"Memorial Reckoning," a CRiCS and CRN event

Wed. Feb. 10, 2021

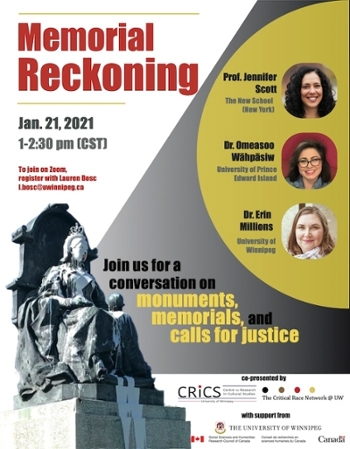

Poster for the Jan. 21 event that was co-presented by CRiCS and the CRN

Poster for the Jan. 21 event that was co-presented by CRiCS and the CRN

(Graphics: Lauren Bosc, CRiCS)

Memorials and monuments form the backdrop of our lives and attest to our history – or at least one version of that history. They have increasingly come into view and into the forefront of our minds as individuals of marginalized communities question the appropriateness of some, and how these structures vastly under/mis-represent many/most groups of people, such as women, 2SLGBTQIAA+ and people of colour. How then do we address these issues with respect to existing monuments and memorials? As we move forward, how do we ensure that memorials and monuments reflect all people in ways that are meaningful to them?

On January 21, 2021, the Centre for Research in Cultural Studies (CRiCS) and the Critical Race Network (CRN) co-presented an online event featuring Prof. Jennifer Scott (The New School), Dr. Omeasoo Wāhpāsiw (University of Prince Edward Island), and Dr. Erin Millions (University of Winnipeg). Their conversation explored the ways in which many existing monuments memorialize injustice and considered ideas for future directions.

Prof. Jennifer Scott teaches at the New School (New York) and is an anthropologist, curator, public historian, and civic leader. Scott began her presentation with a photo of Bree Newsome, a Black activist, climbing a flagpole and removing a Confederate flag in response to the massacre at a church in Charleston, South Carolina. Increasingly, Scott said, people are acting to remove monuments and symbols which are connected “with the dehumanization of marginalized people.”

Scott highlighted the importance and the role of symbols, using as an example the image of a Trump supporter holding a Confederate flag in the midst of the Capitol building during the January 6, 2021 insurrection only weeks earlier. Scott then showed a photo, also from January 6, of Jake Angeli, one of the insurrectionists, wearing a headdress, noting the brazenness of the appropriation of symbols of Indigenous culture in an attack by white supremacists.

Prof. Scott was recently appointed as Co-chair of the Advisory Committee for Chicago’s new Memorials and Monuments Assessment Project, which is working with the city’s park districts and schools to assess existing monuments. Scott said that so far, of the 500 existing monuments, 40 have been “flagged as problematic” according to a number of criteria, such as the “glorification of whiteness.” She briefly discussed ways of addressing these, such as relocating monuments or creating interventions. Scott closed her presentation by framing this juncture as an opportunity to rethink monuments in terms of their scale and size; permanence, i.e., where traditionally they have been permanent; and inclusiveness, i.e., how can they include more opportunities for participation.

Dr. Omeasoo Wāhpāsiw is a nehiyaw (Cree woman). As an assistant professor at the University of Prince Edward Island, Dr. Wāhpāsiw lives and works on the red soil of Epekwitk (Prince Edward Island, and traditional district of the Mi’kma’ki). Wāhpāsiw stated that “it’s not Indigenous to create monuments” where she views these acts as a tradition associated with colonialism. Dr. Wāhpāsiw does feel, however, there is a place for Indigenous place names, particularly ones which highlight the connection of Indigenous people to the land and to one another. Wāhpāsiw emphasized the importance of looking to the worldview of Indigenous peoples and their interpretations of the interconnections of place, space, and meaning making. Wāhpāsiw shared her interpretation of a creation story, as told by Stephen Augustine, Hereditary Chief of the Mi’kma’ki. Wāhpāsiw ended by encouraging us to consider “recreation as part of life,” saying that we shouldn’t be afraid of change and that going forward “we must create through love.”

