AC57 Schedule – Friday, October 17

The 57th Algonquian Conference will feature four rooms with concurrent sessions that will appeal to academics and community members alike!

Tiered registration to eliminate financial barriers to participation!

Feast and Celebration featuring local Indigenous entertainers and Indigenous languages, and the honouring of UWinnipeg's first cohort from UWinnipeg's innovative Teaching Indigenous Languages for Vitality certificate program.

Program

Saturday, October 18 – Program

Sessions take place in four rooms in Centennial Hall: 3C00, 3C01, 4C40 and 4C60

Venue: 3C00

Event Time: 9:00 a.m.–9:30 a.m.

Presenters: TBA

Event Time: 9:30–10:30 a.m.

Presenter:

- Dr. Bernard Perley

Abstract:

Species suicide. It will not happen overnight but the prospect of human extinction should not be dismissed. In this extinction scenario, all human knowledge will exist only in the artifacts and detritus we leave behind. We have been witnessing the first stage of human extinction though the acceleration of Indigenous language silence around the globe. Documenting millennia of accrued knowledges and experiences to save what’s left before it’s gone has created countless artifacts of silent and dismembered worlds. But documentation as preservation can only do so much. Instead, documentation as a catalyst for worldmaking offers strategies for emergent vitalities for language, landscape, and community. Rather than preserve the past for the present, shifting our stance toward the future invites opportunities for bringing diverse knowledge systems and ways of being-in-the-world together. In doing so, mutually respectful and empowering coalescences can contribute to ensuring species survival. As a modest example, I share my current (in progress) cartographic imaginarium as my unauthorized worldmaking catalyst for Wolastokwi futures.

Event Time: 10:45–11:30 a.m.

Presenters:

- M. Rice

- K. Anderson

- B. Alexander

- D. Dumphy

- C. Omand

- H. Souter, Moderator

Event Time: 11:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Richard Littlebear

- Wayne Leman

- Sarah Murray

Abstract:

This paper looks at the expression of definiteness and indefiniteness in the Cheyenne language, from the perspectives of language documentation, teaching, and learning.

A definite expression is used when talking about something known or unique in the context, while an indefinite is used when talking about something new to the context. In some languages, like English, there are articles that express these categories: the English word “a” is an indefinite article and the word “the” is a definite article. These are very common words in the English language and yet in many languages, including Cheyenne, there are no direct translations of them. How are the concepts of definiteness and indefiniteness expressed in Cheyenne?

In many languages, including Cheyenne, nouns appear without articles. These ‘bare nouns’ can be definite or indefinite, depending on the context. Often at the beginning of a story, when characters are first introduced, bare nouns are used. Such examples are indefinite. In other contexts, bare nouns can have a definite interpretation, as in (1), which comes from later in a story, ‘The Ant, the Bug, and the Rabbit’ by Mrs. Albert Hoffman.

(1) Naa "Náhtáme hé'tóhe," éxhesėstse hámėškona.

naa náhtáme hé'tóhe é-x-he-sėstse hámėškóna

and my.food this past-say-reportative bug

‘And "This is my food," said the bug.’

This talk will discuss further examples and contexts, drawing on existing Cheyenne materials and the first author’s judgements, while incorporating existing work and diagnostics from linguistic questionnaires. We will also discuss teaching and learning these expressions, and the relation to demonstrative expressions in Cheyenne.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters

- Antti Arppe

- Inge Genee

- Alexandra Smith: Oki, kitsiiksimatsimmohpoaawa. Niistowakao'ka Iinisskimakii. Nitsiksikaitsitapi, nimohto'too Apatohsipiikani. My Blackfoot name is Buffalo Stone Woman, I am Blackfoot and from the (northern) Piikani Nation. I recently completed my Master of Arts at Iniskim (University of Lethbridge) in August 2025. I currently work at the Peigan Board of Education Society in Piikani as the Blackfoot Curriculum Editor. I also started working at Iniskim in September as the co-instructor of the Blackfoot Language classes. I am deeply invested in the revitalization of Niitsi'powahsini (Blackfoot language) and in discovering the best ways to teach and learn the language as well.

- Conor Snoek am an anthropological linguist studying Indigenous languages of the Americas. I have worked on Plains Cree and Blackfoot, as well as Cerro Xinolatepétl, a Totonacan language spoken in Puebla State. I am interested in language histories and the evolution of meanings, as well as how languages are taught and learned.

Abstract

Niitsi’powahsini (Blackfoot) is an Algonquian language spoken by four nations within Alberta, Canada and Montana, USA, including Piikani (Brocket, AB), Kainai (Standoff, AB), Siksika (Blackfoot Nation, AB), and Aamsskaapipiikani (Blackfeet Nation, USA). The language is critically endangered, but many efforts are under way to help support, revitalize and sustain it. One gap in the available resources that can support both pedagogical and research goals is the lack of textual materials. Several Blackfoot corpora exist (Dunham 2013; Kadlec 2023; Weber 2022; Weber et al. 2023) but all of these have issues relating to accessibility and content.

This paper describes the process of curating the Blackfoot Narrative Text Corpus (BNTC) (Smith forthcoming). The BNTC is a partially linguistically analyzed corpus of Blackfoot narrative texts to support the revitalization and documentation of the language. The corpus was compiled from published Blackfoot texts. 29 texts are fully morphologically analyzed and glossed to a single list of gloss abbreviations, and 32 texts are transliterated into the modern standard orthography. After their analysis and/or transliteration the texts were integrated into the Korp corpus platform (Borin, Forsberg & Roxendal 2012). The BNTC is an open-ended, flexible, orthographically homogenous and searchable open access corpus containing more than 10,000 Blackfoot words. This corpus contributes to the broader field of Indigenous language documentation and revitalization providing a corpus of Blackfoot narrative texts with partial linguistic analysis, an accessible resource for learners, teachers and researchers of Blackfoot.

References

Borin, Lars, Markus Forsberg & Johan Roxendal. 2012. Korp - the corpus infrastructure of Språkbanken.

