the Anishinabeg:

- They often use the outer bark to start fires

- Older trees produce nutritious sap

- The Anishinaabeg use birch wood to build structures since they believe birch wood is never struck by lightning (Geniusz 60-61)

Robertson and Donovan use the cultural significance of birch trees to show there is no double standard in how Peggy is treated. In fact, the birch trees illustrate that neither the military, nor civilian Canadian society treats him fairly.

The Anishinaabeg and Tree Cutting

During Francis’ lifetime (1891-1952), Canada’s Indian Department required the Anishinaabeg to have permits to cut down trees. If an Anishinaabe had enough income, this permit would be denied, forcing them to buy wood from outside the community. This limited the wealth in Indigenous communities. As a result, it was illegal for some Anishinaabeg to cut birch trees on their own property for stove wood (Brownlie 68). Robertson and Donovan represent this historical context in the following panels using cut birch trees.

In “Peggy,” these two panels appear in the World War I narrative. The birch trees seem out of place in the narrative, but the panels parallel each other. The trees’ positions match the soldiers’ positions. So, if the trees represent people, and birch trees are significant to the Anishinaabeg, then the trees echo the Anishinaabeg.

However, there are three wounded soldiers in the first panel, which also parallels the three cut trees. This symbolizes that their Anishinaabe identity, represented by the trees, is hurt from being “cut off.” Therefore, the two panels parallel the damage to their territorial lands and resources to the injuries and deaths of the First World War.

Francis as a Canadian Soldier

Comics are read left to right, and down the page, but reading the same panels out of order creates new meanings (Cohn). Reading the same wartime/birch tree panels in reverse order reveals how Francis is exploited as a soldier. The birch tree panel shows the Anishinaabeg as oppressed, which then continues onto the soldiers in the wartime panel.

Canada conscripted over 600,000 men to fight in World War I; it was optional for Indigenous men (“The Cost of Canada’s War”). In “Peggy,” the above anonymous solider asks Francis why he enlisted (Robertson 93). The question itself implies the soldier was not interested in fighting in World War I. This soldier represents the many others who did not voluntarily consent to fight, kill, or die for their country; rather, they are pawns in an international conflict.

Francis volunteered to fight in World War I, but it was not in his best interest:

- At the Battle of Ypress, the enemy released “6,000 cylinders of chlorine” gas onto his battalion (88).

- He fights at Passchendaele, which was a “senseless slaughter” (Robertson 88,96; Roy and Foot).

- Francis killed “378 enemy soldiers,” which he regrets by stating he killed “too many” (Robertson 91).

- It is a miracle he survives the war, but he consequently develops mental health issues (99).

So, the Canadian military disregards Francis’ own health and values so they may achieve their own goals.

“Peggy” still portrays Francis as a hero. However, the cultural importance of birch trees shows that there was never any double standard – the Canadian government mistreats Francis as both an Anishinaabe and a soldier. When reading This Place, pay attention to the plants in other chapters. They also tell stories since they share this place with us, thus providing “new skills to help us survive and flourish as peoples” (Justice 76-77).

Works Cited

Brownlie, Robin. “Man on the Spot: John Daly, Indian Agent in Parry Sound, 1922-1939. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association. vol. 5, no. 1, 1994. pp. 63-86.

Cohn, Neil. “Navigating Comics: An Empirical and Theoretical Approach to Strategies of Reading Comic Page Layouts.” Front Psychology. vol. 4, no. 186, 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm. gov/pmc/articles/PMC3629985/. Accessed 21 Oct. 2019.

“The Cost of Canada’s War.” Canadian War Museum. https://www.warmuseum.ca/war history/after-the-war/legacy/the-cost-of-canadas-war/. Accessed 27 Oct. 2019

Geniusz, Mary Siisip. Plants Have So Much To Give Us, All We Have To Do Is Ask: Annishinaabe Botanical Teachings. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

Justice, Daniel Heath. Why Indigenous Literatures Matter. Waterloo: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2018.

Robertson, David A., writer. “Peggy.” Illus./Coloured by Natasha Donovan. This Place: 150 Years Retold. High Water Press, 2019. pp. 82-108.

Roy, R.H., and Richard Foot. “Canada and the Battle of Passchendaele.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/battle-of-passchendaele. Accessed 35 Oct. 2019.

“Ypres 1915” Veterans Affairs Canada. https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/first-world-war/canada/canada4. Accessed 27 Oct 2019.

Further Reading:

Koennecke, Franz. “Francis Pegahmagabow.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://.www.thecanadianencyolopedia.ca/en/article/francis-pegahmagabow. Accessed 25 Oct 2019

back to top

Faded History: Representations of Indigenous War Veterans in "Peggy"

Blake Carter, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Carter, Blake. “Faded History: Representations of Indigenous War Veterans in “Peggy”. One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.htmlwww.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/eventsblog

Introduction/Summary Of “Peggy”

- “Peggy” is a historical-biographical comic written by David A. Robertson and illustrated and coloured by Natasha Donovan.

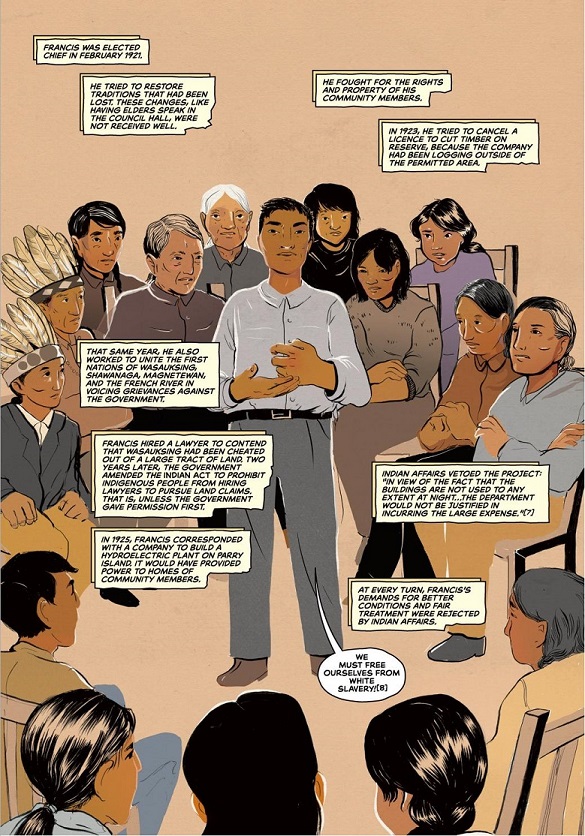

- The comic tells the story of Francis "Peggy" Pegahmagabow, who served as a soldier in World War I (despite not being conscripted) and became one of the most effective snipers in history. While Peggy’s war-time contributions are fairly well-known, Robertson and Donovan also describe Peggy’s experiences off the battlefield and journey to become the Supreme Chief of the National Indian Government.

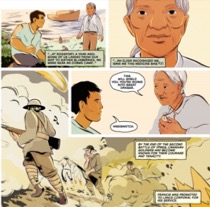

- Through the style (art style and colour) and content (both during and after the war) of their comic, Robertson and Donovan create a story that highlights Peggy’s distinctively traumatic experiences as an Indigenous soldier, and how his experience was not valued by the dominant colonial power in Canada and Britain during his lifetime.

Style (Colour)

Desaturated/Pale Colours

- Throughout “Peggy,” Donovan draws attention to what is and is not valued by the dominant colonial power through the careful use of colour.

