AC57 Schedule – Saturday, October 18

The 57th Algonquian Conference will feature four rooms with concurrent sessions that will appeal to academics and community members alike!

Tiered registration to eliminate financial barriers to participation!

Feast and Celebration featuring local Indigenous entertainers and Indigenous languages, and the honouring of UWinnipeg's first cohort from UWinnipeg's innovative Teaching Indigenous Languages for Vitality certificate program.

Program

Sessions take place in four rooms in Centennial Hall: 3C00, 3C01, 4C40 and 4C60

Venue: 3C00

Event Time: 9:00 a.m.–10:15 a.m.

Presenters:

- A. Boulanger

- M. Day-Osborne

- V. Demontigny

- S. Neff

- P. Ningewance

- G. Welburn

- Moderataor: R. Littlebear

Event Time: 10:30 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Presenters:

- H. Souter

- K. Pyle

- J. Dormer

- D. McCreery

- G. Welburn

- M. Kolodka

- D. Delorme

- M. Patterson

- C. Leeming

- R. Dejarlais

- and more

Event Time: 11:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Paul L.A.H. Chartrand, I.P.C. (Indigenous Peoples' Counsel) of Canada's Indigenous Bar Association, is one of twelve children in the family of a Metis trapper, fisherman and carpenter from St.Laurent, along Lake Manitoba.

His elementary and high school education were with the local Franciscan missionary nuns in St.Laurent, which was an historic mission to serve the First Nation and Metis communities of the region. A graduate of the University of Winnipeg in 1974, he later earned law degrees in Australia and Canada and spent a career as a law professor and advisor on the subject of state-indigenous relations.

He organised the first Metis Languages conference in Winnipeg in 1985 where participants identified four languages. He has made a range of proposals to government bodies for the retention of Metis and other languages. [131]

Abstract

This presentation will provide commentaries on the French Michif as spoken in St. Laurent Manitoba since the 1940s by a native speaker who is not a linguist but a retired law professor with a keen interest in the language.

In addition to examples of the pronunciations, and flexible and dynamic expressions in the language, references will include the mixed and shifting cultural and social values of the community and of Canadian society; examples of local stories and humour; as well as the speaker's attempts to promote the language since the first Michif Language Conference in Winnipeg in 1985, including a publication on the Metis National Anthem composed in 1815 by Pierrich Falcon, an ancestor of local families. He will mention some of his proposals for effective language retention approaches.

Some of the more puzzling aspects of the language include words, songs and names of unknown origin. Might someone in the audience be able to help?

Event Time: 12:00–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Derrick M. Nault

Abstract:

This paper examines two non-Indigenous allies of the Métis Nation: Honoré Jaxon and André Nault. It asks why Jaxon, a settler from Ontario who briefly served as Louis Riel’s secretary during the 1885 Northwest Resistance, is remembered more prominently in Canadian historiography than Nault, the son of settlers from Quebec, a captain in the provisional government during the Red River Resistance, and a lifelong supporter of Métis causes. Jaxon played only a minor role in 1885 and spent much of his later life in the United States. Nault, by contrast, was nearly killed by Canadian soldiers for siding with Riel in 1869–70, was an active member of the Union Nationale Saint-Joseph du Manitoba, and lived among the Métis until his death in 1924. He was also once honoured by the Métis of Manitoba, though memory of him has since faded. Yet it is Jaxon who has attracted the attention of historians and appears in a dedicated Wikipedia entry. What explains Jaxon’s memorability over Nault’s?

The present study addresses this question using Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s theory of historical silencing, which holds that power shapes not only what is remembered but how narratives are produced, which voices are amplified, and which are erased (Trouillot, 1995). I also take up Kevin Bruyneel’s idea of settler memory, which describes how dominant narratives tend to sideline Indigenous presence while focusing attention on outsider figures who seem to align with settler ideals (Bruyneel, 2021). I suggest that Jaxon’s visibility owes less to the substance of his involvement than to the narrative accessibility of his life as a settler outsider who appears to “convert” to a marginalized cause. However, Nault, an insider within Métis society, challenges dominant settler narratives, contributing to his erasure in historical accounts. I recover Nault’s legacy through oral histories, newspaper accounts, and scattered archival sources.

Event Time: 1:30 p.m.–2:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Matthew Windsor (SIL) is a linguist working for Mishamikoweesh in Kingfisher Lake First Nation. He works with local speakers of Anihshininiimowin to support community-led language and culture initiatives.

Abstract:

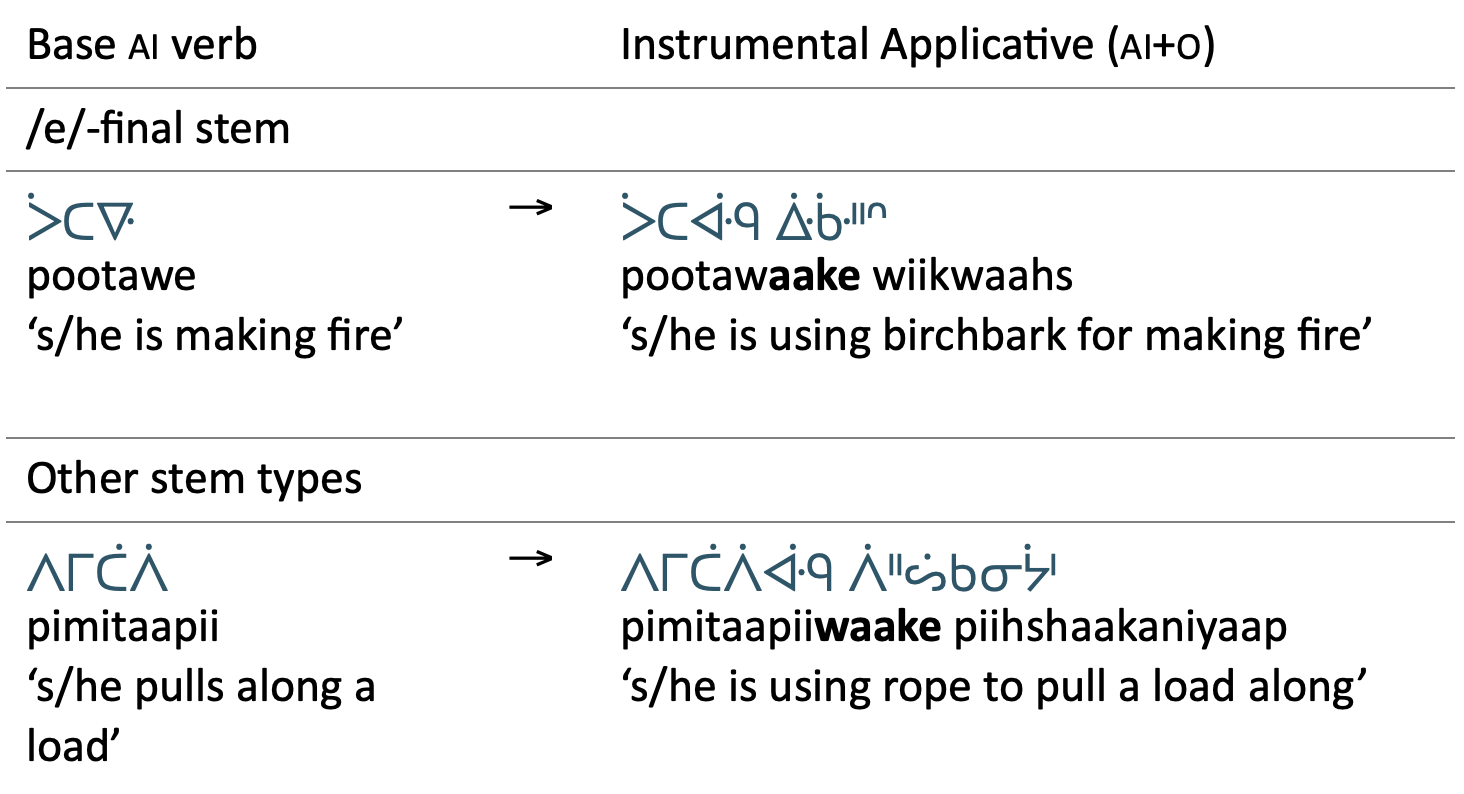

This paper presents the first full description of a dedicated instrumental applicative in Ojibwe, first noted by Todd (1970: 188). The instrumental suffix -(w)aake adds a secondary object to an ai verb, producing a new ai+o verb that means ‘use it for Ving’.

In Anihshininiimowin (Oji-Cree), this construction is fully productive. It typically indexes materials or instruments that are either topical to the discourse or else the head of a relative clause (‘wood used for making fire’).

Historically, the instrumental applicative developed from the combination of benefactive -aw and antipassive -ke, probably originating in verbs of making. This pathway appears unique among the world’s languages, though it does resemble known cases of antipassives developing into applicative markers.

Within Ojibwe, examples can be found in Southwestern, Northwestern and Algonquin (Pikogan) dialects. Cognate instrumental suffixes occur in Swampy Cree, Innu, and Naskapi. Functional equivalents also appear in a few Algonquian languages, such as Meskwaki and Old Nipissing Algonquin.

This work is part of a larger project to document Anihshininiimowin being carried out in Kingfisher Lake First Nation by a local indigenous organization, Mishamikoweesh corp.

References

Todd, Evelyn. 1970. A grammar of the Ojibwa language: The Severn dialect. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (PhD Thesis).

Event Time: 2:00 p.m.–2:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Marcella Jurotich

Abstract:

VTA verbs in the third person alternate between the direct and inverse form, as determined by the obviation status of the verbal arguments (Valentine, 2001). This study targets the factors that motivate the use of the inverse form in Border Lakes Ojibwe, specifically examining the relationship between the patient being in focus and the patient being proximate. Despite the availability of both the direct and inverse forms, data from corpus research observes that the inverse form is less common than the direct (Sullivan, 2016). Many factors impact the obviation status of a noun, such as animacy, discourse status, and information structure (Valentine, 2001). However, the exact effect of those factors on the obviation status of a noun, and thus on the use of the direct and inverse forms, remains unclear. Previous research by Dahlstrom (2014) indicates that a noun that is in focus or is a topic is not required to be proximate. This study presents data gathered through fieldwork on Ojibwe suggesting, however, that there is a preference for a focused noun to be proximate. Data indicate that the inverse form is at times more acceptable than the direct form when the patient is focused. Indeed, sentences in the direct form were corrected to the inverse form if the patient was focused in the preceding sentence. The results of this study provide further information on conditions motivating the use of the inverse, supporting teaching efforts of these complex constructions that are unfamiliar to learners and difficult to teach.

References

Dahlstrom, A. (2014). Obviation and information structure in Meskwaki. In Forty-sixth Algonquian Conference.

Sullivan, M. (2016). Making statements in Ojibwe: A survey of word order in spontaneous sentences. In Papers of the forty-fourth Algonquian conference (pp. 329-347). SUNY Press.

Valentine, R. (2001). Nishnaabemwin reference grammar. University of Toronto Press.

Event Time: 2:30 p.m.–3:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Katherine Tu

Abstract:

Certain dialects of Anishinaabemowin like Border Lakes Ojibwe (BLO) have two homophonous preverbs: a past tense preverb gii’- (note the glottal stop) and another preverb gii-, roughly meaning ‘when’ or ‘during’. A sentence like Chaan gii’-izhaa gii-gimiwaninig ‘Chaan went out when it was raining’ produces a past tense interpretation only because of gii’- prefixing izhaa; removing gii’- changes the interpretation to the present tense, i.e. Chaan izhaa gii-gimiwaninig ‘Chaan goes out when it’s raining’. Complicating the picture are preverbs gaa-, a relativizer, and gaa’-, the changed form of past gii’-. Because gii’- and gaa’- are related in this way, and building from Pentland’s (2005) hypothesis that gaa- comes from Proto-Algonquin *ki·w → *ki·, changed *ka· ‘around, about’, it may be tempting to assume that gii- and gaa- are also related by initial change. However, analysis of the data, sentences and grammaticality judgements collected from a native speaker of BLO, implies that gii- takes the tense of the matrix clause, rather than signifying relative past tense as suggested in Rhodes (1979) or completive aspect as in Fairbanks (2012). Findings from Algonquinists such as Johns (1982), Pagotto (1980), and Clarke et al. (1993) on the preverb gaa- (and the difference between it and gaa’-) are not applicable to gii-, further disproving their relatedness through initial change. There is a clear relationship between past tense gii’- and its changed form gaa’-, but the same cannot be said for gii- and gaa-.

References

Clarke, Sandra, Marguerite Mackenzie & Deborah James. (1993). ‘Preverb Usage in Cree/Montagnais/ Naskapi’. In Algonquian Papers - Archive, 24. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/638

Fairbanks, B. (2012). ‘The Ojibwe Changed Conjunct Verb as Completive Aspect’. In Algonquian Papers - Archive, 44. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/2317

Johns, Alana. (1982). ‘A Unified Analysis of Relative Clauses and Questions in Rainy River Ojibwa’. In Algo- nquian Papers - Archive, 13. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/814

Pagotto, Louise. (1980.) ‘On Complementizer Adjuncts in the Rapid Lake Dialect of Algonquin’. In Algo- nquian Papers - Archive, 11. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/787

Pentland, David H. (2005.) ‘Preverbs and Particles in Algonquian’. In Algonquian Papers - Archive, 36. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/363

Rhodes, Richard A. (1979.) ‘Some aspects of Ojibwa discourse’. In Algonquian Papers - Archive, 10. Retrieved from https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/754

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- D. Lothian

- D. Torkorno

- A. Fay

Event Time: 4:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Amy Dahlstrom

Event Time: 5:00 p.m.–7:00 p.m.