In Proceedings of LREC 2012, 474–478. Istanbul: ELRA. Dunham, Joel Robert William. 2013. The Blackfoot Language Database. In Papers of the 41st

Algonquian Conference, 75–80. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. Kadlec, Dominik M. 2023. A computational model of Blackfoot noun and verb morphology. Lethbridge,

AB: University of Lethbridge Master’s Thesis. https://hdl.handle.net/10133/6635.

Smith, Alexandra B. Forthcoming. Curating a corpus of Blackfoot narrative texts. Lethbridge, AB: University of Lethbridge Master’s Thesis.

Weber, Natalie. 2022. Blackfoot Words. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10. 5281/zenodo. 5774980.

Weber, Natalie, Tyler Brown, Joshua Celli, McKenzie Denham, Hailey Dykstra, Rodrigo Hernandez- Merlin, Evan Hochstein, et al. 2023. Blackfoot Words: a database of Blackfoot lexical forms. Language Resources and Evaluation 57(3). 1207–1262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10579-022- 09631-2.

Event Time: 1:30–2:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Todd Mondor, President and Vice-Chancellor

- Pavlina Radia, Provost and Vice-President, Academic

- Chantal Fiola, Assoicate Vice-President, Indigenous Engagement

- Shelley Tulloch, Chair, Anthropology

Event Time: 2–2:30 p.m.

Presenter:

Robert Shubinski, MD is an enrolled member of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians. By profession, Robert is a physician, specialized in child and adolescent psychiatry employed by Santa Barbara County. As an undergrad, he pursued majors in music and French and lived for thirteen years in France, a treasured linguistic and cultural experience. Linguistic interests include Mahican, Munsee, and other Algonquian languages. Robert is an invited member of his tribe's "Language Think Tank," however, his comments and opinions have not been officially sanctioned or vetted by any official tribal entity. Enjoys gardening with his lovely wife in Central California.

Abstract:

Every construction project has an engineer working with whatever resources are suitable and available. Building projects require plans, materials, labor, and management of regulatory hurdles. Some projects are simple, others are so complex that multiple engineers are required.

A bridge of knowledge should allow for two-way traffic, so information can flow back and forth bidirectionally.

On one side of the bridge stand the builders led by the engineering team, rooted in science, formulas, equations while balancing needs for cost control, timetables for completion, appropriate esthetics, functionality, strength, and durability.

One the other side stand the indigenous people, an admixture of people with deep seated cultural beliefs, wounds and scars from the historical trauma, and an acute awareness of the attrition of the Native way of life. No two indigenous communities are alike, and each group has disparate views about language, religion, and culture.

Algonquian linguistic and revitalization projects will require extensive structured planning involving multiple people on both sides of the river. Bridges will need plans for maintenance, repairs, and remediation of delays, disputes, and quibbles over costs. To get the job done, fundamental changes in approach are needed. Trust, the true foundation of the project, grows naturally with positive experiences.

Talking is not enough. Tribes need concrete and practical help. An entity to investigate ethical breaches, a reliable means of obtaining second opinions or quality control reviews, a unified set of rules of conduct for collaborative interactions with communities, and other ideas will be discussed in this presentation.

Event Time: 3–3:30 p.m.

Presenters

- Irene Appelbaum is a professor of linguistics at the University of Montana in Missoula. She received a PhD in philosophy and an MA in linguistics from the University of Chicago. Her research focuses on Ktunaxa language documentation and linguistics.

Abstract

Ktunaxa, like Algonquian languages, exhibits obviation. A question arising for languages exhibiting obviation is what its syntactic domain is - that is, what is the domain within which two NPs cannot both be proximate. It seems to be true for all languages exhibiting obviation that possessed nouns are obligatorily obviative and that the arguments of a transitive verb cannot both be proximate. But beyond these two domains, languages seem to differ. For example, Dahlstrom has argued for Meskwaki that obligatory obviation extends to the subject, but not the object of a complement clause, and not to the subject of adjunct clauses or into a coordinate clause (Dahlstrom, ms, pp. 3-12 – 3-18). For Ktunaxa, Dryer (1998) has argued that the whole sentence is the domain of obligatory obviation. In this talk, I re-investigate the domain of obligatory obviation in Ktunaxa, examining the framework that Dahlstrom uses for Meskwaki. Using evidence from elicitations and previously published narratives (Boas 2005), I argue that the domain of obligatory obviation in Ktunaxa patterns more closely with Dahlstrom's Meskwaki than with Dryer's Ktunaxa. I show that while obligatory obviation in Ktunaxa extends to the subject and object of a complement clause, in all other sentential contexts examined, obviation is not obligatory. In addition to showing the similarity between obviation in Ktunaxa and Meskwaki, this talk highlights the importance of investigating obviation in multiple complex sentence types to gain a better understanding of how obviation functions across the Algonquian language family.

References

Boas, Franz (2005). Kutenai Tales together with texts collected by Alexander Francis Chamberlain. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library, Digital General Collection. Originally published (1918). Bureau of American Ethnology Bull 59. D.C.

Dahlstrom, Amy. ms. Meskwaki Syntax, Chapter 3. https://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/adahlstrom/publications-2/selected-manuscripts/meskwaki-syntax-book/.

Dryer, Matthew. 1998. Obviation Across Clause Boundaries in Kutenai. In Studies in Native American Linguistics IX. John Kytle, Hangyoo Khym, and Supath Kookiattikoon, eds. Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics 22:2:33-51.

Event Time: 3:30–4 p.m.

Presenters

- Hope Trischuk is an emerging Settler-scholar and recent graduate from the University of British Columbia. She undertook a BA in linguistics, where her research focused on how linguistic research can support Indigenous language revitalization. In particular, she is passionate about bridging the gap between research and the educators and students who benefit from it. Over the past year, she has been honoured to work on the documentation of Border Lakes Ojibwe with consultant Nancy Jones. As part of ELF lab at UBC, she has been excited to develop a study exploring how to teach obviation to L2 speakers.