- The majority of the colours in “Peggy” are desaturated and pale (mostly shades of brown, green, orange, and grey) (see fig. 1).

- The desaturated colours create a washed-out feeling, signifying that Peggy’s experience as an Indigenous soldier is unimportant to dominant culture and fading out of relevance from a colonial perspective.

Fig. 1 Peggy in the war, highlighting desaturated colour palette: Page 94 and 95 of David A. Robertson and Natasha Donovan’s “Peggy.”

Intrusion of vibrant colours

- While Donovan uses mostly desaturated and pale colours, there are two important points in the comic where vibrant colours are used. The British flag and various medals that Peggy receives for his service are both drawn in bright blues and reds that stand in sharp contrast with the dull colours found everywhere else on these two pages (see fig. 2). By using colour specifically in this way, the comic once again suggests that attention is payed more to patriotic values, ideas, and celebrations following the Allies victory instead of to the people actually involved in the conflict, especially when the subject is an Indigenous soldier.

Fig. 2 Depiction of British flag and military medals in bright colours contrasting the other desaturated colours: Page 100 and 101 of David A. Robertson and Natasha Donovan’s “Peggy.”

Content

During the war

- Robertson uses the story’s dialogue to draw attention to the horrors Peggy was subjected to during the war, and how his difficulties did not come to an end when he came home.

- In a conversation with a fellow soldier, Peggy reveals that he is troubled by his role as a sniper. He tells his companion that he has not missed much on account of shooting all his life, though he admits “Not like this . . .” (90), and that the number of people he has killed is simply “Too many” (91).

- Soon after, Peggy’s companion steps on a mine and is killed in the resulting explosion. Peggy attempts to rouse the man, feebly shaking him and saying “Hey…Hey…” before realizing that there is nothing he can do (91).

After the war

- Robertson also draws the reader’s attention to the many difficulties faced by Peggy after the war.

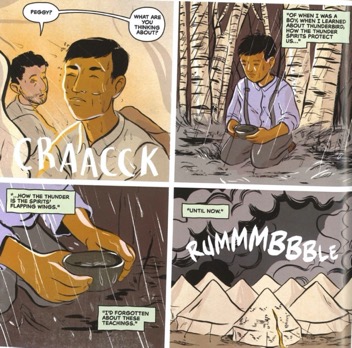

- One such example occurs when Peggy, peacefully asleep back home with his wife in Wasauksing, is woken up by the sound of thunder. Peggy tells his wife “…It’s just. Before, when I heard thunder, I felt safe. Now, it’s different. Now, it reminds me of war” (99).

- This scene is particularly relevant as it addresses the unique Indigenous experience Peggy has of the war. Peggy’s comments on how he no longer feels safe when he hears thunder is especially sad when the reader recalls how he describes thunder earlier in the story: “. . . when I was a boy . . . I learned about the Thunderbird, how the thunder spirits protect us… how the thunder is the spirits’ flapping wings” (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Peggy recalls learning about Thunderbirds: Page 92 of David A. Robertson and Natasha Donovan’s “Peggy.”

- Because of the traumatic events he experienced during the war, Peggy no longer recalls his people’s teachings about the Thunderbird and is unable to associate thunder with anything but the violence and madness of the war.

Conclusion

- Robertson and Donovan use the style and content of their comic to present Peggy’s experience as an Indigenous soldier living in a world that still privileges dominant colonial perspectives.

Works Cited

Robertson, David A. “Peggy.” Illustrated by Natasha Donovan. This Place: 150 Years Retold. Highwater Press, 2019, pp. 84-108.

back to top

“We Will Keep Fighting:” A First Nation War Story in “Peggy”

Sophia Hershfield, BA in English

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Hershfield, Sophia. “’We Will Keep Fighting:’ A First Nation War Story in “Peggy.” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

The chapter “Peggy” in This Place: 150 Years Retold is written by David A. Robertson and illustrated and coloured by Natasha Donovan. This chapter tells the story of Francis Pegahmagabow, also known by the nickname Peggy, an Anishinaabe(Ojibwa) soldier from the Parry Island reserve who fought in the First World War.

While the first two splash pages may suggest a standard contrast between the pastoral nature of home and the horrors of war, this chapter complicates that dichotomy, and disrupts the typical Canadian war narrative. Robertson and Donovan use stylistic elements, especially sound, to represent perilous and onerous conditions, both at war and at home, and thematic elements, especially nature, to subvert Francis’s connection to war and his country. While the conditions of fighting Germans in the trenches are undeniably brutal, Francis is forced to fight the Canadian government under different, but still difficult, circumstances. In “Peggy,” Robertson and Donovan show that, for Indigenous soldiers in the First World War, the fight did not end on Armistice Day.

The use of onomatopoeia and vivid visual images in this chapter creates a visceral representation of trench warfare. Throughout the first half of the chapter, Robertson and Donovan show numerous loud, chaotic, and crowded moments both on and off the battlefield, such as the sudden and violent death of Francis’s scouting partner from a landmine.

This moment is especially striking compared to the quiet panels on the page before.

Donovan and Robertson show the continued trauma of the war in Francis’s life during a thunderstorm when Francis is back home. He is woken up by the sound of thunder and he admits that the sound “reminds [him] of war” (fig 3).

Donovan and Robertson use sound to portray the obviously horrible effects of war and how it impacts Francis in different ways.

In contrast, after he returns from war, there are more silent panels. One example is a striking splash page which shows Francis speaking to a group of people, but there is only one small speech balloon in which Francis is actually speaking.

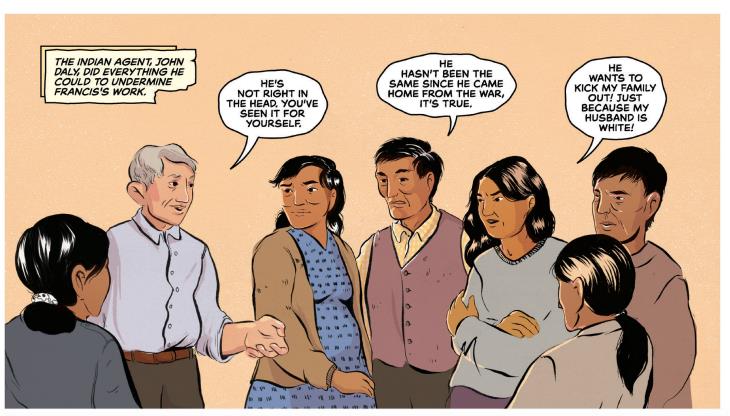

On the next page, Donovan and Robertson show the whisper campaign started by Indian agent John Daly that served to sabotage Francis. Francis speaks very little, but Daly and those who wish to undermine Francis speak a lot.

Rather than being a sign of calmness, Francis’s increasing silence as the chapter goes on parallels the way that Francis is silenced by Indian Affairs in his fight for rights and property for his community.

Donovan and Robertson emphasize the importance of nature and Francis’s relationship with nature throughout the chapter. In Francis’s childhood, nature is a source of comfort and protection, and war violates both nature itself and his relationship to nature. For example, Francis explains his relationship to the Thunder Spirit as a source of protection.