Venue: 3C01

Event Time: 10:30 a.m.–11:00 a.m.

Presenters

- Robert E. Lewis Jr. (“dokmegizhek”) is an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. He is a Potawatomi language teacher and an advocate for the Potawatomi language and the Potawatomi Confederacy. He works as the curriculum and instruction manager in the Language and Culture Department at the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. He is secretary-treasurer and on the board of Bodwéwadmimwen Ėthë ték (The Center for Potawatomi Language), a Wisconsin-based nonprofit organization that seeks to preserve and promote the use of the Potawatomi language. Robert conducts research as an independent researcher.

Abstract

Variation in the inverse in the conjunct order in Potawatomi

This paper presents a comparison of the conjunct transitive animate verb conjugations in Johnston Lykins’ and Maurice Gailland’s translations of the Gospel According to Matthew into the Potawatomi language (Lykins 1844; Gailland n.d.) and analyzes their use of the inverse marker. This paper uses the version of the translations that appear on Smokey McKinney’s website (McKinney 1997).

The two translations were compared by first copying the same verse and McKinney’s English translation. I then identified all instances of a transitive animate verb conjugated in the conjunct order. There are approximately 181 instances.

The most striking finding is that Lykins’ translation makes more use of the inverse plus an inflectional suffix (e.g. Te'pe'nmukwiIn ‘the Lord thy God’ (Lykins 1844: Matt 4:7)) compared to Gailland (n.d.) and Hockett (1939, 1948). Meanwhile, Gailland’s translation makes use of portmanteau morphs (e.g. Tepenimug ‘the Lord thy God’ (Gailland n.d.: Matt 4:7)), on par with Hockett (1939, 1948). These findings are in line with Oxford (2023)’s predictions for the inverse cross-linguistically – the inverse is used for combination of 3obv>3 as well as 3>2pl and 3>2sg. Furthermore, contra Neely (2024)’s claims for the modern day equivalents, Lykins’ inverse use is clearly not a passive, as there are instances of it with third person subjects (e.g. kikane' ke'ko e'ne'nmukwiIn, “thy brother hath ought against thee” (Lykins 1844: Matt 5:23)). These findings suggest that the inverse was used more widely in the conjunct order in Potawatomi than Charles Hockett’s often cited documentation suggests (Hockett 1939).

Selected References

Buszard-Welcher, Laura. 2001. Can the Web Help Save My Language? In The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Gailland, S.J., Maurice. n.d. Gospels of Sundays and Feasts in the Potawatomi Language, MIS 3.0106, NA 7. St. Mary’s and Sugar Creek Missions. Jesuit Archives & Research Center, St. Louis, Missouri, May 23, 2025.

Hockett, Charles. 1939. The Potawatomi Language. Yale University.

Lykins, Johnston. 1844. The Gospel According to Matthew and the Acts of the Apostles; Translated into the Putawatomie Language. William C Buck, Printer. Louisville, KY.

McKinney, Smokey. 1997. Smokey McKinney’s Prairie Band Potawatomi Web. https://www.kansasheritage.org/PBP/homepage.html

Neely, Justin. 2024. Paper presented at the Potawatomi VTA Conjunct and changes to this system. First Americans Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.

Oxford, Will. 2023. The Algonquian Inverse. Oxford Studies of Endangered Languages, Oxford University Press.

Event Time: 11:00 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Presenters:

- Amy Dahlstrom - investigates morphosyntax and information structure in Algonquian, especially Meskwaki and Plains Cree. Her research combines elicted data with analysis of narrative texts; textual attestations are particularly important for understanding topic and focus relations in languages with flexible word order, and for understanding the role played by obviation, the discourse-based opposition within third person. She has edited and translated portions of a remarkable corpus of texts written in the Meskwaki syllabary by monolingual speakers in the early 20th century, making them available both to scholars and to members of the community who no longer read the traditional syllabary.

Abstract:

Background: A striking feature of Algonquian languages is the relationship between a relative root on the verb and its associated oblique argument. In (1) the Meskwaki locative relative root tan-/taši– appears as a preverb; ayo·hi ‘here’ is the oblique. (Data from early 20th century texts by monolingual speakers.)

(1) ayo·hi ki·htaši–wi·tamo·ne

ayo·hi ke-i·h-taši–wi·tamaw-ene

here 2-fut-{there}–tell.obj.about.obj2-1>2/ind

‘I will explain it to you here.’

Relative roots generally exhibit a one-to-one correspondence with overt obliques, as in (1). Instances where a relative root seems to appear alone are often headless relative clauses (conjunct participles), where the understood head is coreferential to the oblique argument of the lower verb. (2) contains the relative root for manner, in-/iši– :

(2) wi·hiši–kekeni–ki·šikiya·ke

ic-wi·h-iši–kekeni–ki·šiki-ya·ke

ic-fut-{thus}–quickly–grow.up-1p/part/obl

‘the way for us to grow up quickly’

[ic = initial change; part = conjunct participle; obl = oblique head of relative clause]

Problem: It is possible for two tokens of a relative root to appear with no overt oblique:

(3) i·nikohi e·ši–aka·wa·nenako·we wi·hišawiye·kwe.

i·ni=kohi ic-iši–aka·wa·n-enako·we ic-wi·h-išawi-ye·kwe.

that=certainly ic-{thus}–want-1>2p/part/obl ic-fut-do.{thus}-2p/part/obl

‘That is just what I want you to do.’

[equational sentence with zero copula]

Claim: Such constructions indicate a long distance relationship between the understood head and the clause in which the head functions as an oblique argument. The extra instance of the relative root indicates the path to follow to find the verb requiring the oblique.

Community relevance: a deeper understanding of the uniquely Algonquian phenomenon of relative roots.

Event Time: 11:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Arden Ogg

- Aaron Fay

Abstract:

30 years apart in their first encounters with Leonard Bloomfield’s unpublished third collection of texts from Sweetgrass, linguist Arden Ogg and software engineer Aaron Fay became unexpected partners in bringing the 1925 text collection first into the 21st century, and then into welcoming hands at Sweetgrass First Nation. At a July 2025 Cultural Camp hosted by the band, a print copy of the manuscript was presented in ceremony to Sweetgrass Knowledge Keeper and Medicine Man Wes Fineday, on behalf of the band. Elder Fineday is a direct descendant of one original storyteller, and was, in his youth, a personal acquaintance of several others.