Abstract

The distinction between proximate and obviative nouns is an active area of investigation in the study of Algonquian languages. The obviation status of a noun is fluid and can change throughout a sentence or discourse (1; 3; 7). Many connections between semantics and obviation have been posited; particularly, research has previously suggested a relationship between obviation status and point of view (2; 5; 6). To investigate this relationship, my research tested the acceptability of obviative subjects and obviative agents of attitude verbs like ‘want’,‘think’, and ‘believe’. If proximate nouns are the preferred subject or agent of attitude verbs, it suggests that revealing the internal mental state of the subject or agent is associated with obviation status. Further, it may imply a connection between a noun’s obviation status and its status as the point of view referent — the character in a given clause with whom we are expected to empathize (4). Results from elicitations with Nancy Jones, a fluent speaker of Border Lakes Ojibwe, show a slight preference for proximate subjects of VAI and VTI attitude verbs, while both proximate and obviative agents were acceptable with VTAs. While these preferences are not definitive, the speaker's comments suggest an aversion to using an obviative subject when discussing said character’s internal mental state. As a meaning distinction is worked towards, the goal of this research is to bridge the gap between linguists and instructors to help learners understand the fundamental topic of obviation and consequently encourage confidence and natural fluency.

Event Time: 4:00 p.m.–4:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Stéphane Goyette

Abstract:

On sait que le français parlé par les métis de l’Ouest canadien (Papen 2004) possède nombre de traits syntaxiques issus de langues algonquiennes (cri et ojibwé). Le but de cette présentation est de montrer l’existence d’un autre trait d’origine algonquienne :l’utilisation de « ça » en français métis, en alternance avec « il/elle/, qui s’aligne sur le marquage de l’obviatif en cri et en ojibwé. On examinera aussi le cas de la langue koutenaï, dont le marquage obviatif ressemble singulièrement au système algonquien (Dryer 1992). Dans tous ces cas il semblerait bien que le contact langagier aurait provoqué la diffusion du marquage de l’obviatif dans différentes langues. Ceci jette un sérieux doute sur la question de savoir si, oui ou non, l’obviatif existait en proto-algonquien. La réponse serait oui, à en croire Bloomfield (1946). Mais la réponse pourrait être non, si l’obviatif s’est diffusé après la désintégration du proto-algonquien. On donnera différents exemples connus de diffusion de traits au sein de langues toutes membres d’une même famille linguistique qu’on pourrait à tort attribuer à la proto-langue. Enfin, vu que nombre de communautés dont la langue ancestrale était algonquienne cherchent aujourd’hui à ressusciter ladite langue, il n’est pas interdit de se demander si la présence de l’obviatif dans la langue vernaculaire de certaines communautés aujourd’hui ne pourrait pas (avec un appui pédagogique approprié, bien entendu) faciliter l’apprentissage de la langue ancestrale comme langue seconde (Voir Hamp 1989 pour une suggestion semblable).

Références.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1946. “Algonquian” . In Linguistic structures of Native America, sous la direction de Harry Hoijer et al. New York, Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology 6. pages 85–129.

Dryer, Matthew. 1992. “A Comparison of the Obviation Systems of Kutenai and Algonquian”. In: Papers of the Twenty-Third Algonquian Conference, 1992, sous la direction de William Cowan. Ottawa: Carleton University, pages 119-163.

Hamp, Eric P. 1989. « On signs of health and death”. In: Dorian, Nancy (Sous la direction de) Investigating obsolescence. Studies in language contraction and death. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. Pages 197-210.

Papen, Robert A. 2004 « Sur quelques aspects structuraux du français des Métis de l’Ouest canadien », dans Aidan Coveney, Marie-Anne Hintze et Carol Sanders (dir.), Variation et francophonie, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2004, pages 105-129.

Event Time: 4:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

Sauvane AGNES holds a PhD in linguistics from Paris-Sorbonne University and wrote a thesis on Algonquian morphosyntax. She works within the scope of linguistic diversity and is interested in ethnocentrism and how it colors linguistic descriptions, especially of minoritized languages. She is member of the Société de Linguistique de Paris and of the Society of Americanists, and associate member of LACITO (Languages and Cultures of Oral Tradition) and of CELTIC-BLM (Centre d’Etudes des Langues, Territoires et Identités Culturelles - Bretagne et Langues Minoritaires). She currently holds a position has Visiting Associate Professor at Rennes 2 University.

Abstract:

Dans les langues du monde, les relatives et leurs équivalents sont définies comme des propositions ayant une fonction de modifieur d’une tête substantivale. En innu-aimun, la fonction de modifieur des têtes de syntagme substantival est principalement assurée par des formes verbales à l’ordre conjonctif, qui constituent ainsi des équivalents de nos relatives. Plusieurs constructions coexistent cependant, qui paraissent difficilement se réduire à la simple dichotomie - par ailleurs discutable même en français (cf. entre autres Fuchs 1987)[1] - opposant des relatives qui seraient ‘restrictives’ - c’est-à-dire qui restreignent l’étendue de la classe d’entités désignée par l’antécédent et permettent ainsi de construire la référence de cet antécédent - et des relatives ‘non-restrictives’, qui expriment l’une des caractéristiques du référent désigné par l’antécédent, sans que cela n’intervienne dans la construction de sa référence. Inversement, la construction de certaines relatives est identique à celles de propositions complétives ou circonstancielles, comme on peut l’observer ci-dessous pour la ka + forme verbale conjonctive, analysée en a. comme une relative restrictive, en b. comme une proposition circonstancielle :

- tet.ap -u miut-iǹu ka misha -ǹ -it

au-dessus-de.placé 3Inacc boîte ObvNI Subst° gros.¬téliq ApplOBV 3CNJ

« il/elle est assis(e) sur la grande boîte » [lit : « sur (la) boîte qui est grande »] (Drapeau, 2014 : 263) - uiesh six mois ni- tatupishimueshita -kupan ka shukaitashu -ian

approximativement six-mois Pers1 avoir-tant-de-mois Dubitf+Prét Subst° être-baptisé 1sgCNJ

« Je devais avoir environ six mois quand j’ai été baptisée » (extrait de Joséphine Picard - Pessamit)

Nous proposons dans cette communication de partir de la comparaison des différentes constructions propositionnelles de l’innu traduites en français par des relatives, des complétives ou des clivées pour tâcher de saisir les paramètres pertinents dans la langue innue rendant compte de la multiplicité de ces constructions.