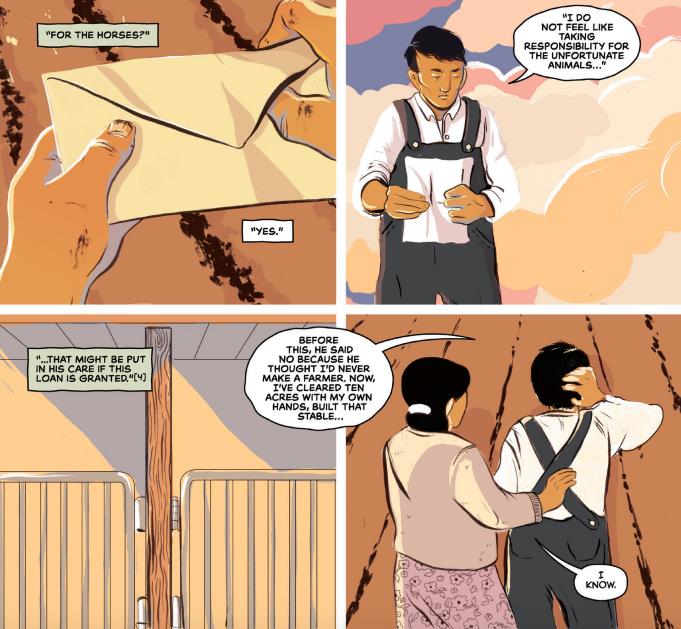

There are many images throughout the chapter that show earth mutilated by landmines as well as barren trees destroyed by fire and gas. While this type of imagery is not uncommon in war narratives, for Francis, the government’s violation of nature does not stop in the trenches. Even when Francis has returned from war, the Canadian government still tries to interfere with his connection to nature. A notable example of this is when Francis is denied a loan request for horses for his farm by the Indian agent.

After returning from war, Francis is forced to continue to fight, but instead of fighting Germans, he is fighting a government that has colonized his people and his land.

Francis’s story is an unusual history of war. In the first half of the chapter, he is fighting for Canada, and in the second half he is fighting against Canada. Although the chapter initially seems like a simple dichotomy between the horrors of war and the peace back home in Canada, “Peggy” is much more complex.

Robertson and Donovan subvert the traditional war narrative with the unexpected use of familiar elements. Francis is oppressed by noise and also by silence. He is comforted by nature, but his connection to nature is exploited. Francis’s hardships, both in the trenches and at home, are mediated by the colonial forces of the Canadian government.

Works Cited

Robertson, David and Natasha Donovan. “Peggy.” This Place: 150 Years Retold. HighWater, pp. 83-108.

back to top

"Peggy": Engaging with Indigenous Identity and Culture through Colour

Sabrina Zacharias, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Zacharias, Sabrina. “’Peggy’: Engaging with Indigenous Identity and Culture through Colour.” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

Fig. 1 “Corporal Francis Pegahmagabow” Canada and the First World War. George Metcalf Archival Collection. Canadian War Museum, Ottawa.

Who Was Francis “Peggy” Pegahmagabow?

As David Robertson states in his introduction to “Peggy”, Francis Pegahmagabow was “one of the most effective snipers in history” (Robertson 82). Pegahmagabow has been credited with 378 kills and 300 captures. For his service, Francis Pegahmagabow became the most decorated Indigenous soldier during the First World War.

After the War

Francis’s story does not end there, however. When he returned home from the war, he became Chief of the Wasuaksing First Nations, Councillor and finally the Supreme Chief of the Native Independent Government (Archives Canada 100 Stories).

“Peggy”: This Place: 150 Years Retold

“Peggy” is the comics biography of the Ojibwa Chief, soldier, and Indigenous rights advocate Francis “Peggy” Pegahmagabow of the Wasauksing First Nation, written by David Robertson and illustrated by Natasha Donovan. “Peggy” highlights the importance of culture and identity, and how these two constructs are inextricable from one another. Through use of the colour purple as a symbol for Francis Pegahmagabow’s cultural identity, “Peggy” explores the struggle of culture and identity for Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The Colour of “Peggy”

Fig. 2 Francis’s flashback: Pages 87 and 92 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

Fig. 2 Francis’s flashback: Pages 87 and 92 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

- From the beginning of the chapter of “Peggy”, Donovan uses the colour purple as a constant symbol of Francis’s culture and identity.

- The connection is created through the panels on pages 87 and 92, in flashback sequences to when Francis is a child. Francis is wearing a purple shirt, and this associates the colour with Francis.

During the War

- While fighting for Canada, Francis remains fundamentally Ojibwa, continuing his beliefs and practices. Despite a new-found equality in the army, “Here we’re like equals. I even outrank soldiers. Back home it’s not like that” (Robertson 93), Francis remains steadfast in his identity, and this is represented through the purple symbolism reappearing at key moments (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Key Moments for Francis’s Identity: Pages 89 and 94 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

After the War

- Returning from war leaves Francis with an internal struggle with the person he was before the war, and person he has become. He is no longer comforted by the thunder as he once was, as it now reminds him “of war” (Robertson 102), rather than the Thunderbird (fig. 4).

Fig. 4 Francis Fears the Thunder: Page 99 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

- The Indian Agent and the Canadian Government are hindering Francis and other Indigenous peoples and Indigenous soldiers from accessing the benefits that are rightfully theirs. Thus, Francis faces the inability to access the Soldier Settlement Act (fig. 5). Despite all that he gave during the war, Francis must fight for what settler soldiers would receive automatically cause of his Ojibwa culture and identity.

Fig. 5 No Access to the Soldier’s Settlement Act: Page 102 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

- From page 105 onwards, Francis tells his son how a channel on Wasuaksing land was formed, explaining that in Ojibwa tradition there are stories for everything, and that each of these stories come down to the idea of life.

- At this point Donovan begins to work purple into the scenery very frequently, signifying the connectivity of the natural world to Francis’s Ojibwa culture and identity (fig. 6). Donovan’s use of the colour imagery emphasizesrancis’s words to his son, supporting the idea that Francis, an Ojibwa man, is connected to the land in ways settlers can never be: “It doesn’t matter what they say, son. Indian Affairs, Canada, or King George. This is our land” (Robertson 105).

Fig. 6 Francis’s identity and nature: Pages 105 and 107 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

Remembrance Day

It is also important to note the spaces that Francis inhabits that are void of symbols of his identity and culture, such as the Remembrance Day sequence.

Fig. 7 Francis Reclaims his Uniform: Page 108 of Robertson and Donovan’s “Peggy.”

- The lack of purple in these panels speaks to the duality of Francis’s identity. By reclaiming his uniform, Francis is once again acknowledging the efforts he put into the war, for the country (fig. 7). He can be considered a Canadian soldier, but that role is not defining of his Indigeneity.

Works Cited

Archives Canada. “Francis Pegahmagabow.” Library and Archives Canada, The Government of Canada, 7 Aug. 2018, www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/100-stories/Pages/pegahmagabow.aspx.

Archives Canada. “Item: F Pegahmagabow.” Library and Archives Canada, The Government of Canada, 16 Oct. 2015, www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/military-medals-1812-1969/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=89018&.

Robertson, David A. and Natasha Donovan. “Peggy.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. Print. 82-108.