The evolution of the texts from pencilled syllabics to the freshly printed SRO with parallel Cree and English (now customary for Plains Cree texts), is a story in itself. It includes a genealogy of scholars and scholarship, safeguarding the original manuscript at the APS in Philadelphia, while concurrently, in Winnipeg, the texts were quietly inched forward through rapidly evolving generations of technology, as though in preparation for this very moment in 2025.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Aaron Fay

Abstract:

Aaron Fay is a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta and will be demonstrating how to use the kiyânaw Platform, a suite of tools designed by language learners for language revitalization. At the core of this platform is kiyânaw Transcribe, a tool designed for online, multiplayer transcribing. But also within the platform lies the ability to search for words and phrases as an intermediate learner to better understand their use in-context and spoken by the original speaker. For example, many languages have words that, depending on context, have different meanings, or might be said in different ways (think about "until" or "without"). Lacking long-term exposure to the language or even study, determining how to use more complex words and phrases can be a challenging task. The kiyânaw Platform aims to tackle this challenge by providing learner-directed, in-context learning centred around a searchable database of words and phrases, powered by transcription as well as our (upcoming) mobile app.

Event Time: 1:30 p.m.–2:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Antti Arppe

- Felipe Bañados Schwerter

- Rose Makinaw

Abstract:

êkosi ê-nêhiyawi-pîkiskwêcik maskwacîsihk – Towards a Spoken Dictionary of Maskwacîs Cree – Update

Since 2014, Miyo Wahkohtowin Education (Maskwacîs, Alberta), and since 2016, its successor Maskwacîs Education Schools Commission (MESC: an amalgamation of the school boards of all four Cree First Nations in Maskwacîs), and Alberta Language Technology Lab (ALTLab) have worked together to document Plains Cree (nêhiyawêwin) as it is spoken in Maskwacîs, and integrate this into various language technological digital tools.

As many as 36 speakers participated in the over 300 two-hour elicitation sessions in 2014-2018, which on the ALTLab side involved approximately 20 academics, from undergraduate students to faculty members. Altogether, the elicited new words and example sentences amount to well over 20 thousand word and phrase types, and over 100 thousand individual recording tokens. As a result of on-going validation and standardization that is approaching its completion, these are made publicly available as part of both the Speech Database (https://speech-db.altlab.app/), and a web-based electronic dictionary, itwêwina (https://itwewina.altlab.app). While the Speech Database was firstly developed to support the validation and standardization of the results of such a project, it has since been expanded to include content from other Cree dialects (from môskwacîshk) and synthesizations, as well as other Indigenous languages in Canada (Tsuut'ina, Stoney Nakoda).

We will present samples of the different types of Maskwacîs Cree content as well as demonstrate the newest functionalities of the Speech Database, including search by RapidWords semantic domains. In addition, we will convey some key general experiences gained over the course of this project.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Richard A. Rhodes is professor emeritus at University of California, Berkeley. He spent much of his career studying Ojibwe, especially the Odawa dialect. He has also contributed significantly to the documentation of other endangered languages, including Michif and the Mixe-Zoquean language Sayula Popoluca. The focus of his work has ranged from morphology and descriptive syntax to lexical semantics and lexicography. Currently he is working on historical linguistic questions in Algonquian and on 19th-century documents in Ojibwe.

Abstract:

The Cree dialect continuum stretches from Alberta to Labrador. It comprises eight dialects, from West to East: Plains, Woods, West Swampy, East Swampy/Moose, Atikamekw, East, Naskapi, and Innu Aimun. Plains Cree is the most studied variety and is generally used to stand in for the whole family in comparative Algonquian (e.g. Bloomfield 1946, Pentland 2023). Since the family is, for the most part, phonologically conservative, the fact that Plains Cree is not Proto-Cree is only of minor consequence for the reconstruction of Proto-Algonquian. But granting Plains Cree a privileged status creates a distorted of dialect relations within the family. In this paper we will examine the phonological history of the Cree family from Proto-Algonquian to Proto-Cree to current dialects. We will show that the long-held view that Cree dialects should be classified primarily on the basis of palatalization and the reflexes of PA *r (Rhodes & Todd 1972, Wolfart 1973) is mistaken. A closer look reveals that the deepest divisions are reflected in the development of sibilants and sibilant clusters. As shown by the Atikamekw reflexes (Beland, 1978, Brousseau, 2024), Proto-Cree retained a wide range of contrasts in sibilants that is completely obscured in Plains Cree.

PA s ns hs ʔs š nš hš ʔš

Proto Cree s hs hs ss š hš hš šš

Atikamekw s ss ss ss š šš šš šš

Plains Cree s s s s s s s s

The fact that all varieties other than Atikamekw share the development h[sib] > [sib], indicates that Atikamekw is the first to split off. The next splits are defined by the palatalization of k before front vowels and by the merger of Proto-Cree *š and *s. The former defines an intermediate dialect that yields modern East, Naskapi, and Innu, which we will call Eastern Cree. The latter is found peripherally in modern Plains, Woods, and West Swampy, and in Naskapi and Innu Aimun. The one variety that does not share either innovation yields East Swampy /Moose Cree. Eastern Cree varieties develop sequences involving hC differently. Outside of Plains and Woods, Cree varieties split in the development of Proto-Cree *r. Almost all other phonological innovations cross dialect boundaries: mergers of Proto-Cree *e·(with (*i· or *a·), the reflexes of PA/Proto-Cree *rk, and right edge erosion. Proto-Cree retained Proto-Algonquian final vowels, as shown by East Cree animate plural, -ač < PA *-aki, because the final vowel had to still be in place when the palatalization that created Eastern Cree occurred.

The second section of the paper will reconsider the Cree contribution to our understanding of Proto-Algonquian. Five sound changes characterize the development of Cree from Proto-Algonquian. PA *ł > t, PA *Cy > C, PA *ĕ > ĭ, PA *NC > hC, PA *łk > sk, PA *ʔ > s /__C. The identification of the first member of clusters has been an issue from Bloomfield’s time. We will examine what Proto-Cree might offer to the debate. Proto-Cree shows s where Bloomfield reconstructed x as a place holder. Assuming with Goddard (1994) that x is properly reconstructed as s leads to an interesting possibility that *ʔC which yields Proto-Cree *sC might better be analyzed as PA *sC.

Lastly, we will look at the archeology. Starting with the Laurel Culture as the Cree homeland (Denny, 1992), we will trace the spread of Cree into the present locations reflects and the interrelations between that spread and the linguistic history.

References

Béland, Jean-Pierre. 1978. Atikamekw morphology and lexicon. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Berkeley.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1946. Algonquian. Linguistic structures of Native America, ed. by Harry Hoijer et al., pp. 85-129. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology 6. New York.

Brousseau, Kevin. 2024. “Preaspirated Sibilants in Proto-Cree”, paper read to The Conference on Proto-Algonquian in Honour of the late David H. Pentland, Berkeley. CA, October, 2024.

Denny, J Peter. 1992 “The entry of Algonquian language into the boreal forest.” Paper read to the Canadian Archaeological Association, London, Ont., May 1992.