Dr. Millions is a historian of settler colonialism, childhood, material culture, and Indigenous histories in Canada. She works at the University of Winnipeg as Director for the Manitoba Indigenous Tuberculosis Project. Dr. Millions stated that the work of incorporating Indigenous histories into Winnipeg’s landscape has been done mostly at the grassroots level. Millions shared the tragic story behind Elzéar Goulet Park in St. Boniface, as one example of this work. She explained that in 1870 in the wake of the Red River Resistance, the Métis people protested the sale of Rupert’s Land without consultation. Colonel Wolseley arrived with troops at the settlement that would become Winnipeg in order to oversee the transition of power which would make way for colonial settlers. Millions said that this time in our history is remembered as the “reign of terror.” She went on to explain how it was that Wolseley’s men chased Elzéar Goulet, a Métis leader, and forced him into the Assiniboine River. Goulet attempted to swim to the other side of the river, but sadly drowned. The park, she said, was established where Elzéar Goulet would have landed, if he’d been successful in crossing.

Millions explained that prior to 1870, 88% of the settlement’s inhabitants were Métis, but that the population shifted dramatically in the next 40 years with colonial settlement. Many of Wolseley’s men settled here. According to Millions, “remembered as the victors,” theirs is the history that has been inscribed in the memorials in our city and in the naming of our parks, streets, and schools. Still, she said, “a small persistent population of Métis people” remained here. And, in spite of attempts to erase the city’s Indigenous heritage, Millions stated that “the Métis didn’t forget their history.” Elzéar Goulet Park is but one example of this.

Dr. Millions serves on the Welcoming Winnipeg Committee of Community Members. The Committee, she says, seeks to address the erasure of Indigenous history and the visible absence of Indigenous perspectives in the city’s monuments and street names. The Committee will hear all applications concerning memorials and the naming/renaming of streets in the city. The Committee is currently establishing the application process, one which Millions said, will be a departure from the usual municipal conventions, incorporating Indigenous perspectives. The Committee, she said, which was struck in August 2020, has already determined that two principles will guide their work. First of all, decisions made by the Committee should (i) make Indigenous peoples feel safe and comfortable in their own lands, and (ii) reclaim land and space as well as incorporate Indigenous languages into Winnipeg’s urban landscape.

I want to note that an Indigenous land acknowledgment - and water - was done at the beginning of the event. This is important to state whenever we gather, but particularly so in the context of a conversation about monuments and memorials for the way in which these structures mark and are imposed upon territory and the land(scape), as noted by CRiCS Director Dr. Angela Failler in her acknowledgment. The University of Winnipeg is located in Treaty 1 territory, and the land is “the traditional territory of the Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, Dene Peoples, and the homeland of the Métis nation.”

Each of the speakers also gave a land acknowledgment as they were introduced:

- Prof. Jennifer Scott (present day Chicago, IL) acknowledged the “original homelands of the Ojibwe, the Odawa, and the Potawami nations.”

- Dr. Omeasoo Wāhpāsiw (living and working Charlottetown, PE) acknowledged the Mi’kma’ki people.

- Dr. Erin Millions (St. Boniface) acknowledged the Métis, as in her presentation.

And, finally, in closing, I want to thank Dr. Angela Failler, Director of CRiCS, and Dr. Jenny Heijun Wills, Director of the CRN, for bringing us together for such an important discussion on a topic that is so timely and relevant to our UWinnipeg community and beyond. I appreciate not only the effort that went into coordinating an event of this scale, but also that it was done in a considered and thoughtful way. Thanks as well to Lauren Bosc, Research Coordinator for CRiCS, for providing her support to the event and to Kate Pettigrew for providing the Close Captioning.

More than 100 people registered for the event from 20 different countries, making it all the more impactful and one which could have – literally – far-reaching implications. The success of the event speaks to the sense of urgency we collectively feel concerning the need to keep research engagement happening at all times - even amid the pandemic.

Lisa McLean

Faculty of Arts

See also:

Memorial Reckoning - This page on the Centre for Research in Cultural Studies (CRiCS) website features information about the event as well as a recording of the event.