________________

[1] FUCHS Catherine, 1987. « Les relatives et la construction de l’interprétation », Langages, 88, p.95-127. Dans cet article, l’autrice souligne que les constructions relatives « canoniques », dont on peut éventuellement opposer des restrictives et des non-restrictives, sont de la forme « les N qui V », donc avec un antécédent pluriel défini. Les interprétations des constructions relatives dont l’antécédent est singulier ou indéfini sont alors plus variables et par conséquent moins réductibles à la stricte opposition « restrictive » versus « non-restrictive ».

Venue: 3C01

Event Time: 11:30–12 p.m.

Featuring:

- Samantha Prins is a PhD candidate in Linguistics at the University of Arizona. Their training is in language revitalization and morphosyntactic theory with a focus on North American languages and linguistics. Her current work focuses on nominal morphology in Algonquian and the intersections of linguistics and community language work.

Abstract:

Algonquian languages are notable for their abundant nominal syncretisms, where suffixes realize distinct features without corresponding distinctions in form. While these languages share a core set of inflectional features (animacy, number, and obviation), language-specific syncretisms yield varying paradigm shapes across the family (Bliss & Oxford 2017). Here, I investigate the underlying organization of nominal features and how it captures this spectrum of variation.

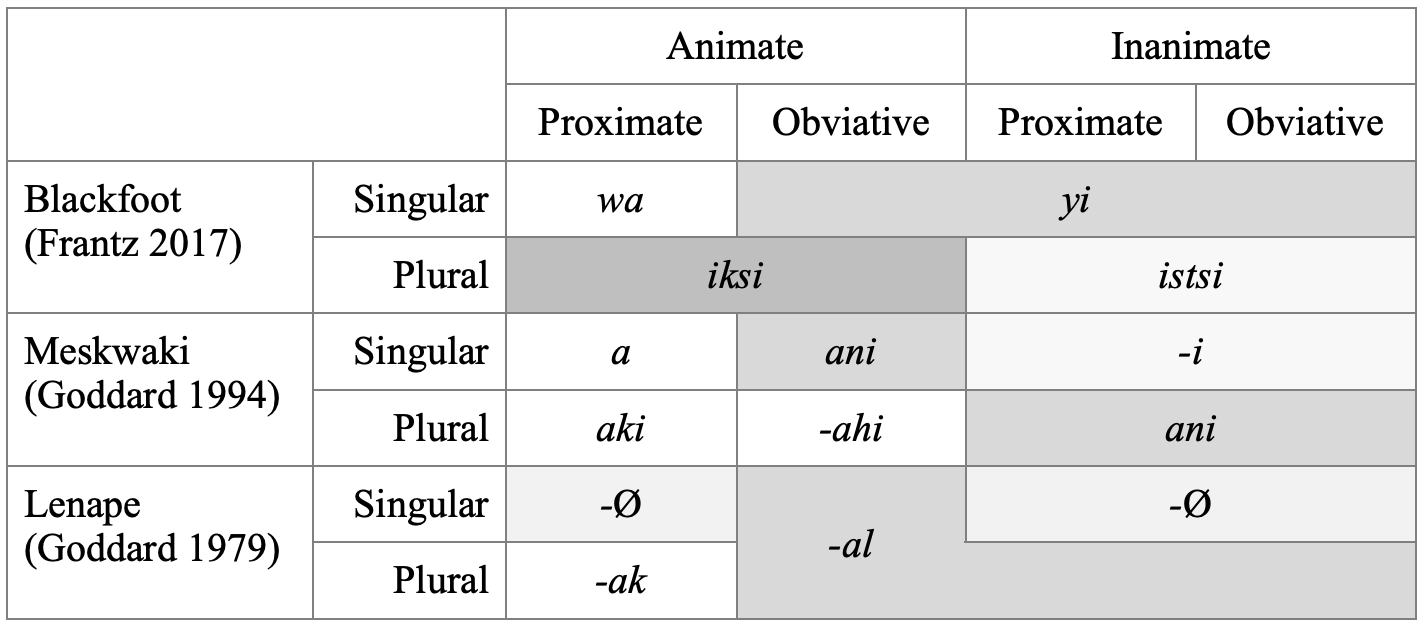

Figure 1. Selected Algonquian nominal paradigms (adapted from Bliss & Oxford 2017)

Comparing Blackfoot, Meskwaki, and Lenape (Fig. 1), for example, syncretisms vary in both scope and complexity. Nearly all Algonquian languages have an obviation syncretism for inanimates; Blackfoot extends this to animate obviative nouns, and has an additional obviation syncretism for animate plurals. Meskwaki has a diagonal syncretism, crosscutting both number and animacy categories. Lenape’s number-animacy syncretism is even more complex, extending multidirectionally across the paradigm.

Building on prior work (Bliss & Oxford 2015, 2017), these paradigms are reexamined within a Distributed Morphology framework (Halle & Marantz 1993, 1994), where syncretisms arise from underspecification and/or impoverishment of features. Following e.g., Noyer 1998, Béjar & Hall 1999, and Nevins 2011, the role of markedness is also explored. I hypothesize that variation results from language-specific relationships among features, while recurrent patterns point to deeper facts about Algonquian as a whole.

This analysis contributes to broader discussions of syncretism in Algonquian and other languages. Beyond the theorization of inflection, paradigms, and features more generally, this work is necessarily also in conversation with community-based revitalization and maintenance efforts, where analysis can be leveraged to support grounded documentation and pedagogy.

References

Béjar, Susana & Daniel Currie Hall. 1999. Marking Markedness: The Underlying Order of Diagonal Syncretisms. In Proceedings of the 1999 Eastern States Conference on Linguistics. Cornell Linguistic Circle Publications.

Bliss, Heather, & Oxford, Will. 2015. A Microparametric Approach to Syncretisms in Nominal Inflection. In Proceedings of the 33rd West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 67–76.