Goddard, Ives. 1994. The west-to-east cline in Algonquian dialectology. Actes du 25e Congrès des Algonquinistes, ed. by William Cowan, pp. 187-211. Ottawa: Carleton University.

Pentland, David H. 2023. Proto-Algonquian Dictionary: A Historical and Comparative Dictionary of the Algonquian Languages, in 4 Volumes. Algonquian and Iroquian Linguistics 25.

Rhodes, Richard A., & Evelyn M. Todd. 1981. Subarctic Algonquian languages. Handbook of North American Indians, ed. by June Helm, v. 6: Subarctic, pp. 52-66. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Wolfart, H.C. 1973. Plains Cree: A grammatical study. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, n.s., vol. 63, part 5, Philadelphia.

Event Time: 2:30 p.m.–3:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Antti Arppe

- Felipe Bañados Schwerter

- Cameron Duval

- Arok Wolvengrey

Abstract:

itwêwina: Towards a morphologically intelligent and user-friendly on-line dictionary of Plains Cree

We will present the current state of itwêwina (URL: https://itwewina.altlab.app/), a morphologically intelligent on-line bilingual dictionary for Plains Cree (nêhiyawêwin) – English, showcasing the morphodict platform (https://github.com/UAlbertaALTLab/morphodict). This dictionary integrates a computational model of Plains Cree word-structure (Snoek et al. 2014; Harrigan et al. 2017) with the contents of a lexical database underlying nêhiyawêwin : itwêwina / Cree : Words (Wolvengrey 2001), the Maskwacîs Dictionary of Cree Words / Nehiyaw Pîkiskweninisa (Maskwachees Cultural College 2009) and the Alberta Elders Cree Dictionary (LeClaire et al. 2002).

The Plains Cree computational morphological model allows for the linking of inflected word-forms with corresponding lexical entries, and the dynamic generation of inflectional paradigms. Moreover, we can recognize and present all linguistic content in the three currently common orthographies. Furthermore, we are able to generate and analyze simple English phrases corresponding to core inflected Cree word-forms, as their rough translations. The most recent key feature we have added is linking English search terms to WordNet senses, according to which the Cree entries have been classified, in order to resolve ambiguity.

In addition, we have continued incorporating the contents of the Spoken Dictionary of Maskwacîs Cree (Littlechild et al. 2018) and Cree recordings from other communities. Moreover, we have reconsidered the software code and user interface design to best work on mobile devices and by non-linguistic/non-academic end-users.

Besides presenting the functionalities of itwêwina, we will discuss our design decisions and their changes, in reaction to feedback from the academia and Cree communities.

REFERENCES

Harrigan, Atticus G., Katherine Schmirler, Antti Arppe, Lene Antonsen, Trond Trosterud & Arok Wolvengrey (2017). Learning from the computational modelling of Plains Cree verbs. Morphology, 27(4), 565–598.

LeClaire, Nancy, & George Cardinal, edited by Earle H. Waugh (2002). Alberta Elders' Cree Dictionary. University of Alberta Press, Edmonton.

Maskwachees Cultural College (2009). Maskwacîs Dictionary of Cree Words / Nehiyaw Pîkiskweninisa, Maskwacîs.

Mary Jean Littlechild, Louise Wildcat, Jerry Roasting, Harley Simon, Annette Lee, Arlene Makinaw, Rosie Rowan, Rose Makinaw, Kisikaw, Betty Simon, Brian Lightning, Brian Lee, Linda Oldpan, Miriam Buffalo, Debora Young, Ivy Raine, Paula Mackinaw, Norma Linda Saddleback, Renee Makinaw, Atticus Harrigan, Katherine Schmirler, Dustin Bowers, Megan Bontogon, Sarah Giesbrecht, Patricia Johnson, Timothy Mills, Jordan Lachler & Antti Arppe (2018). Towards a spoken dictionary of Maskwacîs Cree, Stabilizing Indigenous Languages Symposium (SILS), University of Lethbridge, 9 June 2018.

Snoek, Conor, Dorothy Thunder, Kaidi Lõo, Antti Arppe, Jordan Lachler, Sjur Moshagen & Trond Trosterud (2014). Modeling the Noun Morphology of Plains Cree. In: Proceedings of ComputEL: Workshop on the use of computational methods in the study of endangered languages, 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Baltimore, Maryland, 26 June 2014, 34-42. ACL Anthology.

Wolvengrey, Arok (2001). nêhiyawêwin: itwêwina / Cree Words. Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Theresa Sinclair is a retired Anishinaabemowin educator, a Language Keeper, and member of the Hollow Water First Nation and the Language Coordinator for HWFN Language Preservation Project.

- Westin Sutherland is a Heritage speaker of Anishinaabemowin. He is very passionate about preserving the language in many different ways, shapes and forms, as well as very passionate about teaching it.

- Elena "Helen" Koulidobrova is an Associate Professor in Applied Linguistics at Central Connecticut State University.

- Liliana Sánchez is a Full Professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. Together, Helen and Liliana serve as co-PIs on an NSF-funded project examining evidentiality in Indigenous languages.

Abstract:

The pandemic affected Indigenous communities in many ways, fostering community-internal practices [1] while increasing the vulnerability of Language Keepers [2],[3]. In response, several Nations partnered with non-Indigenous scholars to re-envision language reclamation [4],[5]. This report highlights an ongoing collaboration between the Language Program leadership of a Manitoba Anishinaabe Nation (Hollow Water First Nation, HWFN) and a non-Indigenous research team, at both macro (team) and micro (individual) levels.

For years, HWFN collected data on linguistic and cultural practices, showing that its distinct dialect is not well represented (e.g. “double vowel” system with voiced consonants). Land-based and language education remain separate in the curriculum, though culture and language are inseparable [6],[7]. Language use has drastically declined, and projections suggest that the Hollow Water variety may disappear within ten years. To address this crisis, HWFN partnered with linguists, data scientists, and educators to design a path for community-level language shift.

The collaboration developed procedures for reclamation and data sovereignty. Using semi-structured interviews from [8], ten different varieties of Anishinaabemowin were documented (Elder). This dataset: (i) preserves living speech and language attitudes; (ii) enables examination of generational differences in minoritized and Heritage languages [9],[10]; and (iii) provides a foundation for curricular design, since most materials overlook local varieties.

The continued need for collaborations between Indigenous Communities and settler-allies is clear. We note the collective need to make stakeholders aware of the urgent need for language preservation/reclamation, thus translating into the need for designated statutory funding as well as curricular requirements for Indigenous language education.

Event Time: 4:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- S. Thompson

- S. Henderson

Abstract:

Several significant historical events, including the numbered treaties, the Indian Act, and the Indian residential school system, transformed existing Indigenous educational models. Educational processes and policies implemented in school systems are designed to sustain the cultural, political, and social structures of Canada as a collective nation-state. These school systems reinforce dominant, settler colonial culture. Each presenter will share the research and work completed in their educational and employment contexts.