“Corporal Francis Pegahmagabow.” Canadian War Museum, Ottawa, www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/objects-and-photos/photographs/photographs-of-prominent-people/corporal-francis-pegahmagabow/?back=1596&anchor=2431.

back to top

"Let’s Stick with Rosie": Names and Inuit Secrets in "Rosie"

Rhys Delios, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Delios, Rhys. “‘Let’s Stick with Rosie’: Names and Inuit Secrets in ‘Rosie.’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

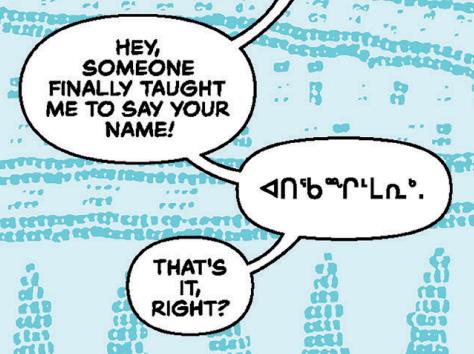

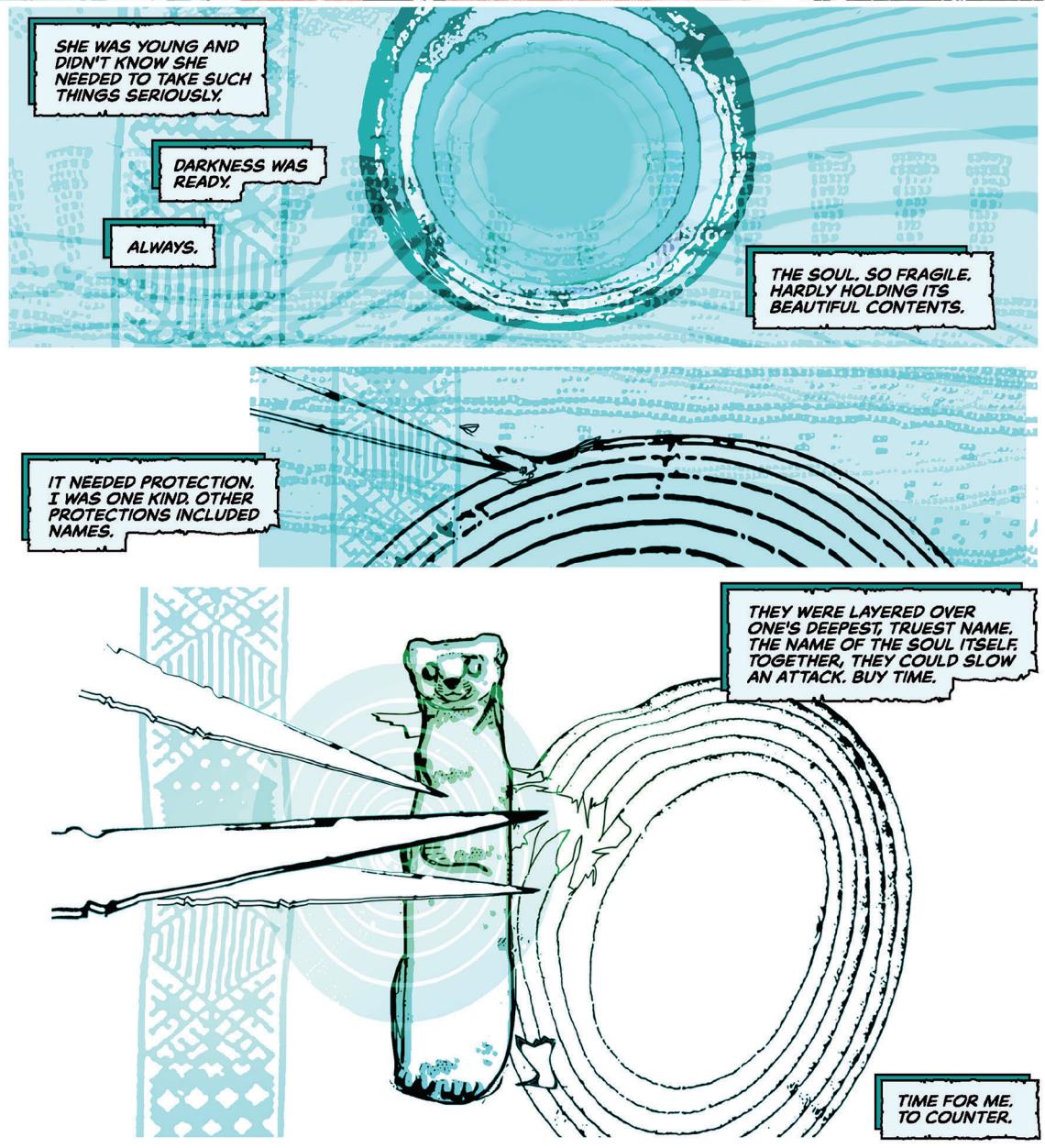

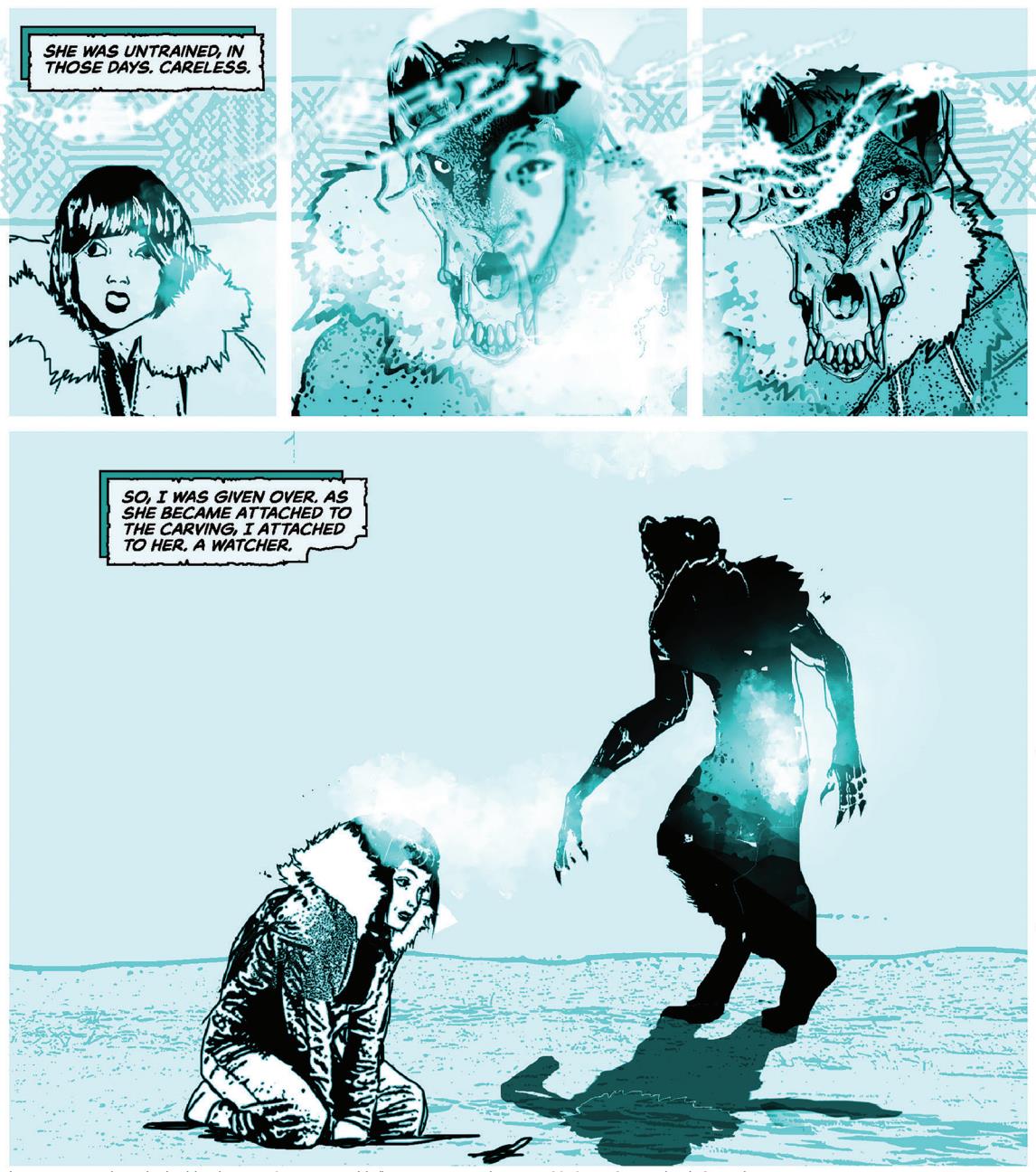

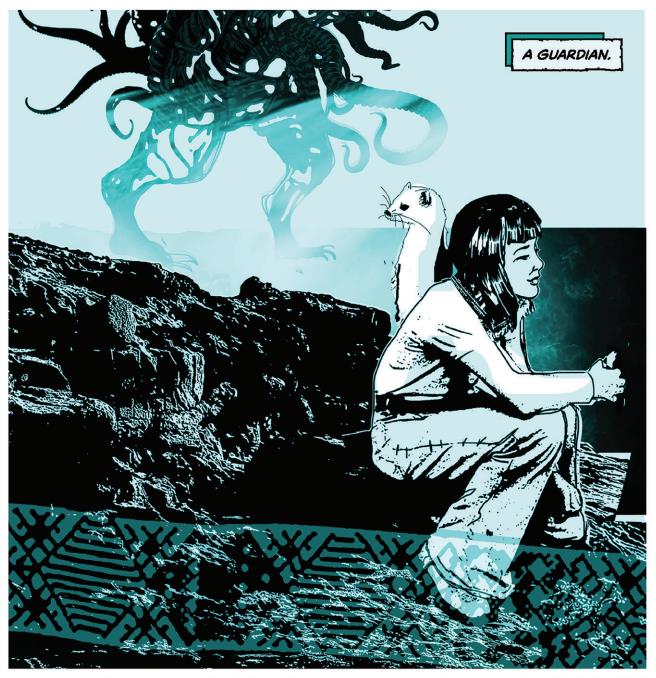

Writers Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley’s and illustrator GMB Chomichuk’s comic "Rosie" draws on Inuit culture and knowledge regarding names and the supernatural to ground the titular character in Inuit culture, mysticism, and secrets, and to inform the visuals of the comic. Pauki’s names, and the connection to the supernatural and spiritual they suggest, act as a vehicle through which the visual layers of the comic peel back and allow the supernatural to make itself known to both Pauki and the reader.

“Rosie” is set in the 1940s and follows Pauki, an Inuit girl who lives in the Arctic, from the perspective of her spiritual guardian, given to her by the shaman Iqqaq. A Canadian trader approaches Pauki and asks her to tell the shaman, Aasivak, that he has brought her dolls. When Pauki does this, Aasivak attacks her, but Iqqaq protects Pauki and the attack turns back onto Aasivak.

The comic opens with the following set of five panels (Fig. 1):

Just as the narrative boxes describe the stripping of the flower blossom, Chomichuk strips the colour from the panels, leaving only a monochromatic, pale blue wash. As the comic continues, occasional auras of green, red, yellow, and purple accompany the pale blue; the purple tones are only used in these first panels or attached to Pauki herself.

Like the colours, there is a similar stripping away in Pauki’s names in her introduction to the narrative. The first shot of Pauki accompanies narrative boxes that explain her names; this introduces the Inuit concepts of atirusiit and aqausiit to the narrative. The narrator explains the origin of Pauki as a nickname that becomes an essential part of Pauki’s identity (fig. 2 and 3).

I use the name Pauki because both her mother and the guardian use the name Pauki, and because it is the only name with a detailed explanation. The narrator also translates Pauki’s other names (fig. 4):