Bliss, Heather & Will Oxford. 2017. Patterns of Syncretism in Nominal Paradigms: A Pan-Algonquian Perspective. In Papers of the Forty-Sixth Algonquian Conference. Michigan State University Press.

Frantz, Donald. 2017. Blackfoot Grammar. 3rd ed. University of Toronto Press.

Goddard, Ives. 1979. Delaware verbal morphology: a descriptive and comparative study. New York: Garland.

Goddard, Ives. 1994. Leonard Bloomfield’s Fox lexicon. Algonquian and Iroquoian Linguistics.

Halle, Morris & Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the Pieces of Inflection. In The View from Building 20, ed. Kenneth Hale and S. Jay Keyser, 111–176.

Halle, Morris & Alec Marantz. 1994. Some Key Features of Distributed Morphology. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics, 21:275–288.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Marked Targets versus Marked Triggers and Impoverishment of the Dual. Linguistic Inquiry, 42(3):413–444.

Noyer, Rolf. 1998. Impoverishment theory and morphosyntactic markedness. In Morphology and Its Syntax, ed. Steven G. Lapointe, Diane K. Brentari, and Patrick M. Farrell, 264-285.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Will Oxford (Professor of Linguistics, University of Manitoba) studies morphology and syntax from descriptive, historical, and theoretical perspectives, often with a focus on the Algonquian languages.

Abstract:

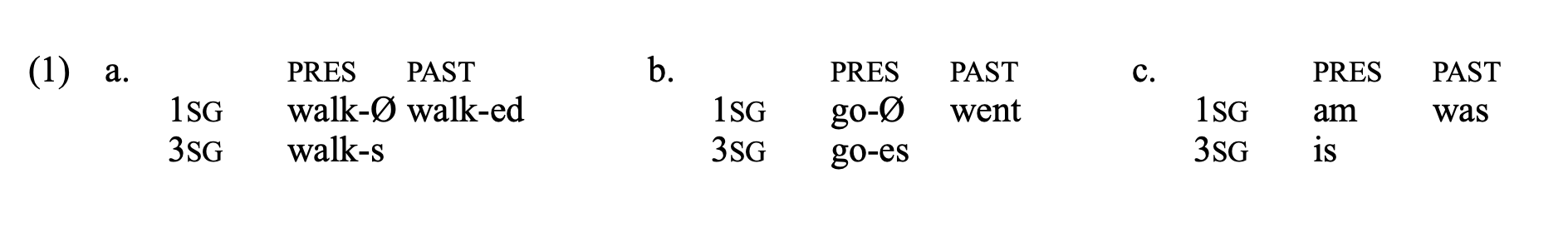

A syncretism is an instance of neutralization in a morphological paradigm. In English, for example, regular verbs with 1sg and 3sg subjects take different inflectional suffixes in the present tense (-Ø vs. -s), but in the past tense there is a syncretism: the same suffix -ed appears either way. Some syncretisms are a quirk of a particular paradigm, but our English example holds not only for regular verbs like walk, as in (1a), but also for irregular verbs like go and be, as in (1b–c). A syncretism that holds across formally distinct morphemes in this way is called a metasyncretism (Williams 1994; Bobaljik 2001; Harley 2008).

Metasyncretisms are notable because their analysis must be neither too shallow nor too deep. The English syncretism in (1a) cannot be given a shallow analysis in which it is simply a property of the suffix -ed, since this would not explain why the same syncretism recurs across formally unrelated items such as went and was. But it also cannot be given a deep analysis in which the language’s verb inflection lacks a contrast between 1sg and 3sg altogether, since that contrast is robustly manifested in present-tense forms.

This presentation will discuss the following four patterns in Algonquian inflection, each of which poses difficulties for a morphological analysis:

Central agreement inflection does not distinguish number for obviatives, even in languages that do make this distinction in peripheral agreement.

In TA forms with a 1pl argument and a second-person argument, most of the languages do not express the number of the second-person argument.

In some varieties of Ojibwe and Potawatomi, 1pl→2 forms are homophonous with X→2 forms.

The same morphology expresses animate obviative (singular) and inanimate plural in most of the languages.

It will be shown that each of these patterns is in fact a metasyncretism, a conclusion that disentangles these patterns from the hierarchy effects that occur elsewhere in the inflectional system and helps to point the way toward a more adequate analysis. While this research does not directly address community-identified needs, it is hoped that the distinction between syncretisms and hierarchy effects will be useful to anyone who is interested in more deeply understanding the internal logic of the morphological system, including researchers, teachers, and advanced learners.

References

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2001. Syncretism without paradigms: Remarks on Williams 1981, 1994. Yearbook of Morphology 2001: 53–85.

Harley, Heidi. 2008. When is a syncretism more than a syncretism? Impoverishment, metasyncretism, and underspecification. In Phi theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, ed. by Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Bejar, 251–294. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, Edwin. 1994. Remarks on lexical knowledge. Lingua 92: 7–34.

Event Time: 3:00 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- David Costa is a tribal linguist supported by the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma to work in the Myaamia Center at Miami University (Ohio), the Miami Tribe’s research and development center, where he serves as the Program Director for the Language Research Office. The Myaamia Center is a tribally funded and directed research center embedded within a 52-year relationship between the sovereign Miami Tribe of Oklahoma and Miami University. Costa has been studying the Miami-Illinois language since 1988. Originally from the San Francisco Bay Area, he now resides in Oxford, Ohio.

Abstract

All Algonquian languages have what are traditionally called ‘verbs of being’ and ‘verbs of possession’. These are verb stems, productively derived from noun stems, which are used to express general concepts of being or becoming, and of having or possessing. ‘Verbs of being’ are usually AI stems but occasionally II stems, while ‘verbs of possession’ can be either AI stems, TA stems, or occasionally TI stems. In this talk I will discuss how verbs of being and possession are formed and used in Miami-Illinois, with some discussion (as time permits) of analogous constructions in other Algonquian languages.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Jack Crabb is a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include morphology, language reclamation, and sociophonetics. He is a non-Indigenous Linguist.