The major goal of this story sharing session is to demonstrate how land-based education models support Indigenous ways of being, doing, and knowing are reflected in their realities. This research builds on scholarship of existing Indigenous knowledge and practices of land-based pedagogy informing and being an integral component of Indigenous people and their everyday life. This research aims to counter hegemonic ideological production by decolonizing education and examining and transforming educational policies, practices, and institutions. The advocacy and research completed by both presenters reflects the Truth and Reconciliation’s Calls to Action on education.

Both Ms. Thompson and Mr. Henderson support community approaches to land-based education and work diligently to bridge the gap between the community, the school, and the home. Their work is experiential and qualitative in nature and honours Indigenous knowledge, praxis, and worldview. This session highlights practical community-driven approaches that reimagine relationships between school and land.

Venue: 4C40

Event Time: 10:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Boozhoo aaniin, my name is Westin Sutherland! I am a second language speaker of Ojibwe, and I will be walking us through all the possible steps on how to create Indigenous language dubbed media

Abstract:

Hello! This is my proposal for a workshop on how one can dub media, such as cartoons into an indigenous language. For the last decade, I’ve been working with first speakers of Ojibwe to translate and dub cartoons into the language. For the workshop, I will go through every process of taking on a project like this, and that will include all the steps like:

- How to find the media you want to be in your indigenous language. Making sure to understand that this is a non-profit project, and to classify what you create as a “non-profit fan-dubbing.”

- How to approach and work with elders in a respectful way.

- How to interpret non-indigenous stories in your language, not “translate directly.”

- How to direct voice acting with amateur experience.

- How to teach non-speakers to speak and voice act in your indigenous language.

- How to record and edit. What programs and equipment work best.

- How to get this work out there in the world. Overcoming shyness and fear when doing a project like this, which is something that goes out to a greater audience.

I will also be including video examples of my own work throughout the workshop. These are cartoons voiced by fluent Ojibwe elders, as well as friends who have been taught to say things in Ojibwe. I may also ask for audience participation and have some audience members record a short clip to show how the process is done in-person.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- John-Paul Chalykoff

Abstract:

With 15 minutes for sharing music, 10 minutes for autoethnographic arts-based research, and 5 minutes for Q&A, this performance meets presentation takes place at the intersections of education, music, and Indigenous language revitalization. It involves playing music from an album of new songs in Anishinaabemowin, coinciding with the album’s launch in October 2025.

Utilizing Indigenous autoethnography and arts-based research, autoethnographic reflections cover the process of making an album of new songs in Anishinaabemowin. These interludes provide insights on the process, including writing, recording, performance, and inspirations.

This work was envisioned to bridge the gap between academia and community. By releasing an album of songs that are meant to be accessible to families and schools, the goal is to support making connections with Anishinaabemowin beyond traditional academia. To this end, the performance concludes with applications of the album and indications for future work.

Event Time: 1:30 p.m.–2:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Dr Lorena Fontaine, Department Head, Indigenous Studies, University of Manitoba

- Gazheek Morrisseau-Sinclair, Community Learner, Technology Consultant

- Aandeg Muldrew, Assistant Professor, University of Winnipeg

- Patricia Ningewance, Assistant Professor, University of Manitoba

- Dené Sinclair, Community Educator, Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre

Abstract:

The goal of this roundtable is to discuss and create a collaborative, multi-generational, inter-related and interdisciplinary team, coming from Community and Institutional learning frameworks, to work together towards a shared goal of Indigenous language reclamation. We argue that the future of Indigenous language reclamation depends on collaborative programming, interconnected communities and innovative partnerships, creating room for solutions and engagement across all boundaries. The roundtable brings together Indigenous scholars, intergenerational relationships and community members working in Indigenous language education and programs, each delivering learning opportunities for Anishinaabemowin, as well as a shared value partnership to deliver a successful immersion camp available to both academic as well as community-based learners. Each of the panelists will reflect on the steps we can take to develop collaborative practices beyond institutional and settler geopolitical borders, on models of collaboration, on lessons learned from past experiences, and on visions for the future. Given our own backgrounds and experiences with reawakening Indigenous languages and our concentration in the Midwest, our conversations will be heavily informed by Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin) though our roundtable, but will also include other programmatic models around Swampy Cree (N Dialect) to invite wider reflections on Indigenous language revitalization globally and active audience participation.

Memorial Time: 2:30 p.m.–3:00 p.m.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Mskwaankwad Rice is a recent Linguistics PhD graduate of the University of Minnesota and is currently a Banting postdoctoral researcher at Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe University. He is from Waasaaksing First Nation and is a learner/new speaker of Nishnaabemwin (Ojibwe language) whose language reclamation work includes in-depth documentation of L1 speech.

- Claire Halpert is Associate Professor and Director of the Institute of Linguistics at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. Since 2020, she has been involved in research efforts focused on Ojibwemowin, including 2 NSF-funded projects, and works closely with the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary.

Abstract:

This talk discusses our experiences using a children’s-book-reading task with first speakers of Ojibwe, focusing in particular on I’m a Frog! (Willems 2013). Our approach is rooted in both narrative collection methods (eg. Berman and Slobin 1994) and storyboard techniques for targeting specific grammatical constructions (Burton and Matthewson 2015). Our task begins with spontaneous/unelicited narration like traditional methods, but speakers are asked to imagine that they are reading the book in Ojibwe to children, rather than simply narrating. After 1-2 read-throughs, the researcher follows up with the speaker page-by-page. This method achieves multiple ends. First, speakers find it a more natural task than storyboarding, helping them acclimate to linguistic research. Speakers respond to the prompt and the artwork by offering rich descriptions of details in the drawings, meta-commentary on the story, and other elements of reading to children. The narratives that speakers give us are thus rich spontaneous texts, which are valuable for language documentation. Finally, the story allows targeted investigation of individual/stage-level distinctions, change-of-state, and verbs of seeming and pretending; other Willems books afford targeted investigations of other hard-to-elicit constructions. We therefore advocate for this method, and these particular texts, as one that can yield valuable documentary and analytical results. More importantly, this task is effective at establishing new research relationships and could be undertaken by non-linguists beginning language work with family or community members. To that end, we describe our next steps: work-in-progress with an Ojibwe children’s book artist to create culturally-specific materials for story tasks.

References

Berman, Ruth and Dan Slobin. 1994. Relating Events in Narratives: A Crosslinguistic Developmental Study. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Burton, Strang and Lisa Matthewson. 2015. Targeted Construction Storyboards in Semantic Fieldwork. In Methodologies in Semantic Fieldwork.

Mayer, Mercer. 1969. Frog, where are you?

Willems, Mo. 2013. I’m a Frog! Hyperion Books.