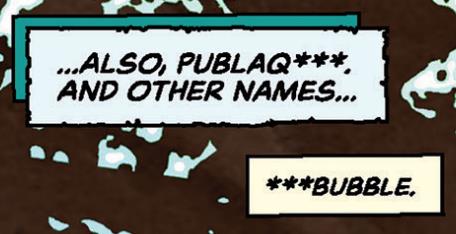

While these names are somewhat tongue-in-cheek. because Pauki does have many names, they do play a larger role in the narrative. By naming her Atiittunnuaq and Atiqanngitturjuaq, the writers foreshadow Pauki revealing her true name to the buyer. These names are also somewhat cheeky, as the writers only reveal her true name in Inuktitut syllabics, leaving her true name incomprehensible to non-Inuktitut speakers (fig. 5).

While it might be possible to find a translation of her true name, Pauki’s response to the buyer is also said directly to a settler reader (fig. 6).

There is power in keeping her name in untranslated Inuktitut syllabics, and the writers’ choice to do so challenges the colonial desire to know and own everything.

Inuit elders describe the soul, tarniq, as a bubble, which connects to one of Pauki’s names (fig. 7). Pauki’s name connects her to the spirit and to the supernatural world.

Both Pauki and her guardian are often surrounded by a series of circles that look like bubbles (Fig. 8 and 9).

So, the narrator’s description of the soul suggests that the circular motif it accompanies are visual representations of the soul.

Pauki’s connection to the spiritual allows both Pauki and the reader to see beyond the layers of reality into the world of the supernatural. In the following panels, Pauki is notably unchanged, while her playmate takes on a wolf-like appearance (fig. 10). This firmly plants the supernatural as being from Pauki’s perspective, but not occurring universally.

After this moment, more supernatural elements enter into the visual space, specifically as spiritual companions to the comic’s characters. The first guardian who makes an appearance is the buyer’s (fig. 11).

This guardian's appearance immediately draws a connection to European folklore about fairies, while the other spirits in the comic are animals indigenous to the land surrounding them.

The contrast between humanoid and animal makes the buyer's companion, and the buyer himself, seem entirely alien to the environment they now occupy. (Which, in fairness, they are.)

Qitsualik-Tinsley, Qitsualik-Tinsley, and Chomichuk ground Pauki in Inuit culture through her many names, interweaving their meanings throughout the narrative, and maintain a level of secrecy regarding Pauki’s true name, combatting the European prerogative of ownership through knowledge. Pauki’s names inform some supernatural elements of the narrative, bringing in the visual elements of the publaq and allowing her to open up the visual sphere to the spirits seen around the characters.