Abstract:

This paper presents the first study of color in Algonquian languages and examines how traditional methods for identifying basic color terms should be rethought. Early studies on color, particularly the work of Berlin and Kay, defined ʙᴀsɪᴄ ᴄᴏʟᴏʀ ᴛᴇʀᴍs as “monolexemic” adjectives (1969:6). This does not accurately account for the vast majority of Algonquian languages, where color is most often expressed through verbs. I explored over twenty Algonquian languages using dictionaries and word lists with a focus on morphologically basic color verbs. To create a family-specific definition of basic color terms, I excluded forms that included preverbs, loanwords, finals with complex meanings, and indirect translations. This approach yielded twenty-one potential basic color verbs, with only three, ‘white,’ ‘black/dark,’ and ‘red,’ found in each language surveyed. This mirrors the findings of Berlin and Kay (1969:2) for languages with at least three colors. Other categories, such as ‘grue’ (green, blue) and ‘ochre’ (yellow, brown, orange), demonstrated considerable variation in what color(s) were represented.

In conclusion, this paper introduces the first family-level typology of color for the Algonquian languages. Future research could focus on community-informed elicitation with speakers in natural and controlled contexts, as relying solely on dictionaries and word lists restricts the depth of interpretation. Because this research depends on the translations and decisions of dictionary compilers, it may not fully capture the shades of meaning represented by each term, and is ultimately only as reliable as its sources.

(241 Words)

References:

Berlin, Brent, and Paul Kay. 1969. Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. Berkeley ; Los Angeles:

University of California Press.

Event Time: 4:00 p.m.–4:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Lucy Thomason

Abstract:

Leonard Bloomfield’s “Algonquian Sketch” (1946: 104) notes the difference between “abstract finals, which merely determine the form-class (noun, four types of verbs, or particle) and concrete finals, which add some more palpable meaning.” In his Meskwaki grammar, in describing Meskwaki derivational morphology, Ives Goddard includes a brief discussion of a type of final Bloomfield did not take into account, namely two concrete verb finals combined into one: “Some intransitive finals are combinations of two concrete finals. In most of these the second final adds a specification of speed or mode of locomotion to the first final. In at least one case a TI final appears as a prefinal” (Goddard 2023: 199).

I propose to expand on this topic. I will further discuss the semantics — for instance, that every one of these compound word-picture stems seems to describe traversing a path. I will further discuss the morphology — for instance, the fact that there are several transitive stems of this type, as well as the intransitives cited by Goddard.

I will also discuss a few of the implications of the fact that this kind of compound verb final exists at all. Among the rest, these finals invoke a depth of imagery that we are more used to seeing in stem initials, or in stems as a whole. It seems important to note that complex finals, as well as complex initials, whole stems, and compound nouns, verbs, and particles, can evoke vivid, layered imagery of this type.

Bibliography

Early 20th-century texts by William Jones’ consultants, as interpreted by William Jones.

Early 20th -century texts authored by some 54 residents of Meskwaki Settlement in Tama, Iowa.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1946. “Algonquian”. Linguistic Structures of Native America, edited by Harry Hoijer et al., pp. 85-129. New York: Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology 6.

Goddard, Ives. 2023. A Grammar of Meskwaki. Petoskey, Michigan: Mundart Press.

Event Time: 4:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Jack Crabb is a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include morphology, language reclamation, and sociophonetics. He is a non-Indigenous Linguist.

- Monica Macaulay is the Ada Deer Professor of Language Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and is soon to step down as a co-editor of the Papers of the Algonquian Conference. She is a non-Indigenous researcher who has worked with the Menominee Tribe of Wisconsin for over 25 years.

- Vivian Nash is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and a Linguistics PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Yolanda Pushetonequa is a fourth year PhD student in Linguistics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a Meskwaki tribal member. She is interested in applying linguistic theory to practice in support of language revitalization in Native communities. Her focus includes using phonology, morphology, and syntax to inform language teaching and learning.

- Gavin Redding is a 3rd year PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research interests include linguistic change and comparative Algonquian linguistics. He identifies as non-indigenous.

Positionality statement: Two of the authors are linguists and members of federally recognized tribes. The other three authors are non-Indigenous linguists. All are at the University of Wisconsin-Madison or (in the case of the first author), recently graduated from there.

Abstract:

This paper provides a preliminary exploration of transitive psych verbs (PVs) in a set of five central Algonquian languages. PVs are “verbs which make reference to an individual being in, or getting into a certain mental state” (Hirsch 2018:1). Data was collected from dictionaries/databases of Southwestern Ojibwe, Nishnaabemwin, Meskwaki, Plains Cree, and Menominee.

Much of the literature on PVs focuses on “alternations” (Levin 1993), especially between transitives and intransitives with PP complements. Verbs in Algonquian languages do not show these types of alternations because of the centrality of transitivity to the grammar, so we focused on the internal composition of transitive experiencer subject and experiencer object verbs.

We found great diversity of initials in the two sets of verbs, but stronger patterns in the finals. For experiencer subject verbs, the most common final by far is ‘act by thought’; e.g. kwêtawêýihtam ‘s/he yearns for something’ (Plains Cree); initial kwêtaw- ‘impatiently’. In the experiencer object set, there were two finals that predominated: (1) ‘act by speech’; e.g. zegim ‘scare, frighten, intimidate, alarm him/her (verbally)’ (Southwestern Ojibwe); initial zeg- ‘fear’; (2) ‘causative’; e.g. sa͞ekehaew ‘s/he frightens, scares him, her, it’ (Menominee); initial sa͞ekeh- ‘fright’. The latter is consistent with what’s found cross-linguistically (Croft 1993:56).

We hope that recognition of these patterns will help students learn PVs more easily and could provide language programs with an approach to word formation. Future work with fluent speakers might be able to get at more subtle distinctions among the set of verbs.

References

Croft, William. 1993. Case marking and the semantics of mental verbs. In J. Pustejovsky (Ed.), Semantics and the lexicon (pp. 55-77). Dodrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hirsch, Nils. 2018. German Psych Verbs: Insights from a Decompositional Perspective. PhD dissertation. Humboldt University, Berlin.