Event Time: 4:00 p.m.–4:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Abiodun Samuel Ibikunle is a doctoral student in the Department of Linguistics at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on phonetics, phonology, and African languages, with particular interests in vowel harmony, loanword adaptation, and the phonology–morphology interface. Prior to his doctoral studies, he served as Lecturer in Linguistics at Adekunle Ajasin University, Nigeria, where he taught a wide range of courses in phonology and phonetics. He has presented his work at international conferences, including the Annual Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL), and has published on diverse aspects of African phonology.

Abstract:

This study investigates the phonological adaptation of English personal names into Border Lakes Ojibwe, revealing systematic processes by which speakers integrate foreign names into their native sound system. Drawing on a dataset of 60 elicited name adaptations from a fluent Ojibwe speaker, the research identifies four consistent strategies: segment substitution, vowel insertion (epenthesis), syllable restructuring, and diphthong simplification. For instance, English segments absent in Ojibwe, such as [f], [v], [l], and [r], are consistently replaced with phonologically similar alternatives ([p], [b], [n], [w]), while vowel insertion is used to repair illicit consonant clusters, preserving Ojibwe’s preferred CV/CVC syllable structure. Diphthongs like [oʊ] and [eɪ] are resolved through monophthongization, often involving compensatory lengthening. English stress is also adjusted to fit the native stress pattern of Ojibwe.

These adaptations are analyzed using Optimality Theory, where we show that there is a preference for changing sounds to conform to the sound patterns of Ojibwe are prioritized over maintaining the sound patterns of English. The findings underscore that loanword adaptation in Ojibwe is rule-governed and reflects deep speaker intuitions about phonological structure.

Beyond theoretical implications for loanword phonology and constraint interaction, this study contributes to Indigenous language documentation and revitalization pedagogy. Given that names are among the most frequently used lexical items in social interaction, understanding their adapted forms offers both a pedagogical entry point and a linguistic record of contact-driven change. Ultimately, these name adaptations serve as evidence of Ojibwe’s dynamic resilience in integrating external elements while maintaining phonological coherence.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Vivian Nash is a member of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and a Linguistics PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Abstract:

This paper examines the differences in usage between gye and miinwaa (both meaning ‘and’) as they have been used by first language speakers of Ojibwe. Currently, for some language classes, both are introduced as interchangeable, used to conjoin both sentences and nouns. This project aims to provide nuance to these teachings, allowing language learners to access language which more closely resembles that of our first-language speakers. Previous descriptions of Ojibwe detail some differences, including the use of miinwaa for ‘again’ or ‘more’, and the use of gye alongside emphatic pronouns (Valentine 2001; Fairbanks 2016). I discuss here the frequency of these uses, and I examine the frequency of conjunction of nominals, events, and mixed types by gye and miinwaa. Data comes from a set of narratives by Alice King (King, Rogers & Nichols 1985). I catalogued each use of gye and miinwaa, including the categories of constituents they conjoined. In these texts, miinwaa is used more than gye, and gye is very often used alongside emphatic pronouns (niin ‘I’, wiin ‘he/she’ etc). In addition, miinwaa was used to coordinate a nominal with a clause. I will discuss additional differences between the two words, as well as how this information may be applied to Ojibwe language instruction.

Fairbanks, Brendan. 2016. Ojibwe discourse markers. U of Nebraska Press.

King, Alice, Jean H. Rogers & John (John D.) Nichols. 1985. The stories of Alice King of Parry

Island. Winnipeg: Native Languages Programme, Dept. of Native Studies, University of Manitoba.

Valentine, Rand. 2001. Nishnaabemwin Reference Grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Venue: 4C60

Event Time: 10:30 a.m.–11:30 a.m.

Presenters:

A’tsimaan Language Immersion Program, Iniskim University of Lethbridge

- Annabelle Chatsis (Akaakskimaki ‘Many Metals Woman’) is the A’tsimaani Blackfoot Language Adult Immersion Program Coordinator at Iniskim University of Lethbridge. Annabelle has been with the program since 2024 and is currently involved in the revitalization of the Blackfoot Language. Annabelle is involved in ensuring that all students at the University of Lethbridge have opportunities to participate in Blackfoot immersion activities held on campus. Annabelle taught Blackfoot language for the University of Montana in 2013 for 5 years and coauthored an article, “Respecting Dialectal Variations in a Blackfoot Language Class.” She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree and a master’s in clinical social work.

- Inge Genee (Piitaakii ‘Eagle Woman’) is a professor of Linguistics at Iniskim University of Lethbridge in Alberta. Originally from the Netherlands, she has been working with Blackfoot speakers, learners and teachers to document and support the Blackfoot language for almost two decades. She is the editor of the Blackfoot Online Dictionary and the director of the Blackfoot Language Resources program and website Kiistónnoon Aiitsí’poyio’pa “We are speaking Blackfoot”. Inge is also one of the co-editors of the Papers of the Algonquian Conference.

- Mia’nistsinihkiakii (‘Sings Many Songs’) Caroline Russell is a Blackfoot language instructor at Iniskim University of Lethbridge. I currently teach Niitsiipowahsin (Blackfoot Language) classes at Iniskim. There is a decline in many Indigenous Languages across Canada, Blackfoot is one of them. At Iniskim we are working towards rematriation of Blackfoot Language. We held our first successful Blackfoot Language Immersion camp this summer, and hope to continue this every summer.

- Mary Fox's Blackfoot name is “Mia’nistsitsiiksiinaakii”. Mary inherited her maternal Blackfoot Great Grandmother’s name and her first language is Blackfoot. Mary was born and raised on the Blood Reserve/Kainai Nation. She is with the Indigenous Studies Department with the University of Lethbridge. Mary, as a First Nations Educator, and First Nations Education Cultural and Language Consultant and Advisor with over 35 years of experience is a dedicated professional who has significantly contributed to the education system. She is also a member of the Blackfoot Stand Up Headdress Women. She has a deep understanding of the cultural and linguistic contexts of First Nations communities, which informs her teaching methods and curriculum development. Mary emphasizes language immersion as a core component of educational programs; helping students to understand their cultural identity and heritage. Mary also believes that indigenous languages are the heartbeat of their respective cultures and healing sources, and key to the revival of languages to ensure that the next generations transmit them to their future children and grandchildren. Mary is also committed and dedicated to Indigenous health and justice, and Truth and Reconciliation in context with the history of Indian Residential Schools, and the impact of the “Residential School Syndrome,” and building positive relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and communities. This combination of experience, dedication, and advocacy makes her a valuable asset to the education sector.

Abstract:

In this talking circle we reflect on the first Blackfoot language adult immersion camp we organized this past summer.

The camp took place on traditional lands near the territory of the Kainai Nation. A large tipi was set up as a classroom and central gathering space. There were field trips to three other important sites as well as guest presenters at the camp.