Works Cited

Qitsualik-Tinsley, Rachel, Qitsualik-Tinsley, Sean, Chomichuk, GMB. “Rosie.” This Place: 150 Years Retold, Highwater Press, 2019. pp. 110-136.

back to top

Truth, Justice, and the Indigenous Way: Superhero Narratives and Indigenous Resistance in Katerie Akiwenzie-Damm’s "Nimkii"

Sasha Bouché, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Bouché, Sasha. “Truth, Justice, and the Indigenous Way: Superhero Narratives and Indigenous Resistance in Katerie Akiwenzie-Damm’s ‘Nimkii.’” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html

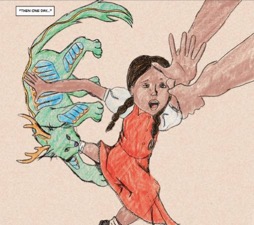

In This Place: 150 Years Retold, “Nimkii” uses various storytelling elements and iconic imagery that characterize superhero comics. The comic centres Nimkii, an Anishinaabe woman who shares the story of her troubling past with her young daughter. Nimkii’s story is one of trauma, loss, and resistance that characterizes her as a dynamic and resilient Indigenous woman. In this way, the comic reinterprets the “superhero origin story” and frames the Indigenous protagonist as a hero in her own right. Nimkii works through her traumatic past by devoting herself to Indigenous resistance efforts and protecting her community. The comic also contains dynamic images and symbols that echo superhero iconography that present “Nimkii” as a uniquely Indigenous take on the traditional superhero comic. “Nimkii” is thus an example of how Indigenous storytelling can use the historically white-dominated medium of comics to promote positive Indigenous representation.

The origin stories of many popular superheroes and how they decide to be heroes align with “Nimkii” in various ways:

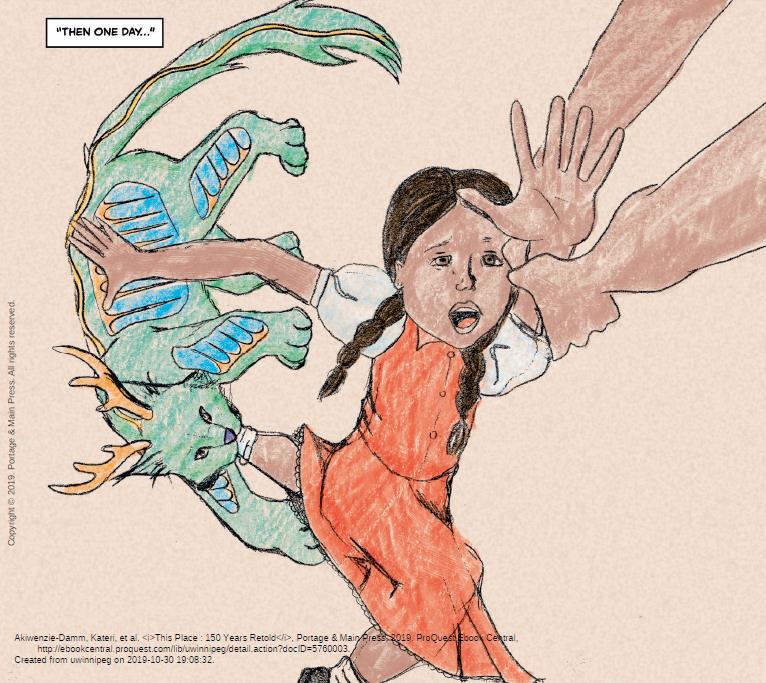

- Nimkii shares how she was taken from her mother and how the experience affects her and shows this traumatic event through pencil crayon drawings, instead of showing graphic violence (See Figure 1).

- What sets superhero comics apart from other tragedies is the hero’s will to survive, to protect their communities, and to combat injustice.

- Superhero comics can romanticize adversity and depict sensationalized violence. Comparing “Nimkii” to superhero comics without acknowledging this would render Indigenous identity synonymous with trauma and injustice.

- For superheroes, the cataclysm in their past is typically a random event, like a freak accident or, say…their home planet exploding. But for Nimkii, her past traumas emerge from the cataclysm of European colonization, not some random disaster.

- Nimkii’s past contextualizes her struggles, but is not the source of her strength.

Figure 1: Nimkii as a child being dragged away by the Great Lynx, Mishi-Bizhiw (Akiwenzie-Damm 146).

“Nimkii” also emphasizes the power of storytelling, both narratively and visually:

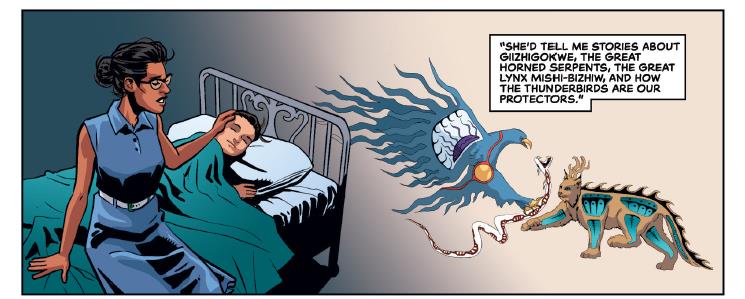

- In one sequence, Nimkii explains how her mother’s stories shaped her cultural understanding (See Figure 2). This reinforces the cultural importance of storytelling for both Nimkii and her daughter.

- Stories are Nimkii’s “superpower” as these stories empower communities, provide historical context, and pass on cultural knowledge.

- This kind of storytelling warns her daughter about colonial violence while integrating cultural beliefs that will protect her in times of struggle.

Figure 2: Nimkii explains the importance of stories (Akiwenzie-Damm 142).

For Nimkii, the Thunderbird figure represents a sense of cultural belonging that is critical to her survival:

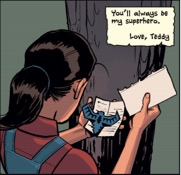

- At the end of the comic, Nimkii dons a t-shirt with an emblem of a Thunderbird, the same emblem her foster brother, Teddy, draws for her (Figure 3). This emblem echoes superhero iconography, which symbolizes a hero’s origin or hope for those who require their protection.

- For mainstream superheroes like Superman, some iterations dictate that his emblem is his family crest, a visual reminder of where he comes from. In the same way, the Thunderbird connects Nimkii to her memories of Teddy, her mother, and her culture.

Figure 3: Nimkii finds Teddy's suicide note along with a paper Thunderbird (Akiwenzie-Damm 162).

“Nimkii” presents a uniquely Indigenous interpretation of the popular superhero. Nimkii’s character is a dynamic Indigenous woman devoted to protecting her family and community. She presents a more attainable vision of heroism that does not rely on graphic violence but instead on a sense of duty and collective belonging. Though Nimkii’s story is rife with colonial violence, her culture and relationships provide her with the strength to escape the clutches of her past traumas. As a superhero comic, “Nimkii” reimagines the common tropes of the genre in a way that promotes a culturally significant code of ethics centred around community, compassion, and colonial resistance.

Works Cited

Akiwenzie-Damm, Kateri, et al. This Place: 150 Years Retold, Portage & Main Press, 2019.

ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/

uwinnipeg/detail.action?docID=5760003. p. 139 – 164.

Harbet, Xandra. “When Did Superman’s ‘S’ Symbol Change Its Meaning?” ScreenRant, 9

October, 2019, https://screenrant.com/superman-s-symbol-meaning-explained/

“The History of Superman!” Youtube, uploaded by Variant Comics, 26 June, 2013,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SvGwLHODZgo

Romagnoli, Alex S., and Gian S. Pagnucci. “5. The Iconography of Superheroes.” Enter the

Superheroes : American Values, Culture, and the Canon of Superhero Literature. E-book, Scarecrow Press, 2013. https://books.google.ca/books?id=rEFYXyA7sP4C&dq=superhero+iconography&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Rosenberg, Robin. “The Psychology Behind Superhero Origin Stories.” Smithsonian.com,

February 2013, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-psychology-behind-superhero-origin-stories-4015776/.