Levin, Beth. 1993. English Verb Classes and Alternations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Venue: 4C40

Event Time: 11:30 a.m.–12:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Cherry Meyer

- Lior Cooper

- Kylie Rice

- Neomi Tehauno

- Iris Ruffing

- Teddy Shindo

Abstract:

We report findings from a study of state-level laws in the United States that mandate the inclusion of local Native histories and cultures in K-12 schooling. The US has 574 federally recognized tribes, in addition to many more who are not officially recognized. These tribes and the thousands who consider themselves tribal citizens live in every corner of the US. However, only a small fraction of states legislatively mandate that schools teach their students about local tribal history and culture with the same scope and rigor as they teach about local settler-colonial culture and history. In this project, we investigate the differing processes of creating these laws in each state, as well as the resultant legislation. This includes: the history of the relationship between tribal and state governments, the relationship between Natives and non-Natives, the events that led to the passing of the legislation, the laws’ receptions and enforcements, and the resulting effects on non-Natives’ perceptions of Natives. We then focus on Michigan, an optimal case study, as such efforts are ongoing. Through this discussion, we report on partnerships between the state Department of Education, the Indigenous Education Initiative and the Confederation of Michigan Tribal Education Departments, which lead to the development of Maawndoonganan: Anishinaabe Resource Manual, as well as the potential legislative process to implement this into state policy. The study aims to highlight the processes by which US states should include local Natives in their educational and legislative priorities through collaborative and sustainable partnerships with tribes.

Event Time: 12:00 p.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- C. Kasper

Abstract:

Across the Algonquian family we see “an articulated left-periphery for purposes of expressing the discourse function of particular arguments” (Johnson et al 2015), specifically topic and focus. In a corpus of over 6.5 hours of conversational data spoken by new speakers of Potawatomi, preverbal arguments also appear, both serving to announce new topics and to place an argument in focus. The durability of pragmatically-based word order in new speaker Potawatomi runs contra to the expectations based in the literature on contact-induced language change (Schmidt 1985, Grenoble 2019, Kantarovich 2021). It is especially remarkable since the concepts of topic and focus are not explicitly taught in Potawatomi language classes: instead, teachers and speakers describe word order by saying that the most important part of the sentence goes first. In this paper, I present data attesting to the maintenance of both topic and focus in new speaker varieties. These data bear on both word order and the functions of three discourse markers gé, yé, and the in helping mark topic and focus.

Event Time: 3:00 p.m.–3:30 p.m.

Presenters

- Dr. Keith Cunningham is a historical linguist who earned his PhD in linguistics from Georgetown University in 2024. His research focuses on the phonology and reconstruction of the Nanticoke language through colonial-era documentation and comparative work across related Algonquian languages. Dr. Karelle Hall is a cultural and linguistic anthropologist who earned her PhD from Rutgers University in 2025. Her research focuses on Nanticoke and Lenape sovereignties asserted through care-based practices and relationality. Karelle and Keith are actively working on Nanticoke language revitalization including teaching community classes, publishing a children’s language book, and collaborating with Native Roots Farm Foundation to create an Indigenous plants poster in Nanticoke and Lenape.

- Karelle Hall

Abstract

Indigenous ecological knowledge is mobilized by many Indigenous communities, including our own, to assert sovereignties and relationalities with our homelands. So often we hear about binary oppositions between Indigenous knowledge and scientific research but less about successful integrations of these methodologies. In this paper we will discuss the ways in which our work weaves together knowledge of ecologies, language, history, and all the relationships formed through these connections. We will explore how language revitalization and reconstruction work that traces the etymologies of words have helped us to deepen our relationship with plant relatives that we have become disconnected from due to the lingering impacts of colonialism. The linguistic work to reconstruct lost plant names often leads to several descriptive possibilities and the final decisions are made in conversation with community members. These community members can contribute physical knowledge about the plants themselves and their uses in community, building relationships and trust between non-Indigenous academic researchers and Indigenous researchers and Indigenous community members. Our work draws together linguists, anthropologists, storytellers, biologists, ecologists, artists, and other scholars and social and cultural activists from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. As we reconnect with plant relatives and relearn their names in our languages, we are learning more about the plants themselves, how they grow, the environments they grow in, and how they are cultivated and used by our ancestors. We are relearning practices of care that are embedded in our languages and within our plant relatives.

Event Time: 3:30 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Dr. Patricia Harms

- Dr. Serena Petrella

- Gerald Neufeld

Abstract:

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission outlined some of the most egregious impacts of colonialism and issued a clarion call for the settler population of Canada to enter into meaningful relationships with Indigenous peoples. The complex legacy of colonialism includes the forced attendance at residential schools and its legacy of inter-generational trauma, the current socio-economic crises of housing shortages, food insecurity and public education. However, buried within these generational traumas is the fundamental colonization of Indigenous histories, essentially separating communities from their collective stories. The loss of language, the change of traditional names to English, the establishment of contemporary mapmaking which erases traditional names of lakes, rivers and other significant landmarks which held cultural and spiritual significance, along with the treaty processes which effectively changed traditional leadership and political structures within communities. These profound socio-political transformations were exacerbated by the imposition of Christianity which impacted traditional marriage and clan practices.

This panel will highlight collaborations currently underway between Drs Patricia Harms and Serena Petrella with the Ansininew communities at Island Lake (this is a SSHRC funded project) and Gerald Neufeld with the Anishinaabe community at Pikangikum, Ontario. All three presenters will share the results of collaborations between the communities and the recovery of historical colonial documents as they work to de-colonize and recover traditional names, family genealogies and family systems, fur trade stories, traditional food practices along with a re-evaluation of treaty negotiations.

Event Time: 4:00 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Bri Alexander (Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation) is a Ph.D. candidate in Linguistic Anthropology at the City University of New York, Graduate Center, and has an M.A. in Native American Linguistics from the University of Arizona. Her dissertation research, funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation and Spencer Foundation, reimagines Shawnee land and language reclamation projects in Shawnee terms: as cycles of ceremonial renewal and relationality. She has also been developing language curriculum for both her tribal Nations for almost a decade. Outside of language activism, she enjoys beadworking, communing with plant kin, trying new food, and visiting with community.