Ten students, who had completed at least two Blackfoot language courses, took the camp for academic credit. There were also 20 spots for community members. We had three fluent speakers/Elders as teachers, plus an instructor for the credit course, and fluent speaker facilitators for each field trip. The students received some training and self-assessment before the camp and came back after the camp to do evaluations and present their projects.

We will share what we learned and hope to have a conversation with others who have organized similar place-based language activities to exchange ideas and best practices to improve the camp for next year. We are particularly interested in the following themes and questions:

- How can we ensure more actual language learning happens? What are good ways to assess learning?

- How can we better balance the differences between the various participant groups (students, community members, Elders, teachers, adults and children)?

- How can we improve student and Elder/teacher preparation and also include community members in that process?

Abstract:

What do Silent Speakers need to be successful in their language reclamation journeys? Giimooch Bizindawaad was a community pilot program inspired by the Language Block method (Fjellgren/Huss, 2019). For four months Silent Speakers, with the help of 2 facilitators & a therapist, explored the issues that have impacted their relationships with Anishinaabemowin.

Silent Speakers are sometimes referred to as “receptive bilingualists” or “understanders” who, for a variety of reasons (residential/day schools, the 60’s Scoop, relocation, trauma, etc.), had their relationship with Anishinaabemowin interrupted, often at a young age. They still understand the language but may no longer speak it, or only speak under certain conditions. Often they compare their fluency and language ability to the generations before them, and don’t see themselves as speakers today.

We consider Silent Speakers to still be first speakers of Anishinaabemowin, no matter their current relationship with their language. This means they are not language learners and are the closest to regaining oral fluency. We believe if they are provided the right spaces and support - they will come to see themselves as speakers again. Trust, comfort, and relationship are key to this process.

Giimooch Bizindawaad participants and facilitators will share their experiences of healing and rediscovering identity through language reclamation. The inspiration for the program, its development, and the unique needs of Silent Speakers will be discussed with a Q & A to follow.

To date, Silent Speakers have been largely ignored (or misunderstood) in the language revitalization community. We hope to bring awareness to their unique needs, share methodology, and make space for their voices.

Event Time: 1:30 p.m.–2:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Kory Wibberly

Abstract:

The goal of this project is to produce a comprehensive and accessible glossary of Algonquianist linguistic terms, geared toward a primary audience of Unkechaug, Shinnecock, and Montauk community language learners who may not have a background in linguistics. This project is constructed in response to a recognized need for more equitable collaboration between settler linguists doing documentation work, and the Indigenous communities at the center of that work (Leonard & Haynes 2010).

Linguistic research has a fraught history of extractive practices (see Rice 2006 for discussion on ‘informants’), with many settler-scholars collecting data from Indigenous communities, but producing work only for other academics, effectively excluding the majority of Indigenous voices from conversations about their own languages. The purpose of this glossary is to help make linguistic terminology more accessible to non-linguist collaborators, so that they may engage as equal contributors in the formulation of research projects, and utilize scholarly publications to the fullest extent possible in service of their own reclamation and revitalization goals.

The final product includes a brief introduction to basic grammatical terms such as ‘subject,’ ‘object,’ and ‘predicate,’ as well as an alphabetical glossary of more specialized terms, explained in plain language, and illustrated with examples from both English and Unkechaug. Unkechaug examples are drawn primarily from Stony Brook University[1] course materials, or adapted from Stephanie Fielding’s A Modern Mohegan Dictionary (2006). The document remains in Google Doc format to limit its accessibility to the public, while also inviting commentary and collaboration from the target community with whom it has been shared.

References

Fielding, Stephanie. 2006. A modern Mohegan dictionary. The Mohegan Tribe.

Leonard, Wesley Y . & Erin Haynes. 2010. Making “collaboration” collaborative: An examination of perspectives that frame linguistic field research. Language Documentation & Conservation 4. 268–293.

Rice, Keren. 2006. Ethical issues in linguistic fieldwork: An overview. Journal of Academic Ethics 4. 123–155.

_________________

[1] Visit https://linguistics.stonybrook.edu/outreach/Algonquian.php for more information about ALRP at Stony Brook University.

[1] Visit https://linguistics.stonybrook.edu/outreach/Algonquian.php for more information about ALRP at Stony Brook University.

Event Time: 2:00 p.m.–3:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Conor McDonough Quinn

Abstract:

A persistent sore spot when Algonquian-speaking communities and settler-ally scholars collaborate in language reclamation is the use of academic-linguistic jargon. Sometimes questioned, more often it persists as an un(der)questioned requirement on language workers to assimilate to this academic norm, and then impose the same burden on learners. It also marginalizes expert-knowledgeable speakers not trained in these opaque terms, and intimidates teachers and learners out of engaging with many essential everyday ways that fluent speakers talk.

In this workshop, we will show how to maintain precise, learner-helpful understandings of Algonquian languages without any academic-technical jargon. We invite participants to bring their challenges related to that jargon and especially, the real language patterns it tries to label.

With 30 minutes each to get introduced to the principles of this approach, work through participant- supplied examples and prepared ones, and discuss final questions/ideas, participants will learn how to:

- detechnicalize Animate, Obviative, Conjunct, and (In)Transitive into everyday terms, through the everyday meanings they communicate

- reframe "grammar" as language patterns

- use one real-phrase example of each pattern (instead of a technical term) to refer to it for

explanations/corrections

- introduce each pattern's meaning by compairing pairs of whole words: not dissecting into prefixes/

suffixes, but instead getting to know each word-part from families of words all sharing it

Listening to community made us rethink all these relations, creating an approach we hope will bring further respect, care, and kindness into collaborative language restoration.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Wunetu Tarrant

Abstract:

Padawe: Singing in the Whales is a story written/told by my grandmother, that we have translated into our language. Utilizing cutting edge technology, we have created an immersive 3D virtual reality storytelling experience, and recreated local land and water ways to appear as they may have pre-colonial contact. To date, this is the longest form media presentation spoken in the language, and a first glimpse at what our production company aspires to accomplish. The Padawe VR presentation runs about 20mins and requires the use of a VR headset (I can provide 2 Apple Vision Pros).

The second piece of this work is a collection of the culminating video presentations created by members of our newly established language nest. This small group participated in a year long intensive workshop series where they received training in language research, documentation and media production. The goal of this program is to make available all of the resources we currently have, and create an online training program and resource archive to help accelerate language reclamation, and encourage ownership of the revitalization process as something we all can participate in. These are some of the first original works which will be used as tools for teaching the language and encouraging creative expression in our language. The collection of videos run about 20mins on a loop and may be presented on a TV screen or monitor.

Breaks

10:15 a.m. - 10:30 a.m.

Health Break

12:30 p.m. – 1:20 p.m.

Lunch in 4th Floor Buffeteria

3:00 p.m. - 3:30 p.m.

Health Break