“Thunderbird.” Gibagadinamaagoom, 8 May 2013,

http://ojibwearchive.sas.upenn.edu/thunderbird- cultural-context.

back to top

The Thunderbird as a Symbol of Resistance and Resilience in “Nimkii”

Kell Hagerman, BA in English

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Hagerman, Kell. “The Thunderbird as a Symbol of Resistance and Resilience in “Nimkii. ” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html.

Told by an Anishinaabe mother to her young daughter, “Nimkii” is a story of cultural survival that uses the thunderbird as a symbol of resilience and hope in the midst of struggle. The comic follows a narrative of two Anishinaabe children in oppressive foster care placements related to the Sixties Scoop. Nimkii relates her experiences within the child-welfare system to her daughter, and tells her about community resistance against removing children from their homes in 1990. Spiritual creatures appear in both timelines, and the events are connected through Nimkii’s artwork and her mother’s storytelling.

In Nimkii’s adult home, bright illustrations cover the walls, caught up with childhood experiences of loss, disorientation, and helplessness from which she hasn’t moved on (Fig. 1). These drawings in the background of the initial panels hint at layers beyond the comic’s present that are unpacked through Nimkii’s stories.

The comic’s creators convey that spiritual beings are as relevant to Indigenous heritage and realities as are the consequences of Residential Schools and systems of colonial violence, and that the spaces of each intersect.

When Nimkii’s mother tells her stories of Anishinaabe creatures, the artist pictures them alongside the bedtime scene, drawn out of the mother’s imagination and onto the fabric of the page (Fig. 2). The Anishinaabe stories are Nimkii’s memento of her mother, and a guide for her and the Indigenous kin with whom she shares them.

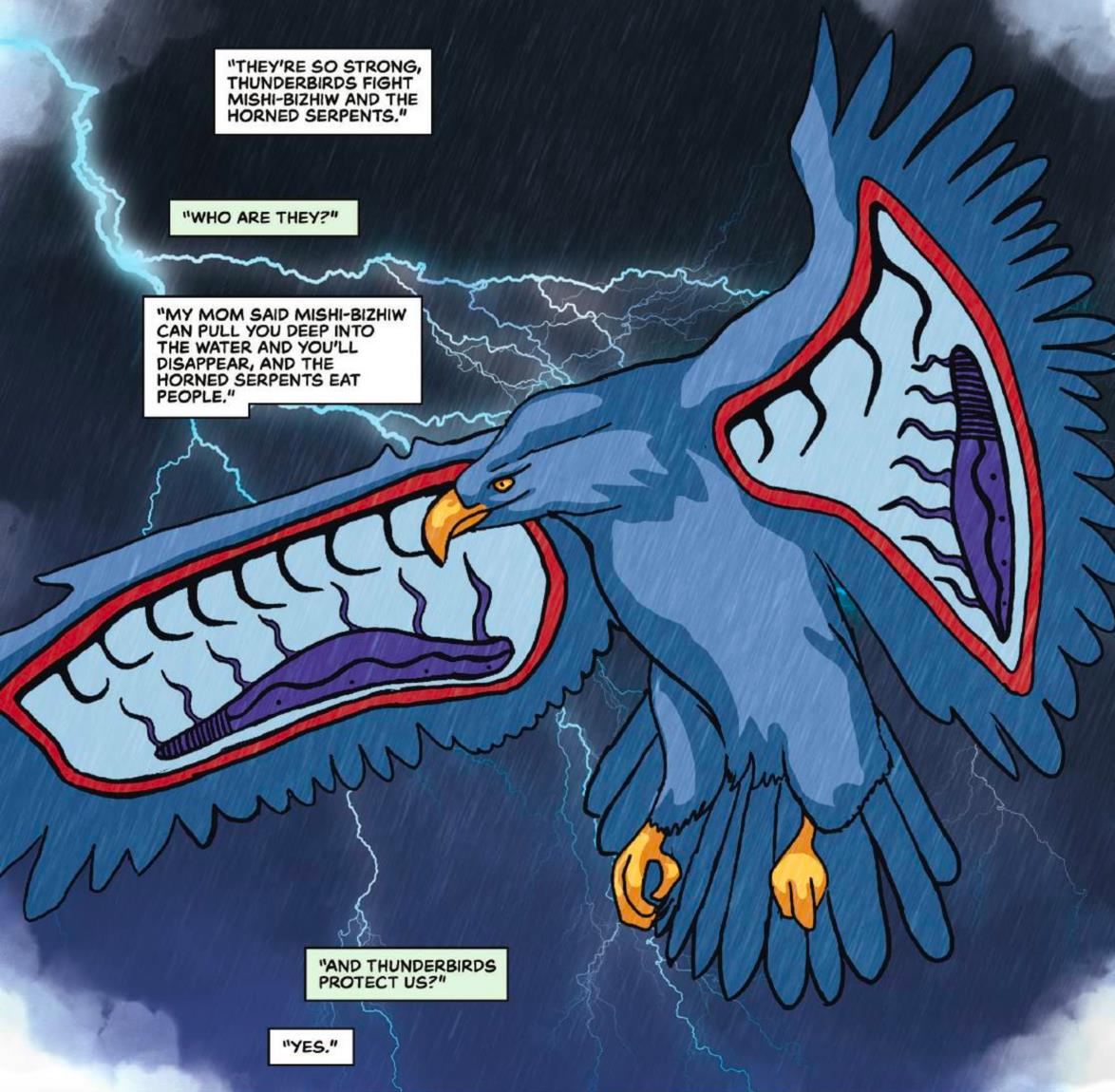

The spiritual beings provide new bases of understanding for Nimkii’s and Teddy’s stories of their own lives. Nimkii explains that thunderbirds “speak in thunder” and “fight Mishi-bizhiw and the horned serpents” (154-155; Fig 3): these creatures carry emotional weight for her, and become associated with her broader fears and hopes. Where the trauma she has suffered is too great to consider within her reality, the Mishi-bizhiw and Giizhogokwe stand in symbolical for threats against her (Fig. 3).

When she and Teddy are taken from their kin, she draws the Mishi-bizhiw as a threat instead of human figures (Fig. 4); when she attempts to rescue her brother, she draws the serpent Giizhogokwe in the shadows of the houses (Fig. 5).

These creatures strengthen the sinister tone associated with the foster care system just as the thunderbird represents protection and strength. The thunderbird is a constant sign of support that extends beyond the figurative landscape, as a protection against both the creatures it faces in Nimkii’s mother’s stories, and the colonial structures she faces in her everyday life.

In Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada, Chelsea Vowel argues that Indigenous social organizations have historically centred on spirituality, kinship, and land-based knowledge. Canada’s child-welfare system, she states, led to “thousands of Indigenous peoples being raised without their culture” (183, 187). The settler state has worked to assimilate Indigenous peoples by disrupting communities, and removing children from families is one way that Indigenous children lose their culture.

In this context, thunderbird stories are not only a memento of Nimkii’s mother and a symbol of her Anishinaabe heritage. Thunderbirds demonstrate what importance traditional knowledges continue to have into the 20th (and 21st) century. They are a part of oral Indigenous culture, and a step towards renewing historic Indigenous perspectives.

As well, the events of recent history can stand alongside these beliefs to create a more nuanced picture of Indigenous legacies. Nimkii keeps her memories close to her, both in her thoughts and externally, in the background spaces around her, and through the activism she dedicates time and energy to. The drive that leads Nimkii to describe her past and to hold onto the thunderbird also motivates her to protest against the presence of child services on the reserve. As part of a blockade, she strives to protect a new generation of children in her community from the struggles she and many others faced.