Abstract:

This talking circle will ask participants to think about how their communities would define reciprocal and transitive relationships and responsibilities, particularly within their language movements and as revealed by our languages. In my language, there is an affix that denotes reciprocity and a prefix-suffix combination that denotes transitivity. Our language structure reveals that reciprocal and transitive relationships are different; the first is a relationship where all parties are working together simultaneously towards the same goal(s), whereas the latter is a relationship where each party is acting individually on or towards the other party and towards the same or different goal(s). In my context, defining these relationships is important as some language workers (e.g., community members) are naturally reciprocal while others (e.g., non-Native linguists) might be transitive. Knowing the differences can help communities set work expectations and boundaries, outline appropriate knowledge to be shared, and honor community protocols of language and cultural transmission. Participants in the talking circle will be asked to share how these concepts might emerge from their linguistic and/or cultural contexts, as well as other types of relationalities, and how these relationalities can influence the language work being done. The talking circle will close with actions to take once back in community to establish correct relationalities according to community protocols.

Venue: 4C60

Event Time: 11:30 a.m.–12:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Payton Whitehead

- Sarah Hourie

- Hope Ace

- Ashley Wacanta Daniels

Abstract:

“But it’s surprise that the generation that followed mine often turned it not to law (or social work, as both fields had prominence) but instead to towards language revitalization or to the arts when theory found the politics of recognition was failing to produce the security and space for Indigenous nations to flourish. They instead directed their energies at drawing on grounded Indigenous lifeways and a decolonial praxis that confronted and challenged to try to imagine a new future for our nations.” (Stark, p. 6)

The University of Manitoba's Indigenous Studies (IS) Department is the second oldest within the Canadian settler state. Throughout its transformative development, IS graduate students continue to encounter colonial violence that is embedded within the academy's self-sustaining structure. Dedicated to rejecting the politics of recognition (Coulthard 2014) and notions of “refusal” (Fanon 1952/2004; Simpson), IS confronts a paradigm shift: one that prompts a liberatory turn inwards, encouraging the cultivation of nation-specific Indigenous knowledges that are rooted in place-based ontologies and epistemologies to collectively practice world-building beyond the colonial present. Ushering a transdisciplinary approach to our scholarship facilitates intellectual coalitions that empower conversations surrounding the imaginings of “extraordinary possibilities” which traverse through spatial and temporal realties (Césaire, 1950/2001, p. 43). Grounded within each of our Nations distinct knowledges, we hold one another accountable through our kin responsibilities and by discerning Indigenous graduate students’ knowledge as fact to disrupt the prioritization of hierarchal western knowledge systems that have established restrictive and individualistic intellectual ideals (LaRocque 2010). This proposed roundtable aims to discuss our collective experiences as IS graduate students that (1) contributes to disciplinary knowledges of futurities (Vowel 2022) and (2) imagines other worlds that extend beyond the confines of colonial thought production. It considers meaningful approaches to building new capacities for knowledge generation that guides the present iteration of IS. By prioritizing collaboration beyond our individual research, and instead, through the development of our cohorts, we consider the impact of co-creation as scholars who have extended responsibilities to our Nations.

Event Time: 3:00 p.m.–4:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Emma Breslow

- Annika Topelian

- N. Haʻalilio Solomon

- Heather Souter

- Mskwaankwad Rice is a recent Linguistics PhD graduate of the University of Minnesota and is currently a Banting postdoctoral researcher at Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe University. He is from Waasaaksing First Nation and is a learner/new speaker of Nishnaabemwin (Ojibwe language) whose language reclamation work includes in-depth documentation of L1 speech. Claire Halpert is Associate Professor and Director of the Institute of Linguistics at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. Since 2020, she has been involved in research efforts focused on Ojibwemowin, including 2 NSF-funded projects, and works closely with the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary.

Event Time: 4:00 p.m.–4:30 p.m.

Presenters:

- Jackie Dormer

- Draco Dunphy

- Mira Kolodka

Abstract:

Indigenous language revitalization (ILR) is not simply a language learning endeavour, but a practice inextricably connected to the economic, social, health, and environmental development of Indigenous peoples. Therefore, the embodied practice of ILR cannot be fully understood through siloed, theoretically constrained fields of study. While ILR draws on knowledge that has emerged from linguistics, Indigenous education, and other disciplines, Indigenous languages cannot be exhumed from their living contexts, nor can Indigenous individuals. Pedagogical and linguistic theories have dominated the discourse on ILR, while economic dimensions have been neglected, despite funding being a key barrier for Indigenous language learners. When efforts are focused purely on learning language, they ignore the fundamental needs that influence our choices, as well as the fundamental purpose of our languages—the building blocks of our communities, our nations, our peoples, and our worlds.

Through an autoethnographic approach, the presenters will draw on their experiences as Michif and Mi’kmaw language reclaimers, respectively, to problematize the disparity between the theory and praxis of ILR. We will then propose ways ILR can flourish beyond the constraints of colonial frameworks, drawing on integrated and sustainable approaches that center Indigenous community development and nation building. We will discuss what is at risk when we use narrow, single lens approaches to ILR and what can be gained from a holistic approach. Lastly, we will provide recommendations to address this problem and move towards a path that allows for the survival of our language and the survival of our peoples.

Event Time: 4:30 p.m.–5:00 p.m.

Presenters:

- Shelley Tulloch

- Heather Souter

Registration, Breaks and Celebration

Foyer 3rd Floor

Registration begins at 8 am on Friday and the desk will be open throughout the conference.

10:30 a.m. – 10:45 a.m.

Health Break

12:30 p.m. – 1:20 p.m.

Lunch in 4th Floor Buffeteria

2:30 p.m. – 3:00 p.m.

Health Break

5:30 p.m. – 6:45 p.m.

Supper - 4th Floor Buffeteria

7:00 p.m. – 9:00 p.m.

Opening Night Celebration: Indigenous Cabaret/Variety Show in EG Hall