Akiwenzie-Damm et al. draw on the symbol of strength one last time on the final page of the comic, where thunderbirds soar through the air as a great force behind human Anishinaabe activists (Fig. 6).

The thunderbirds signify the survival of a people despite violence against their cultures. Though the community remembers the trauma, the thunderbirds show that it is used to build relationships and Indigenous resistance, where past and present, loss and renewal reveal themselves equally in a story that promises to continue.

Works Cited

Akiwenzie-Damm, Kateri, et al. “Nimkii.” This Place: 150 Years Retold. HighWater Press, 2019, pp. 138-164. ProQuest, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.uwinnipeg.idm.oclc.org/lib/uwinnipeg/reader.action?docID=5760003

Vowel, Chelsea. “Our Stolen Generations: The Sixties Scoop and Millennial Scoops.” Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. HighWater Press, 2016, pp. 158-165.

back to top

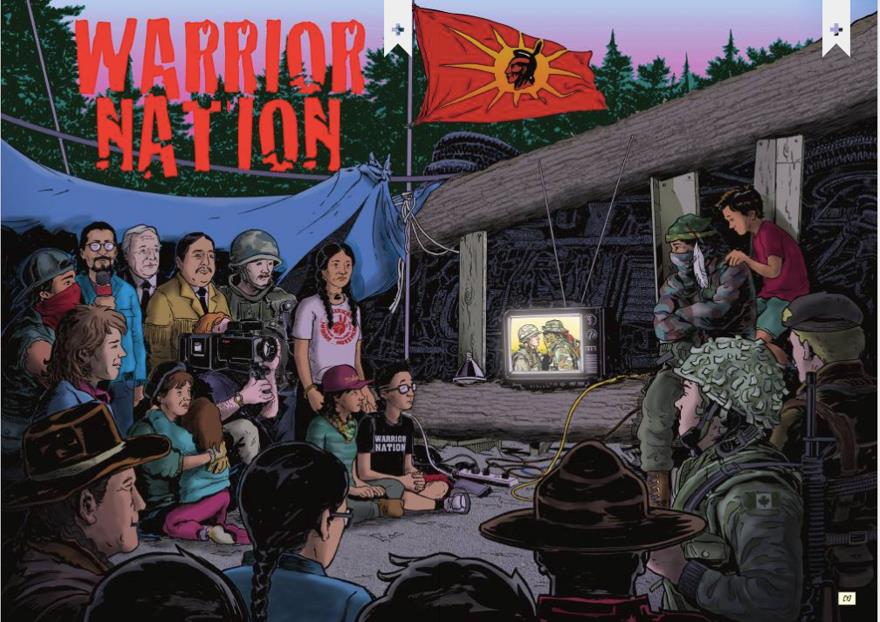

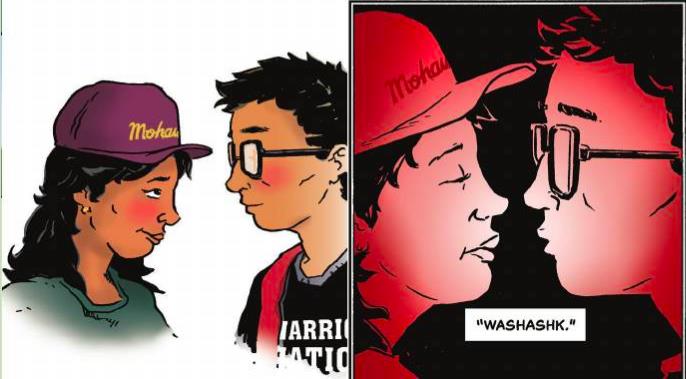

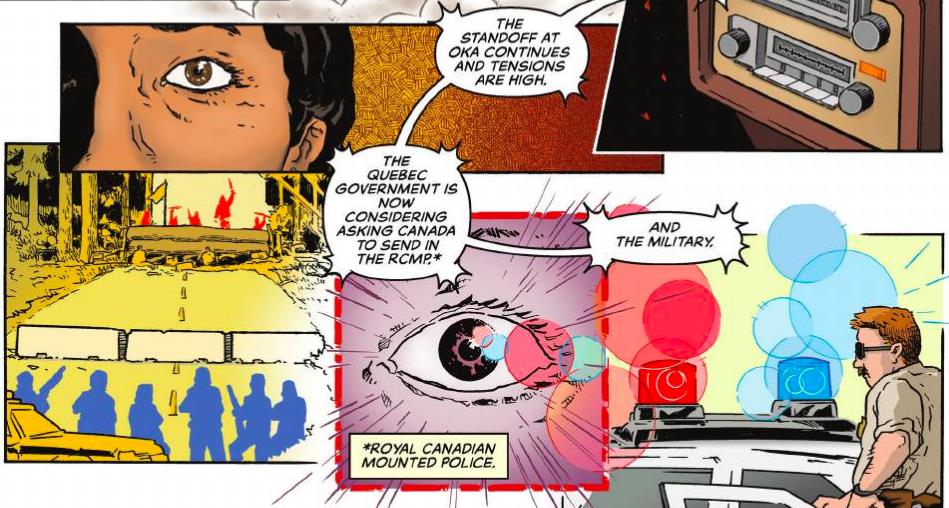

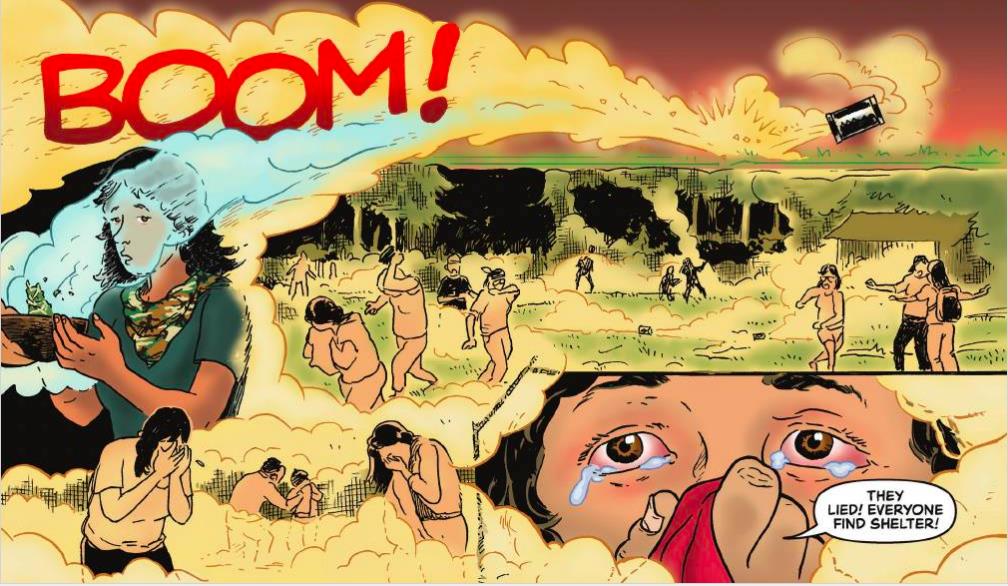

“Warrior Nation”: A Love Story

Alexander Lucy, MA in Cultural Studies

October 30, 2019

How to cite this blog post in MLA 8:

Lucy, Alexander. ““Warrior Nation”: A Love Story.” One Book UW, University of Winnipeg, 12 Nov. 2019, https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/1b19/the-book/reading-this-place.html.

Overview